UNDONE: Johnny Depp, Debra Winger and Marlon Brando were to have starred in the film.

BARRY NAVIDI IS STILL TRYING to figure out just what happened. Last July he was on location in Ballycotton, Ireland, making a $13-million movie—modest by Hollywood standards but impressive for a fledgling producer from London, especially since it starred Marlon Brando and Debra Winger and had Johnny Depp and John Hurt in supporting roles. A month later he was hoofing it in Beverly Hills—no hotel suite, staying with a friend, having lost his home, his money, his partner’s money, his partner’s father’s money, an outside backer’s money and seven years of work on a picture that folded after two weeks of shooting.

That’s $2.85 million with nothing to show for it but 29 minutes of film in a closet in his rented flat in North London—29 minutes of film and the knowledge that, for a while at least, he’d marshaled the incredible array of forces required to produce a major motion picture. Before he got the phone call from Los Angeles. Before his backers disappeared. Before the promises they’d made dissolved into a dizzying maze of claim and counterclaim only the lawyers can untangle.

“If I’d gone to a casino,” he says ruefully, sipping black coffee outside a Beverly Hills patisserie, “at least I would have enjoyed it.”

Solidly built, with olive skin and salt-and-pepper hair in a modish cut, Navidi is one of thousands of filmmakers and filmmaker wannabes who have come to Los Angeles, lured from Spain or Italy or France or Israel by the romance and the market potential of Hollywood. He fell in love with the movies as a small boy in Iran, when he would sit in front of the movie screen in his parents’ house for hours and lose himself in Hollywood make-believe. As a vice president of the National Iranian Oil Co., his father could arrange for private screenings of all the latest releases. The first one Navidi remembers is The Sound of Music, with Julie Andrews yodeling Rodgers & Hammerstein through the Austrian Alps. After that came sterner stuff—Kelly’s Heroes, Where Eagles Dare. Then he was sent to boarding school in England, and when he asked to go to film school after graduation, his father didn’t object. Which is why, at 35, Navidi is in Beverly Hills right now.

Solidly built, with olive skin and salt-and-pepper hair in a modish cut, Navidi is one of thousands of filmmakers and filmmaker wannabes who have come to Los Angeles, lured from Spain or Italy or France or Israel by the romance and the market potential of Hollywood. He fell in love with the movies as a small boy in Iran, when he would sit in front of the movie screen in his parents’ house for hours and lose himself in Hollywood make-believe. As a vice president of the National Iranian Oil Co., his father could arrange for private screenings of all the latest releases. The first one Navidi remembers is The Sound of Music, with Julie Andrews yodeling Rodgers & Hammerstein through the Austrian Alps. After that came sterner stuff—Kelly’s Heroes, Where Eagles Dare. Then he was sent to boarding school in England, and when he asked to go to film school after graduation, his father didn’t object. Which is why, at 35, Navidi is in Beverly Hills right now.

There’s nothing new about Hollywood’s appeal to foreign filmmakers: Hitchcock succumbed in 1939. But as European cinema has languished, the victim of rising costs and tightened funds and a language barrier that shackles its commercial potential, people like Navidi find themselves with fewer and fewer options.

In the meantime, paradoxically, a worldwide boom in multiplex theaters and cable and satellite TV has led the Hollywood studios to look overseas more and more for their profits. The combination has put Hollywood at the vortex of a global entertainment industry, with cash and talent funneled in from all quarters but everyone playing by Hollywood’s rules. The Divine Rapture story shows what can happen to a picture that challenges those rules—that flouts studio conventions for the uncertainties of high-wire financing.

Divine Rapture was to have been Navidi’s first feature film, a black comedy about a young woman who seemingly rises from the dead, only to be seized upon by an elderly priest who needs a miracle to redeem his faith. The script was quirky, trafficking in taboos (death, religion) that made it off-limits to the major studios.

But with the film a low-budget, independent production, those same qualities gave it the makings of a left-field hit—something on the order of The Crying Game or Driving Miss Daisy, neither of which had been viewed as having much box-office potential when they were in development. A long shot, to be sure—but in this business, what isn’t?

THE TRADE-OFF FOR FREEDOM from second-guessing by studio executives is a scramble to secure independent financing. The standard route is to lock in a North American distribution deal, sell off foreign rights—territory by territory—and take the whole package to a bank, which will use the distribution guarantees to secure a loan to cover the cost of production. There’s plenty of room for disaster, but once the cameras start rolling on a picture with major stars, it’s highly unusual for the picture to collapse.

“This is something I’ve never heard of happening,” says Ed Limato, Brando’s agent, in his corner office at International Creative Management. “I’ve heard of problems, grave problems, at the last minute but always something fixable. This is extraordinary.”

Navidi had a deal with a Paris-based company known as CineFin, which had a domestic distribution agreement with Orion Pictures, the troubled studio controlled by billionaire John Kluge. CineFin, headed by an international entertainment lawyer named David Lowe, was supposed to provide Orion with four or more pictures a year for three years and the money to market them, a total commitment of some $600 million. But announcements of the CineFin-Orion deal had failed to mention where the money was coming from, just as they failed to mention two other principals in the firm: Frederick and Richard Greenberg, sharp operators whose previous venture, a satellite-broadcasting company known as SkyPix, had just gone down in flames with a loss of some $45 million, including $10 million from Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen.

“Maybe there was a reason for this not to happen,” Navidi says, grasping for some cosmic explanation. His voice has the precise tones of an English schooling, but his costume—blue jeans and blue denim shirt, freshly pressed, with cowboy boots and western belt—is pure Hollywood. “Seriously. Because I don’t know why it didn’t happen.”

But he does know, of course. And the question he keeps asking is: When should he have figured it out? In Los Angeles last March, when, unable even with Brando attached to get backing from the Hollywood studios, he signed a deal with CineFin that seemed almost too good to be true? In April, when he and his partner agreed to fund pre-production themselves—eight to 10 weeks of scouting locations, building sets, hiring a crew—while CineFin arranged its bank financing? In May, when they agreed to defer their $500,000 producers’ fee so CineFin could make the budget work? In June, when they decided to start shooting July 10 without the bank loan in place because some final paperwork remained to be done and they’d lose Brando if they delayed? The week of July 10, when CineFin’s money failed to materialize and they started talking with an outside investor as the cameras rolled? The week of July 17, when Navidi mortgaged his house to keep the production going a few more days while the outside investor went through CineFin’s books?

“It’s a point of no return,” Navidi says. “And when you’re cornered and you’re on location, it’s like it’s your baby and there’s nothing you wouldn’t do to save it.”

But Navidi wasn’t the only one who tried too hard to save this picture. Divine Rapture went so far on so little because it held out some special promise to everyone involved: Navidi had never produced a feature film, director Thom Eberhardt had been stuck making formula comedies for Walt Disney, screenwriter Glenda Ganis had never had a film script produced, Debra Winger and Johnny Depp were eager to work with Brando, CineFin hadn’t launched a single project a year after announcing the Orion pact, and Orion needed product to fill its distribution pipeline as the company emerged from bankruptcy.

“Everybody was projecting their own needs onto this movie,” says a knowledgeable Hollywood source. “It’s always like that, of course. It’s just that this one was a particularly strange convergence.”

CINEFIN’S OFFICES ARE ABANDONED NOW, an empty warren behind an unmarked wooden door on the sixth floor of Orion’s sleek high-rise in Century City. Odd pieces of telephone equipment and months-old trade papers are scattered about, pictures have been ripped from the walls. Virtually the only thing left intact is a Rodney Dangerfield poster in the reception area, his screwball face peering out wildly across the room. Easy Money, the poster proclaims. The fine print reads, “Copyright Easy Money Associates—a Greenberg Brothers Partnership.”

The Greenberg brothers, Fred and Richard, go back a long way with Orion. In the early ’80s, shortly after Orion was formed, the Greenbergs provided P&A money—prints and advertising, the ante it takes to market a film—for a number of Orion pictures. Some, like Easy Money, were made by Orion itself; others, like The Terminator, the low-budget 1984 sci-fi epic that made Arnold Schwarzenegger a superstar, were made by Hemdale Film Corp., a high-flying independent that distributed its pictures through Orion.

“Maybe there was a reason for this not to happen,” Barry Navidi laments.

It was easy money to raise: Not only are P&A funds “last in, first out,” in industry parlance, but federal law allowed investors to take steep tax deductions. Even after Congress eliminated such tax shelters in 1986, the Greenbergs were able to sell limited partnerships investing in films, in real estate, even in a Massachusetts car dealership. One of their prime sources of cash was a small but well-connected brokerage firm in Seattle.

During the ’80s, while the Greenbergs were funneling hundreds of millions of dollars to Orion and Hemdale and similar companies, CineFin’s future president, David Lowe, served as Hemdale’s outside counsel. Lowe, then based in London, was a charmingly international man who spoke fluent French and maintained a villa in the south of France. He also had a reputation as a ferocious negotiator who had put together enormous deals involving such companies as Credit du Nord, the French pay-TV company Canal + and, of course, Hemdale.

But behind Hemdale’s impressive slate of films lay an operation that was questionable at best. In July 1992, the company was sued by the Screen Actors Guild and the Directors Guild of America for allegedly failing to pay residuals on 27 of its films; two months later, it was forced into bankruptcy by angry creditors, among them Lowe himself, who claimed debts of nearly $600,000. None of these suits has yet been resolved.

THE GREENBERG BROTHERS WERE HAVING THEIR OWN PROBLEMS. In 1989, federal authorities had shut down a New York bank they owned amid charges that it had made improper loans to partnerships the Greenbergs controlled. Two years later, the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which oversees nationally chartered banks, had barred them from the banking industry after concluding that they had reaped some $2.28 million in a series of illegal transactions. By 1992, they were in hot water in Seattle, where reports of a New York grand jury probe into their banking activities were hindering their ability to launch SkyPix—even though no indictments were ever issued.

Using an advanced digital compression technology licensed from a Silicon Valley start-up, SkyPix had planned to sell receiver sets at $1,000 apiece and beam down programming on a pay-per-view basis. But the launch was months behind schedule, and with their investors being subpoenaed, their assets frozen by the courts and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. suing them for $1.8 million allegedly owed to the Bank of New England, the Greenbergs were in no position to beam anything to anybody.

In the spring of 1992, as they grappled for control of the company with Allen, the billionaire Microsoft magnate, the cash crunch cost them all but one of the 10 Hughes satellite transponders they’d leased. The Securities and Exchange Commission launched its own investigation in June as lawsuits from former employees and business partners mounted.

The Greenbergs were unbowed: “We’re going to launch the system,” Richard Greenberg told Forbes defiantly, “we’re going to launch it correctly, and then we’re going to sit back and watch the 21st century unfold.” Two months later, a federal judge declared SkyPix bankrupt.

BACK IN LOS ANGELES, ORION WAS having problems as well. Despite its success with Dances with Wolves and The Silence of the Lambs, the studio had hit the same wall that shattered Hemdale and other independents in the early ’90s—rising production costs coupled with faltering sales in the home video and TV syndication markets. Orion filed for bankruptcy protection in December 1991, and with its top executives gone, Leonard White, who had headed its home video subsidiary, was named president. It was barred under the terms of its reorganization plan from going back into production, but it held onto its distribution operation and its library—some 750 films, including such prizes as the Kevin Costner hit Bull Durham, Oliver Stone’s Platoon and Salvador, Milos Forman’s Amadeus and Woody Allen pictures like Broadway Danny Rose The Purple Rose of Cairo.

Meanwhile, in London, Lowe had tired of putting together deals for other people and decided to do something for himself—like buy a film library, perhaps, and use it as collateral to launch his own production studio. Through Mark Crowdy, a well-connected London actor who was likewise interested in producing, he met with English bankers and pitched them on a plan to acquire the Hemdale catalog. Hemdale wanted too much, so Lowe moved to Paris, set up offices on the rue de Rivoli, and started a lucrative business arranging international financing for French filmmakers. But his ambition to run a studio didn’t die.

Early in 1994 he emerged as president of CineFin, a loan syndicate that was being run out of the Greenbergs’ headquarters in a down-at-the-heels Manhattan office building, a cavernous loft filled with unused partners’ desks from their failed bank. Shortly afterward, with backing from Smith Barney Shearson and Oppenheimer & Co., CineFin made a bid to buy Orion. Those discussions ended when the banking consortium collapsed a few months later, but CineFin soon made another deal—two deals, actually.

The first, announced in July 1994, was the $600-million agreement to finance pictures for Orion—the money, according to Lowe, to come from financing institutions and rich investors lined up by the Greenbergs. The quid pro quo, announced two months later, was an understanding that allowed CineFin to sell Orion’s films—its existing catalog as well as future releases—overseas.

ONE MAY WONDER WHY ORION, a reputable if troubled company controlled by one of the richest men in America, would hand over its crown jewels to the Greenbergs. Orion doesn’t see it that way.

“It seemed like a wonderful way to pick up some pictures and keep our operation fed,” says Len White, a portly man flanked by aides. “It was a completely risk-free situation from the company’s standpoint.”

In the words of one Hollywood executive: “If you only did business with people who were pure in this town, you’d never make another movie.”

But could CineFin deliver? Some had their doubts. Peter Bart, editorial director of Variety, had lunch with White shortly before the deal was announced and was told that Lowe would be financing a slate of pictures. Incredulous, he went back to his office and had his assistant track down Lowe.

As Bart tells it, they found him on a yacht on the Riviera. It was close to midnight, but a party was evidently in progress; Bart could hear laughter and music and glasses clinking in the background. Was it true that CineFin was going to come up with $200 million a year for three years to finance these pictures? Lowe laughed and asked where he’d gotten that number. In the press release you’re sending out, Bart replied. Was it true?

“Whatever it says,” Lowe is said to have responded, laughing as if someone had just told him the funniest joke of his life.

Six months later, CineFin still had not demonstrated to Orion’s satisfaction its ability to fund a picture. It was reportedly in danger of defaulting on the deal when Mark Crowdy, who divides his time between a garden flat off King’s Road in Chelsea and a house in Benedict Canyon, phoned Lowe with an idea: Barry Navidi’s Divine Rapture.

Next: How Barry Navidi attracted top-flight talent to “Divine Rapture,” only to discover that CineFin was a house of cards.

As the Escrow Flies

There’s more room than ever in the film business for wannabe players. Just ask the people involved with last summer’s aborted feature “Divine Rapture”

December 24, 1995 | Second of two parts

Last week, we reported how Orion Pictures, unable to finance its own slate of films, turned to a film-financing company known as CineFin, two of whose principals, Fred and Richard Greenberg, had been booted out of the banking industry by federal regulators. This week, how producer Barry Navidi’s dream—”Divine Rapture”—came undone in July 1995. The full truth may yet come out in litigation.

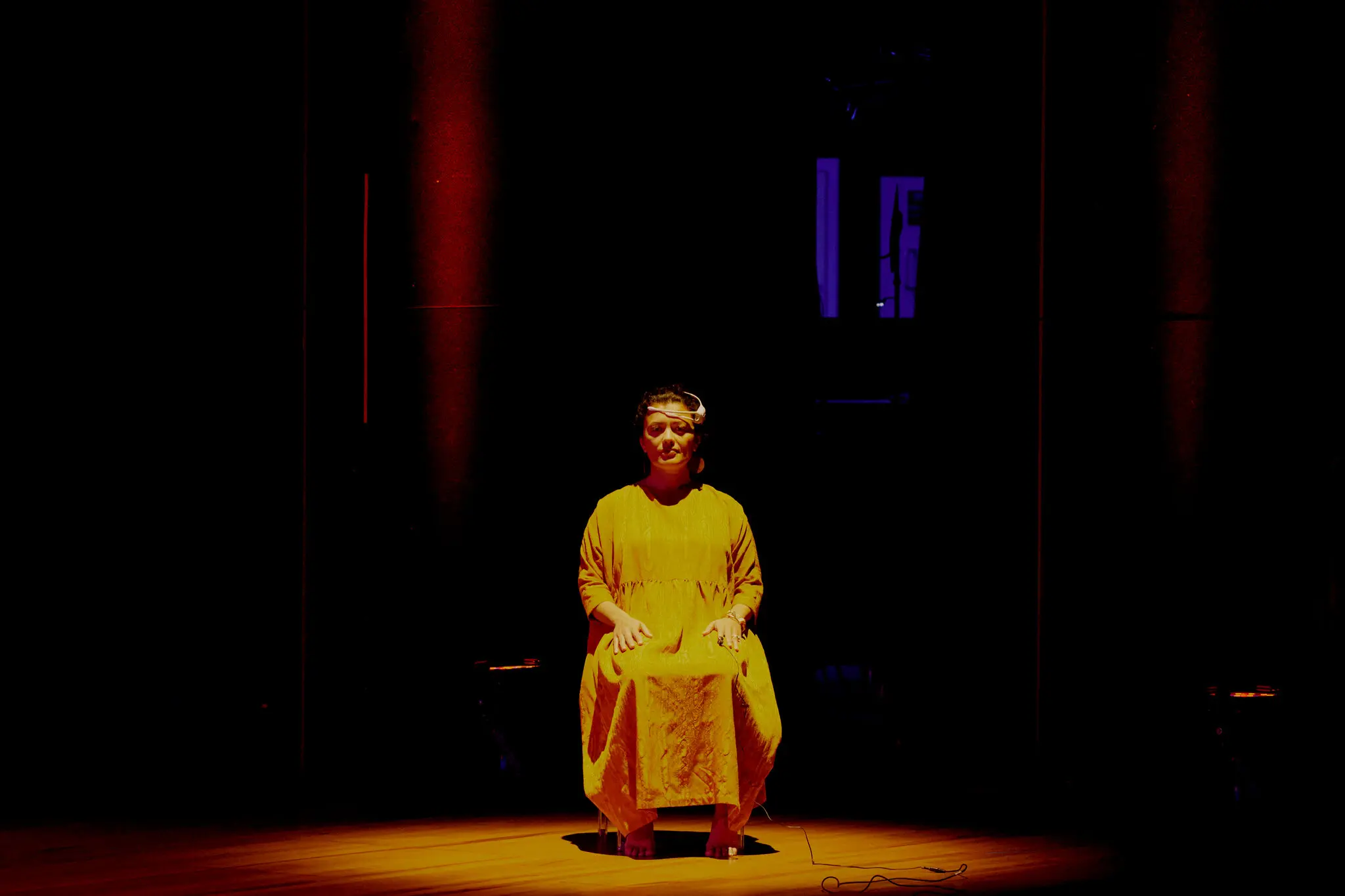

Marlon Brando and Johnny Depp enjoy a laugh in Ballycotton, Ireland—before their paychecks failed to arrive.

DIVINE RAPTURE HAD ITS GENESIS nearly 20 years ago, when Glenda Ganis saw an item in the Los Angeles Times about a Sicilian woman who’d died and come back to life 12 hours later. The woman hadn’t really died, it turned out; she had catalepsy, a psychological disorder that makes the muscles go rigid and the body completely non-responsive. Ganis, who was married to veteran Hollywood studio executive Sid Ganis and working as a production designer, saw the whole story in a flash: A woman in a remote fishing village in a Catholic country goes cataleptic and wakes up as if by miracle. She wrote a 26-page outline and put it aside. Ten years later, she met an Italian producer who talked her into writing it up as a script. The title was Mamma Mia.

The producer disappeared and Mamma Mia gathered dust until 1987, when Ganis’s former agent showed it to Barry Navidi. Navidi, fresh out of film school, had made one picture—an hourlong drama titled Mrs. Corbett’s Ghost, starring John Huston and directed by his son Danny, with financing from John Paul Getty III. “I liked him,” says Ganis, a compact woman with reddish-brown hair in a Shirley MacLaine do. “He was young, eager, enthusiastic, sweet.” She changed the title to Divine Rapture, and Navidi and his partner—a film-school classmate named Damien Burger whose father, a Swiss cigar magnate, provided their development money—tried to set it up.

In earlier years, they need barely have ventured past London. But shortsighted tax policy and overcautious banking practices had so hobbled the British film industry that the only sure way to finance a picture there was through credit cards. Pinewood, the once-great home of the Rank Organisation, was nothing but a four-walls studio, its soundstages rented out to the highest bidder. Twickenham, when Navidi and Burger had their offices, was mostly given over to television production, and Boreham Wood, the legendary MGM studio in Hertfordshire, was now a distribution center for a deep-freeze company. Navidi and Burger would have to go elsewhere.

At first they hoped to shoot it in Italy, with Isabella Rossellini and Ben Kingsley in the lead roles and a budget in the $5-million range. Kingsley dropped out and Ron Silver dropped in. Their Italian investors dropped out because Navidi wouldn’t make it in Italian. Telly Savalas wanted to star, but only if he could move it to Greece. Richard Lester urged them to move it to Ireland—a hot country after The Crying Game, with a government-sponsored fund ready to put in 20% of the budget.

Four rewrites later, with Miranda Richardson and Albert Finney attached, Navidi went shopping for a deal in Hollywood. The studios expressed interest but didn’t bite. A private investor was set to finance it but pulled out at the last minute. In the summer of 1994, with the Irish weather too unpredictable to allow shooting until spring, the project was shelved for another year.

That fall Navidi’s agent, Dennis Selinger of International Creative Management, invited him to a dinner party at the Ivy, a clubby West End restaurant that’s popular with London’s theater set. Navidi found himself chatting away with Belinda Frixou, Marlon Brando’s attorney. A few days later, she phoned him to say that Brando was interested in playing Father Fennell, the priest who witnesses the miracle. He sent her the script, and one morning last November Brando rang him up at home and told him he wanted to do it. For Navidi, it was a peak moment.

WITH BRANDO ON BOARD, the picture Navidi had been unable to set up at $5 million suddenly ballooned into a $10-million production. Still, Navidi was on a roll. By early January, Debra Winger had committed to play Mary, the woman who dies, and Navidi’s friends were asking how he’d done it. But he still lacked financing, and when he got to Los Angeles he discovered that having Brando and Winger attached was not necessarily a plus.

He was told that Brando was difficult to work with, that Winger was a notorious troublemaker. Meanwhile, Frixou wanted a quarter of Brando’s $4-million salary put into escrow immediately. Navidi had been making the rounds, but half the studios said no and the rest were in no hurry to decide. He felt like he had a gun to his head. He called Mark Crowdy, an actor he’d met in London.

Crowdy was in Beverly Hills when Navidi called, and he had just the person to talk to—his old friend David Lowe, now president of CineFin. That Friday the three of them met at CineFin’s offices in Orion’s Century City headquarters, and on Tuesday Navidi went back to sign a contract. There he met a David Williams, who was supposed to provide the prints and advertising funds, and Fred and Richard Greenberg, who were introduced as consultants. Unknown to Navidi, the Greenbergs had been in trouble with federal authorities since 1989 for banking improprieties and were barred from the banking industry in 1991.

“I had no idea who they were or what their background was,” he says now. “I was incredibly happy.”

The deal called for profits to be split 50-50 between CineFin and Touchwood Films, Navidi’s partnership with Damien Burger. Orion would provide North American distribution, CineFin would provide all financing and handle foreign sales, and Touchwood would arrange for a completion bond—insurance in case the production went over-budget—and deliver the finished picture. But a snag developed almost immediately: Brando’s escrow. CineFin was prepared to put up only the standard 10% on signing—$400,000, instead of the $1 million the actor wanted.

This time, Crowdy rang up Kristi Prenn, widow of electronics entrepreneur Daniel Prenn and one of the wealthiest women in Britain—or not in Britain, since she’d exiled herself to Monaco. Prenn had never invested in a film before, but she was going to London for a charity ball and she agreed to meet Lowe at his flat in South Kensington. Forty-eight hours later, she agreed to put up the full $1 million for Brando and $100,000 for Johnny Depp, repayable on the first day of principal photography. Her profits would be split between a clinic in India she supports and an Indian village that needed wells and a sewer system.

Prenn, a woman of many enthusiasms, set out to make Divine Rapture a household word. She persuaded the Harkness Nurseries, one of England’s finest, to name a new rose after the film. She arranged for a foal to be named Divine Rapture as well, sired by Pursuit of Love out of Pillowing.

Meanwhile, Navidi and Burger and Thom Eberhardt, a journeyman director whom they’d hired on the basis of the Sherlock Holmes spoof Without a Clue, went to Ireland to scout locations. They settled on Ballycotton, an old but none-too-quaint fishing village in County Cork, and hired a crew to build sets.

Yet even now, the odds were against them. “I had my doubts it would happen,” says Brando’s agent, Ed Limato. When Brando’s daughter Cheyenne committed suicide in April and Brando went into seclusion, nearly everyone wrote the project off. Only Navidi continued to believe.

“We were naive,” admits Barry Navidi

“Barry was unsinkable,” recalls Thom Eberhardt, lounging by the pool behind his storybook fieldstone house in Glendale. “I’d never met somebody so full of can-do spirit with nothing to base it on. He wanted this picture to happen more than anything else in the world.”

But Eberhardt was eager as well. He saw the picture as Capraesque, a fable about miracles and faith and belief in oneself, and he bought into it against his better judgment.

“Everybody wants you to be passionate,” he declares as he heads into the kitchen for a beer. “You’ve got to want to do this more than anything in the world. That’s how you continually get beat up, when you allow yourself to get worked up over something. But this project—I was getting very excited about it.”

THE WILLINGNESS TO BELIEVE: That’s what Divine Rapture was all about. The story opens with Mary (Debra Winger), frustrated with her marriage and her dead-end job in a lingerie factory, apparently dying while making love to her husband. He doesn’t notice. When she revives during her wake, Father Fennell (Marlon Brando) proclaims it a miracle. She produces more miracles on demand, rejecting the factory-owner’s plea for an endorsement (“Saints don’t endorse bras and girdles”) and embarking on a purification ritual of fasting, celibacy and jogging. Finally, she collapses a second time outside the parish church—only to have the village doctor (John Hurt) revive her with a bucket of cold water—as an angel seems to appear overhead.

To the people of Ballycotton—where the high point of most summers is the annual cow-pat competition, in which a cow is put in a field marked off in squares and people bet on where it will let loose—the arrival of an English film crew and several Hollywood movie stars was itself something of a miracle. To the Irish papers, it was front-page news; for the Ministry of Arts and Culture in Dublin, it was the latest vindication of a tax policy which had led to the completion of 20 films in Ireland the year before. But while Divine Rapture promised to pump some $4 million into the local economy, CineFin had yet to start funding it.

Navidi and Burger were hired producers now, yet CineFin’s requests that they defer their fee and keep financing the production struck them as plausible. The company’s financials looked healthy, and if the two most powerful agencies in Hollywood—Creative Artists Agency, which represents Winger, and ICM, which handles Depp, Brando and Navidi—thought it was OK, what did they have to worry about?

In fact, both CAA and ICM seem to have had their doubts. But the standard approach when negotiating star contracts with unproven production outfits is to get the salary put into escrow, and that’s what both agencies did.

Brando’s attorney insisted on using Brando’s own escrow company, and Depp was taking so little for the privilege of working with Brando that escrow was beside the point. But CineFin agreed to put up the money for Debra Winger and for Thom Eberhardt, provided they use CineFin’s escrow company—Capital Crest Financial Escrow Management, headed by one Roger Mathews and located at 3900 Alameda Ave., 17th floor, Burbank.

“Everybody wants you to be passionate. You’ve got to want to do this more than anything in the world. That’s how you continually get beat up, when you allow yourself to get worked up over something. But this project—I was getting very excited about it.” —Thom Eberhardt, director

The building at 3900 Alameda Ave. is a sparkling new high-rise just around the corner from the Warner Bros. lot. Its prime tenant is the Walt Disney Co., but the 17th floor is used as a mail drop by less-established enterprises; in business lingo, it’s a parking lot. As for Capital Crest, it had been registered with the Los Angeles County Clerk’s Office in June 1994 as a fictitious business name for J. David Williams, chief operating officer of CineFin and the man responsible for raising the escrow funds.

In May, Brando emerged from seclusion to say that he was going to make the picture after all. With pre-production well underway in Ballycotton and three other films in the works, CineFin made a splashy debut at Cannes. But while David Lowe made a concerted—some later said desperate—effort to sell foreign rights, the major territories went unsold.

THE NEXT STEP FOR CINEFIN was to get a bank loan and start cash-flowing the picture as promised. CineFin had made funding arrangements with FILMS, a London firm that packages loans for Berliner Bank in Germany. Because the pre-sales hadn’t gone well, however, Lowe asked for a guarantee from Orion, which had agreed to pay 20% of the production budget for North American video rights. Unfortunately, Orion was just emerging from bankruptcy, so its paper wasn’t fully bankable. They could get a guarantee from Metromedia, Orion’s major shareholder—but Orion refused to go to Metromedia until CineFin showed itself capable of funding the picture. CineFin was missing a critical piece of the jigsaw puzzle, and without it neither the bank loan nor the completion bond could move forward.

“This is the stage at which I was getting hysterical,” says David Lowe, speaking by phone from his offices in Paris. “I was saying to the Greenbergs, ‘Where are all these supposed investors? We need some equity! You’ve been promising it—where is it?’ Then I came to the conclusion that there were no investors—that they were probably figments of the Greenbergs’ imagination.” (The Greenbergs did not return phone calls for this article.)

Alarm bells were sounding in London and Beverly Hills as well.

“I said, ‘I don’t see how you can start shooting without a completion bond,’ ” says Dennis Selinger of ICM. “But David Lowe kept saying that it was going to be all right, that it was just a question of getting Orion to sign some bits of paper. And I don’t think anything in the world would have made Barry think it wasn’t going to go.”

At this point, Navidi and Burger had already invested $500,000 in pre-production, most of it from Burger’s father. Brando was set to fly to Australia in August to star in The Island of Dr. Moreau. And statements from the Bank of America showed the escrow accounts to be in order; why would CineFin risk all that money? So the cameras rolled on July 10, even though FILMS had not yet gotten the paper it needed to begin due diligence on the loan, even though Film Finances, the company that was to supply the completion bond, had yet to receive its fee. The entire production was proceeding on faith.

THE FIRST WEEK OF PRODUCTION WAS HEADY and chaotic. Brando moved into a 12-room Georgian mansion at $4,800 a week while its owner lived in a trailer on the grounds. It rained every day. Navidi looked around and thought, I’ve done it! But no money was forthcoming from CineFin—not for the cast, not for the crew, not for their suppliers, not for the townspeople who were giving them bed and board and turning over their shops and fishing boats for the shoot.

When Kristi Prenn showed up with a basketful of Divine Rapture roses and Navidi suggested that she take over the production, she seemed interested. When David Lowe arrived, he seemed interested as well. That’s when Navidi got really worried. While the producers huddled with Lowe and Prenn in a smoke-filled room in the Bayview Hotel in the center of town, Thom Eberhardt tried to ignore the rumors and shoot the movie.

At the end of the week, Winger told Navidi that she knew he had financial problems but she wasn’t going to back out—even though she hadn’t been paid. Navidi was stunned: Winger should have gotten $250,000 from her escrow account with Capital Crest the day they started shooting.

When Brando’s second $1-million paycheck failed to arrive on Monday, it was clear there were real problems. Navidi summoned the cast and crew and announced that they were temporarily suspending production. Jeff Berg, ICM’s chairman, swung into action in Los Angeles, working furiously to close the breach between CineFin and Orion. Winger and Hurt spoke with Brando, and by Tuesday evening he’d agreed to go back to work while the financing was straightened out.

By now it was obvious that CineFin wouldn’t be able to finish the picture. But with the cast they’d assembled and the footage they had in the can, it seemed inconceivable that someone else wouldn’t pick them up. Kristi Prenn seemed eager to step in with bridge financing, and talks were underway with Miramax and New Line Cinema. Confident they’d have a deal within a week, Navidi mortgaged his London flat and used the money to keep them going.

Lowe left for London. Prenn was holed up in the Bayview Hotel with her advisors.

A few days later, a fax arrived from Los Angeles: Orion had issued a quit claim, giving up its rights to the property. Prenn held it up triumphant. Gentlemen, she cried, we have a picture!

Navidi was still elated when he was awakened by a phone call early the next morning. It was Rick Nicita of CAA. Winger’s attorney, Barry Hirsch, was on the line as well. It was Friday evening, Pacific time.

Nicita declined to comment for this story. But as Navidi recalls it, the first thing Nicita said was, Barry, you know Debra hasn’t been paid. Then he said to Hirsch, Barry Navidi is the victim in all this.

What’s going on? Navidi wanted to know.

Nicita was blunt: There is no escrow company. There is no escrow account. There is no money.

Navidi was stunned. What? Am I in a nightmare?

“I felt like somebody had pushed me from an airplane at 30,000 feet without a parachute,” Navidi says now.

“THE NEAT THING,” SAYS DAVID WILLIAMS over lunch in Beverly Hills, “would be for everybody involved in this picture to get their money back.” Williams is propriety personified, an impeccably groomed young man in a somber double-breasted suit and a starched white shirt with monogrammed cuffs. Aside from Orion, whose delays he says caused the bulk of the problem, he blames the collapse of the film on Roger Mathews, the elusive president of Capital Crest. “When the film fell apart,” Williams says, “he said we’d breached an agreement with him and pulled all his funds and literally disappeared.”

Stephen Marks can attest to that. Marks is an attorney for Brownstone Financial, a West Los Angeles lending institution that filed suit against CineFin and Williams in September, alleging that it had put up more than $1 million in escrow funds for “Divine Rapture” and three other CineFin projects and that the money had never been returned. And as for Roger Mathews—”Is there such a person?” Marks asks. “I don’t know. I can only tell you that according to Mr. Williams, Mr. Mathews has disappeared off the face of the Earth.”

“The story I was told,” says David Lowe, “is that the escrow company—what was supposedly an escrow company, Capital Crest, which was in negotiations with David Williams, with which he said he’d done business before—said to him, ‘This is a great business, we want some of it. If your people put up part of the escrow, we’ll put up the rest.’ But . . . the end of the first week came and the drawdown was called for and we still had not been funded via the banks. . . .”

Lowe says that he’s never met Roger Mathews either.

Unfortunately for Navidi, the discovery that the escrow accounts were not funded had an immediate and electrifying effect in Ballycotton.

“When something like that happens,” says Crowdy, “everybody starts running.” Kristi Prenn, Miramax, New Line—suddenly, it was as if the room had cleared and gusts of wind were blowing through the open windows.

December 17, 1995

December 17, 1995