Professional success was not among the favored values of the late 1960s; it was a time when idealism was the bottom line. Now, some fifteen years later, social conscience has given way to social Darwinism. Those who joined together to fight the system have now joined the system to fight for success. In a crowded marketplace not everyone can win, but entrepreneur and engineer T. J. Rodgers is one who won’t easily lose.

IT WAS 6:42 A.M. ON THE LAST MONDAY in September when T. J. Rodgers pulled into the lot at Cypress Semiconductor. This was day one of workweek thirty-nine, the final week of the quarter—a week when the whole company would have to bust ass to meet its projected revenue goal. The eighteen-month-old concern was only in its third quarter of production, and this quarter’s goal was triple that of the one before. T.J.’s job was to make it happen.

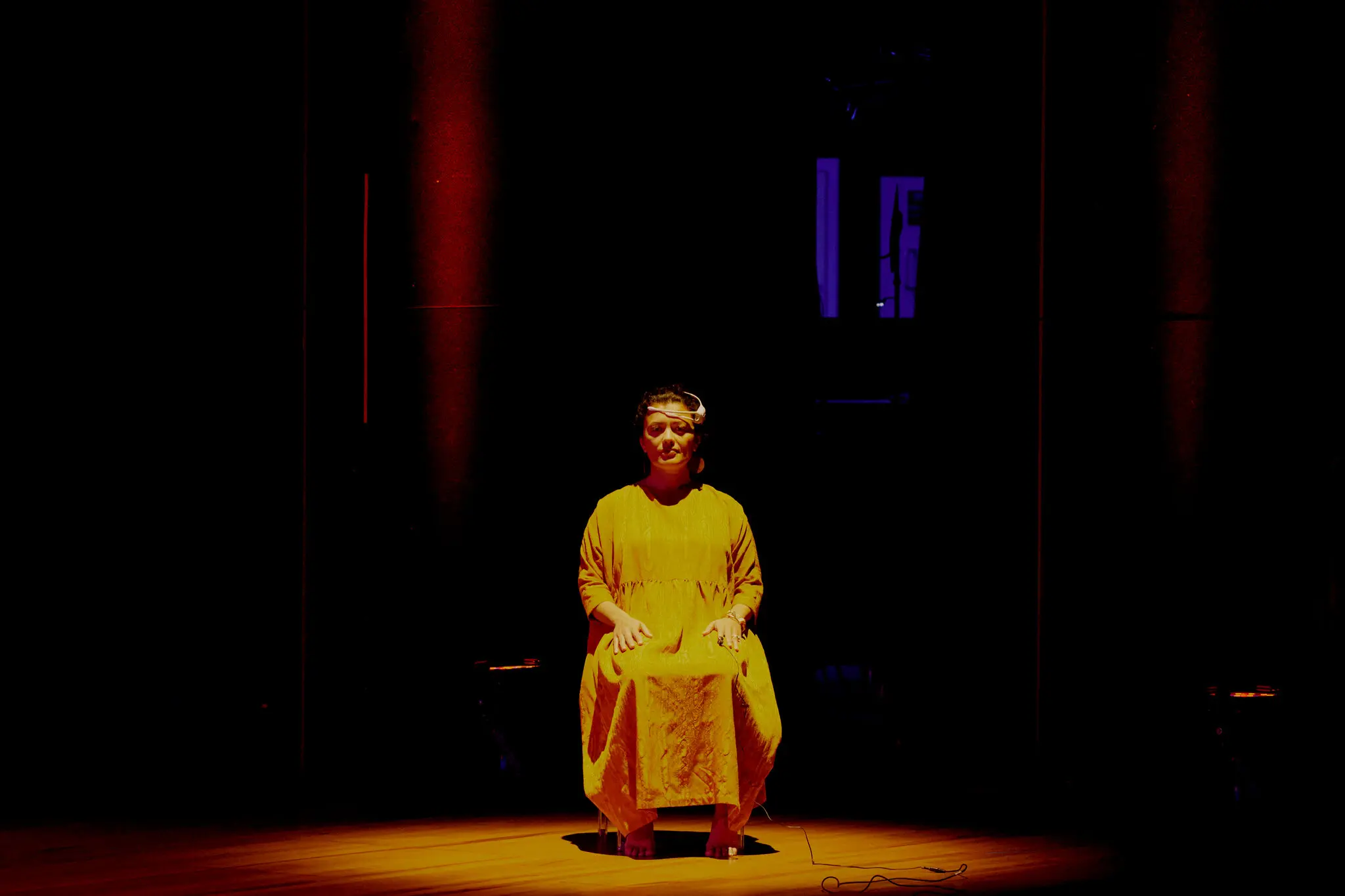

Photo: Bob Seidemann

At thirty-six, T. J. Rodgers—the initials stand for Thurman John—is one of the youngest semiconductor presidents in the United States. Twelve years ago he went campaigning for George McGovern, at a time when everybody was saying they wanted to change the world; now he’s doing it, in ways no one outside the rarefied world of solid-state physics could possibly have anticipated, in ways not even he could have anticipated. For a career in the heady free-enterprise climate of Silicon Valley has convinced him that the best way to change the world is to generate possibilities, to put people to work, to make money.

T.J. slipped his battered red Honda Accord into an empty parking space. The construction crews were already at work across the road, gouging foundation pits into the onion fields for new high-technology ventures. Week by week, month by month, the onion fields and the lettuce fields of San Jose were disappearing, just like the prune orchards and the apricot orchards of Sunnyvale before them. The land was worth more for high technology: it was a law of the market. And the less efficient or agile or lucky of the new ventures would disappear too, bulldozed just like the onion fields. Again, it was a law of the market. The law of the market was the law of the jungle. Only the fit would survive.

T.J. was one of the fit. He wanted to make sure his company would be too. It was fifteen minutes before the end of the graveyard shift. Still time to see how his assembly workers had made out overnight. He slammed the car door and strode into the low-slung concrete building. Behind him the barren slopes of the Diablo Range were glowing red in the dawn.

CYPRESS SEMICONDUCTOR MAKES MEMORY DEVICES—tiny slivers of silicon crammed with microscopic circuitry that store data for scientific instruments and state-of-the-art minicomputers. While “jellybean factories’’ like National Semiconductor and Nippon Electric slug it out mass-producing the lower-technology chips that go into household items like personal computers and pocket calculators, new outfits like Cypress have been popping up to fill niches in the marketplace that are too small or too advanced for the big players to handle. Cypress operates on the outer limits of high technology, manufacturing tiny “scratch pad” memories with circuit features 1.2 microns in diameter (that’s twelve ten-millionths of a meter) and access times as low as ten nanoseconds (ten billionths of a second)—as small and as fast as anything in existence. As T.J. likes to say, he’s been doing things fast all his life.

At age three, growing up on Lake Winnebago on the outskirts of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, he was playing rummy with a neighbor lady for money; at eight it was poker with the babysitter, who had to quit because she was losing all her earnings. He had a serious side as well, one he seldom shared with other people because it mainly had to do with math and electricity. His dad would come home from his job selling used cars and find the sockets hanging out of the walls or the coffeepot rigged up with test tubes. His mom took most of the credit for this. During the war she’d been in WIRES—Women Instructors in Radio Electronics, a corps of female electronics wizards—and T.J. responded well to her coaching.

Sometimes his serious side and his fun side met, with unpredictable results. There was the still he constructed on the lake. There was the radio transmitter he put together to razz the high school principal after he tried to ban cheering at pep rallies. And then there was the time he accidentally blew up the chem lab at Oshkosh High. He was supposed to be working on a science project, but actually he was making a “Thurm-o-Flare,” one of the big smoke bombs he was selling around school with a printed guarantee offering a free replacement if one blew up in your face. It was his last one.

Sometimes his serious side and his fun side met, with unpredictable results. There was the still he constructed on the lake. There was the radio transmitter he put together to razz the high school principal after he tried to ban cheering at pep rallies. And then there was the time he accidentally blew up the chem lab at Oshkosh High. He was supposed to be working on a science project, but actually he was making a “Thurm-o-Flare,” one of the big smoke bombs he was selling around school with a printed guarantee offering a free replacement if one blew up in your face. It was his last one.

T.J. was also a star linebacker on a state championship football team, and so after high school he went to Dartmouth— a school with no football scholarships but with plenty of money for smart athletes. He liked the place, despite its snotty Eastern ways (“T.J.R. VI,” he signed his letters home)—liked its North Country backwoodsiness and its rough-and-ready social life. Gamma Delta Chi was a real animal house—grain-alcohol punch in tubs, gross-out stunts for the dates, gatoring on the floor—and T.J. quickly evolved into a classic Dartmouth animal. But he was also Phi Beta Kappa, the number-two graduate of the Class of ’70, a double major in chemistry and physics, winner of two fellowships to Stanford. Work hard, play hard: that was what he’d learned at Dartmouth.

It was fast becoming a corporate maxim at Cypress. Another corporate maxim was, Only the best. That was the watchword of his hiring policy. In eighteen months the company had gone from seven people to 170, and every one of them, from the shipping clerk to the design engineers, had been the best T.J. could find. His competitors were not so thrilled, since he was hiring away their key people. In his office were six letters threatening lawsuits over Cypress’s hiring policies, each one mounted and framed. T.J. liked to think of people as fish: there were the catfish, who take the hook deep in their gut and put up no fight: the bass, who put up a fight but usually get reeled in; and the trout, who get away half the time. These letters were his trout-fishing trophies.

Certainly it was important to have the right team. There’d been an explosion in new semiconductor ventures since 1981, and it had created intense competition for highly trained personnel, engineers and technicians alike. There were also a few openings for untrained individuals, intelligent people who were eager to learn. For those who didn’t measure up, there was no place at Cypress at all.

IT WAS 7:05 A. M. WHEN T.J. got out of assembly; the yield meeting was already in progress. Yield was a crucial factor in the success or failure of workweek thirty-nine. The term refers to the number of newly minted semiconductors that actually work—maybe half, maybe two thirds of the several hundred chips that have just been laboriously etched onto a four- or five-inch silicon wafer. Yield data is one of the most closely guarded secrets in the semiconductor industry, and one of the most sensitive. High yield means more product, less waste from the expensive, unpredictable process of wafer fabrication.

Semiconductor manufacture requires grappling daily with the surreal realities of quantum mechanics. If you bounce a Ping-Pong ball against a wall, the chance of its passing through is practically nil; but at the quantum level, Ping-Pong balls pass through walls all the time. To order these microscopic particles so that they can carry information as dependably as letters on a page is a highly unnatural act. The law of entropy teaches that chaos is the natural state of the world. T.J.’s whole life has been devoted to defying this law—at the quantum level by manufacturing semiconductors, at the human level by organizing all these people to work together. Yield was one way of keeping score.

Yield was also what would determine whether the goal for this quarter could actually be met. At the moment, revenues from the quarter were less than half what the business plan called for. And yet there were nearly enough orders to meet the plan in the remaining week—if yield were good. If the wafers coming out of the fabricating plant (“fab”) contained enough chips that worked. If not, there was no way.

“I’ve got to go to another meeting,” T.J. said. “Will you guys tell me what happened over the weekend? What are the numbers?”

T.J. appeared completely calm except for a tiny rippling motion in the muscles at the back of his jaw. The daily tension was creating tiny wrinkles there, wrinkles that were not inappropriate on the face of a brash young businessman who had $37 million of other people’s capital—and who stood to become a millionaire himself if his gamble paid off.

“It didn’t look too good,” said a young engineer with a Texas drawl. He rattled off a list of numbers.

“So it’s erratic yield? Four hundred, five hundred, then zero on the other wafers?”

“When I was here last night they ran five zeros and one four-hundred,” the Texan replied. “But I don’t know if they were sorting chiefly rejects or . . . ”

“So you don’t know yet.”

T.J. headed through a pair of high wooden doors into the manufacturing half of the building. There, in a glass-walled room known as the sort area, a bank of machines was probing newly etched wafers with needles and squirting ink on the dies that didn’t respond. T.J. turned to the yield chart, which was hanging on a clipboard on the wall.

As he scanned the numbers his jaw began to relax for the first time that morning. There’d been some problem runs, but the news wasn’t as bad as it sounded. On most runs the yield was consistently high. T.J. grinned. He had a bet with L. J. Sevin, the Dallas venture capitalist who’s chairman of his board, that they’d make their quarter. There was still a chance he could win. The current prediction was that the company would end the quarter shipping $9,000 over the mark—if any of fifteen probable disasters didn’t strike before the end of the week.

Aside from losing his bet and disappointing all his employees, nothing cataclysmic would happen if they didn’t make it. Their goal was triple the goal for last quarter—and they’d only switched on the fabricating plant two months before. The backers would understand. Other semiconductor start-ups take a year to turn on a new fab, run into bizarre yield problems, suck up millions of dollars. And end up with new management.

The Valley was full of engineers who had staked their lives on a dream and gotten bounced out because they couldn’t handle the reality.

That clause in T.J. ’s contract, the one that said he could be fired from his job as president of his own company, fired at any time without cause—that was a standard clause for a Silicon Valley start-up. Right now his company was performing well beyond expectations. He was walking on water. It was a posture he wanted to maintain.

THAT EVENING, AFTER AN ELEVEN-HOUR DAY, T.J. had to go to the Semiconductor Industry Association’s annual Forecast Dinner at the Marriott in Santa Clara. Lehman Brothers, the New York brokerage house, had invited him to a predinner cocktail party, a party at which almost all the guests would be presidents of promising new semiconductor companies that hadn’t yet gone public—companies just like Cypress. T.J. soon found himself sipping wine with a well-scrubbed young stock analyst and trading stories about Jerry Sanders, the banquet’s master of ceremonies.

Jerry Sanders is the president of Advanced Micro Devices, the fastest-growing company in the semiconductor industry. A flamboyant man who owns a Bel Air mansion, a Malibu beach house, and a couple of Rolls-Royces, he is known in the Valley as the King. T.J. worked for him from 1980, after trying and failing to get his first venture funded, until 1982, when he and three of his five vice-presidents quit the company to form Cypress. At AMD he was responsible for a line of memory devices that used a conventional type of circuitry known as bipolar, which is dazzlingly fast but has the drawback of sucking up a lot of power and generating a lot of heat. The idea he outlined in Cypress’s business plan was to duplicate a variety of bipolar chips in CMOS—complementary metal-oxide semiconductors, a promising but technologically troublesome alternative.

CMOS chips require very little power; the problem is that they’ve always been slow. Cypress, however, makes CMOS chips that are not just low-power but fast—as much as ten nanoseconds faster than anything the competition has to offer. To get this kind of performance requires working in dimensions approaching one micron. This puts Cypress right on the edge of fundamental knowledge in physics, in a zone T.J. likes to describe as one manufacturing tolerance away from known disaster. And yet, in its first nine months of production—first manufacturing chips on another company’s fab line and now on its own—Cypress succeeded in introducing six memory chips, each one offering significant performance advantages over an existing product. T.J. was of the opinion that bipolar was going to take it in the chops, and he intended to deliver the blow.

He and the analyst were laughing about AMD’s sales conferences, which are held every year at the Hilton Hawaiian Village on Waikiki Beach. “No wives are allowed for a week,” the analyst said. “It’s sick.”

“No wives,” T.J. declared. “But whatever you can pick up is manhood, right? Large balls.”

“Did you hear about the time he led them to the sea?”

“No!” T.J. sputtered. “But there you go. Hey, every semiconductor president I’ve ever talked to says the same thing about Jerry: ‘The guy does a hell of a job, but I don’t like the son of a bitch.’ As long as we understand the rules, that’s fine. He’d stick me in five nanoseconds if he could, but he can’t—because I’ve got big guys behind me.” This was a reference to the venture capitalists on Cypress’s board. “So he leaves me alone only because he has to, and I leave him alone only because I can’t get as close as I’d like to. And that’s okay! But one of these days we’ll ride into his village, we’ll burn his huts, we’ll rape his women, and we’ll dance on the bones of his children!”

“They’re doing fairly well, ” the analyst observed guardedly.

T.J. nodded. “Jerry Sanders runs the best semiconductor company in the United States.”

“Why do you think that is?”

“Because Jerry Sanders is a salesman and a businessman. He’s not an engineer. He brings back the reality of the marketplace. If you don’t ship the RAM, it’s your ass—which is the way it is. You can make all the excuses about so-and-so going on vacation or whatever, but basically the customer puts out the hand, the RAM falls into the hand, or you lose. Somebody else gets the order, like Nippon Electric. And Jerry Sanders is brutal enough to bring that reality back into his company. I’m trying to do that, too. Like, I dump on people nightly. They understand that life’s unfair.”

Life is unfair: that’s the third maxim at Cypress, along with Work hard, play hard and Only the best. This one was something he learned at his first job, at a place called American Microsystems, where he worked until eleven o’clock every night for five years turning out state-of-the-art memory chips and losing money. The chips were manufactured by a process he’d developed at Stanford, a precursor of CMOS called VMOS. Finally, when it was obvious that VMOS wouldn’t make it, he left American Microsystems, tried and failed to start his first venture, and joined AMD—where, he was appalled to discover, slower versions of the same chips were being sold quite successfully. Until then he’d always assumed, like most Americans of his generation, that life was—or ought to be—basically fair. Now he knew that the best you could do was stay in position to get shafted.

Sanders took the podium after dinner and announced that in China this was the Year of the Rat. “If you know anything about the Chinese zodiac, ” he said, “you know that there are two lucky stars in the Year of the Rat and they represent wealth and power. It means that in the Year of the Rat it’s easy to make money.

“Now, I’m not going to steal the forecaster’s thunder, but I will point out that AMD has grown year-to-date more than 100 percent. Of course, I’d like to point out that that’s because I was born in the Year of the Rat. You’re not supposed to draw the conclusion that I’m a rat. What you are supposed to know is that every five cycles—every sixty years, which means once in a normal person’s lifetime—you have the Year of the Golden Rat. And believe it or not . . . this is it! We’re unstoppable! So, fellow shareholders . . .”

The room exploded with laughter. T.J. hooted.

After Sanders came the forecast, which was indeed rosy, and then an appearance by the Valley’s two congressmen, and then a brief question-and-answer session. Finally the King offered a parting thought. “Just remember,” he said, “that this meal cost you more than the average Chinese earns in a month.”

A ripple of uneasy laughter crossed the floor.

“Oooo!” Sanders squealed. “That was cruel. But then, life is cruel.”

Puzzled titters and a nervous shuffle. What was the King up to this time? T.J. smiled.

“And if you don’t believe me—wait a year.”

THE NEWS AT TUESDAY MORNING’S SHIP REVIEW was good: there was high yield on the wafers that had come out of fab over the weekend, and on some of the reject wafers as well. That meant there were more than enough units to fill existing orders by the end of the week, assuming they could all be assembled, tested, and shipped in time. But something was bound to go wrong somewhere, and since it looked like there’d be inventories on a couple of products, the sales department volunteered to get some last-minute orders. T.J. took his daily four-mile run through the onion fields and returned, fresh and relaxed, for a meeting with a woman from a San Jose ad agency who wanted him to do a testimonial for the real estate developer who was turning all the onion and lettuce fields on Cypress’s side of the road into a high-tech industrial park.

That evening T.J. returned home to find his wife and a friend celebrating a birthday in the kitchen with a bottle of Freixenet. He reached into the refrigerator and pulled out some Louis Roederer brut. “This is the real stuff, ” he declared. “The thing I like about it is it’s got a lot of earth, it’s got a real thick body and a lot of chalk in the nose. You want some, Kathleen? You wanna dump that?”

Back in Oshkosh, T.J. and Kathleen had been high school sweethearts. Fourteen years ago, when he graduated from Dartmouth and she from Marquette, they’d gotten married, but after nine years together they’d split up. For the last five years she’d lived in the Midwest; six months ago, when she decided to move back, Diane came, too. T.J. emptied the glasses of Freixenet in the sink. Kathleen frowned. “It’s okay, ” he said.

“Are you done with that board?” she asked. T.J. dumped his chopped onions into the skillet, the beginnings of a clam sauce he was making to go on the swordfish that was marinating on the counter. “The caves of Champagne, the big tunnels where they age the wines—those are chalk mines,” he continued. “They were dug during Roman times. The chalk was exported to Rome.”

“This is in France?” Diane asked. Wine wasn’t such a big deal in the Midwest. Here in Woodside, in the golden hills between Silicon Valley and San Francisco, it seemed to be all people talked about. Aside from semiconductors and horses, of course.

“Northernmost wine district of France.”

“That’s where we’ll go for our next vacation,” said Kathleen.

“When we were in France we never went to Paris,” T.J. boasted. “We just went to Burgundy, one vineyard after another. We had a great time.”

Diane made tipsy motions.

“We weren’t drinking that much,” he said. “After you leave Dartmouth your drinking goes down exponentially. When you’re at Dartmouth you’re an eighteen-year-old animal and you reach a toxicity level that would be fatal to the average thirty-five-year-old.”

“That’s ironic,” Diane remarked. “I once edited a book on alcoholism that came out of the Dartmouth psychiatry department. It was called Loosening the Grip.”

T.J. laughed. “The infirmary at Dartmouth was called Dick’s house. It was named after a guy named Dick who died and his parents had a lot of money. On big weekends you’d see people being wheeled in, stomach pumps . . . they’d get cut—look at this one.” He pushed up his shirt sleeve to reveal a jagged scar on his forearm.

“I had a disagreement one night at the fraternity. I was wearing my weekend uniform, which was blue jeans, cut-off blue-jean jacket, chain link epaulets. Our group was called the Debauched Hospodars, after a strange, kinky sex novel which was written in the 1900s. I had a big heart on the back of my jacket with LEONA written on it and I had general’s stars on my shoulders and my roommate lent me his track medals, so I had an entire chest full of medals. We’d go down for the parties where the girls would come in from Smith and Holyoke . . .”

“Just like Animal House,” said Kathleen. “I lived through it.”

“The uniforms never got washed. After four years they could stand up. We’d go buy cans of tuna fish and we’d take the oil and give ourselves a nice little jelly-roll hairdo. We’d eat a little tuna and rub a little oil in the chest hairs. Then we’d go to the mixers and these little honeys with flats and starched skirts would be there to see the Dartmouth animals, and they would not be ready for what the real Dartmouth animals were.”

“This was the Sixties?” Diane was incredulous. “It sounds like the Sixties never hit Dartmouth.”

T.J. reached into the cupboard for the clams—little jars of imported Adriatic clams, tiny and tender and flavorful, the best. The cupboard was arranged in orderly rows, clams and capers and cornichons and pâté, Moosehead and Dos Equis and Anchor Steam beer, cherries and pears and gooseberries and mandarin oranges, all in a straight line, labels facing out. It represented one more front in his never-ending war against entropy, one more victory for order.

“We had a little bit of social awareness, ” he said as he strained clam juice into his skillet. “After Kent State they held classes to talk about social responsibility and all that nonsense.”

“The Cambodia invasion was a big deal,” Kathleen reminded him. Despite his years of ROTC, he hadn’t always talked like this. He’d been against Vietnam. He’d put on blue jeans and a hand-embroidered work shirt and campaigned for McGovern with her in ’72. But since then his attitudes had changed. It had begun when he was in grad school, when he realized that you can’t give money to some cause if you don’t make any first. Discovering that life is unfair had only hardened him. He’d gone from Jerry Brown and Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan. Governor Moonbeam, he called Brown now. Jimmy the Wimp. The Seventies embarrassed him.

“Anyway, we were having this little wrestling match at the frat house and this guy offended me and I was, as my father would say, running on seven cylinders. I took a big roundhouse punch at him and he ducked long before the punch got there and I stuffed my hand through a window. So I go to Dick’s house and we’ve got some Harvard nerd there sewing people up. I mean it’s like M*A*S*H, you know? This guy put novocaine in me and I couldn’t feel a thing, but I’m moaning and groaning, and I had this little Southern belle and she’s going, ‘He’s gonna die! Ah jes’ know he’s gonna die!’ Then I hop up, go back to the fraternity, continue the party. That was Dartmouth, circa 1968. But it was just on weekends. I did not drink, I only studied during the week.”

“He worked hard and he played hard,” Kathleen remarked. “It’s two ends of the continuum.”

“But Dartmouth, when you get down to it, was really good training,” T.J. reflected. “It got you ready.”

“Yeah.” Kathleen gave her carrots a stir and took another sip of champagne. “Well, Animal House was antisocial behavior, and I guess that’s the rule of the game. No holds barred. You’re supposed to be constantly beating the next guy. I guess it’s warfare—socially acceptable warfare.”

The clam juice had been reduced by two-thirds. T.J. grinned and splashed some vermouth into the pan.

DAY THREE WAS TAKEN UP in meetings, but T.J. spent most of day four in his office with a camera, taking pictures of chips. On Monday, the day after the end of the quarter, he was scheduled to give a talk in Phoenix at a semiconductor investment conference. The gist of his talk would be: CMOS is taking over the world, and we’re CMOS. Because Cypress was still a private company, he had to make his point without giving away any numbers. The best way to do that was to divert their attention with photos of all his chips.

At this point T.J. was feeling edgy. His talk was four days away and he hadn’t done anything for it yet. He didn’t have a speech. He didn’t have slides to illustrate the speech he didn’t have. He didn’t have photos to make up for the numbers he couldn’t reveal. And any photos he was going to have would have to be processed by 5:00 the next afternoon, which was when the photo lab closed.

T.J. was so busy with his talk that he didn’t take his run until 4:00. Every afternoon at 5:00 there was a “trouble meeting”; it had already started when he got back, so he skipped his shower and came straight to the boardroom in his running clothes, shirt clinging to his back, sweat dripping down his face. Nobody was surprised; the whole company was running hard and fast, and part of T.J.’s job was to personify that commitment.

Greg Belt, a blandly efficient young man whose unofficial job description is chief bean counter, was giving the latest word on the chips as they passed through assembly and test. What the company had shipped to date amounted to three fifths of its goal for the quarter, and if everything went perfectly the goal would be surpassed by Saturday. It wouldn’t be surpassed by much, however: orders were only $12,000 over the goal, $26,000 short of the total that marketing had taken on to sell on Monday.

“We’re having a marketing-limited quarter,” T.J. declared. “You ought to see the letter I’m writing to the investors. After all the turds we’ve been eating all quarter about how you guys are gonna book us out of business . . .”

Fritz Beyerlein, the German-born vice-president in charge of assembly, was sitting in the back heaving deep belly laughs. “I’ll come in with lederhosen on,” quipped Jerry Nalywajko, the Polish-American marketing manager, “and a big paddle.”

T.J. tossed out an idea. “Why can’t I call up the president of Compaq, Sun, one of them—a start-up like us—and say, ‘Hey, friend, I have a $26,000 problem. Buy some of my parts.’”

“I guarantee you what will happen,” said Nalywajko. “He’ll say, ‘Let me talk to my buyer—’”

“He’ll understand the definition of end of quarter. I’ll drive the stuff over myself.”

T.J. and Nalywajko talked over prospects. In ten minutes they came up with a dozen possibilities. If necessary, T.J. would call two of them the next morning and ask them to help put him over the top.

DAY FIVE BEGAN WITH A BANG. T.J. was doing sixty miles an hour in heavy traffic on his way to work when the law of entropy struck back. First he heard an ominous rattle. Thirty seconds later the left front wheel spun off its axle and went bouncing down the freeway, twing!, six feet in the air, twing!, thirty feet down the road, twing!, before wiping out a tree in the median, whack! T.J. looked in his rearview mirror and saw a shower of sparks cascading behind him. He put his foot on the brake and started sliding. A concrete post went whizzing past his window.

By the time he got the car to a halt, T.J. was already worried about being late to work. There was a 7:00 yield meeting that morning, and he’d been telling his vice-presidents for a month they had to start their meetings on time. Working in no-excuses mode meant it didn’t matter if your wheel flew off. Life is unfair. The people in the car behind him were so shocked they stopped to ask if he was okay. “I’m fine,” he said. “Can you give me a ride to work?” He got in at 7:07.

By 5:00—the end of the last business day of workweek thirty-nine—the action at Cypress had shifted from assembly to test and shipping. Three quarters of the goal had been met, and most of the rest was in final test or in stores, ready to go. Two months ago, when the new fab line was about to be switched on, the idea that they could meet this goal had seemed laughable, absurd. Only T.J. had seemed to think it a real possibility. Now it was almost done, and the mood in the company, from the shipping dock in back to the executive offices in front, was a mingling of pride, exhilaration, and disbelief.

At the nightly trouble meeting T.J. took a moment to congratulate everybody on the effort they’d been putting out. He’d been sitting in a cubicle a few minutes earlier, he said, when he’d heard a sales person say they still had fifteen minutes in the western time zone. He knew people had been coming in at seven in the morning and leaving at eight or nine at night. He wanted them to know that this kind of effort was what would separate the companies that win from the companies that lose. And anybody who wanted to move up in the business, that is, on the glamour side of the company, would have to do what he’d just done—attend to a lot of chickenshit details.

He turned the meeting over to one of his vice-presidents. This morning he’d told Kathleen things were looking good for the quarter, so she’d made dinner reservations in San Francisco and invited some old friends down from Napa Valley to meet them. And although he didn’t know it yet, she had a surprise for him when he got home: she’d wallpapered the dining room. It was something they’d talked about doing for years, but first there hadn’t been enough money and then she’d gone to the Midwest and started a new life—new friends, new career, new home. They’d kept in touch and gradually started seeing each other again, but it was a long time before she decided to move back. Now she was on sabbatical from her teaching job—her career was training people in the health care field: nurses, administrators, other teachers—and she had a few more months to make things final.

T.J. got a ride home with one of his engineers. “Is that you?” Kathleen asked as he came in the door.

“Yep. Car’s not quite ready yet. Seems it did a little more damage than we thought.”

“Thurman, next time when I say take the other car and leave your car home when it sounds like it’s falling apart, you’ll do it, right?”

T.J. shook his head and grinned. “I truly didn’t think that car was going to blow up on me this morning.”

Kathleen was frowning. Just over a year ago the president of Eagle Computer had been killed when his Ferrari spun off the road on the same day his company had gone public, making him a millionaire. Why had T.J.’s wheel flown off anyway? The car had been making strange noises ever since it came out of the shop. The garage mechanic swore he’d tightened all the nuts; maybe he had and maybe he hadn’t. But Cypress was a hot company and there were probably lots of people who wouldn’t mind if T.J. . . . “Oh, Thurman,” she said, “I don’t like it at all.”

But T.J. wouldn’t hear of it. They got into Kathleen’s car and headed for a French restaurant near Nob Hill that was arguably the most expensive in town. Their dinner partners were people they’d met in Palo Alto while campaigning for McGovern. Jeff had been a Nixon supporter. He and T.J. had argued while Kathleen and Linda became friends; before long, they were inviting one another over for dinner. When Jeff finished his residency at Stanford he and Linda moved to Napa and bought a vineyard. Which was why, over escargots, T.J. was asking him about tax shelters.

Politics didn’t come up until dessert, an assortment of pastries and sorbets with glasses of Chateau d’Yquem. This time T.J. and Jeff agreed. Kathleen was in despair. Health care depends on public support, something that has not been forthcoming in this era of the tax revolt and the budget cut. T.J., on the other hand, had become enamored of the idea that state support dulls the spirit, while the knife-edge of competition hones it. He didn’t believe in cutting off the needy, but he thought private contributions less wasteful than government support. And besides, he preferred to focus his attention on the people at the other end of the continuum—the able, the intelligent, the ones who can contribute. “I come home and I read her Ronnie articles,” he said, “and it pisses her off because she knows I’m right.”

Kathleen sighed. “Linda, are you a Democrat or a Republican?”

“She’s a commie pinko Democrat,” Jeff said.

Kathleen was thrilled. “Are you really?”

“My grandfather was a Democrat, ” she said, “and always voted Democrat from the time he could vote.”

Jeff laughed. “This guy got all the papers, saw every newscast, and told me he voted straight Democratic ticket for the last seventy-five years. I said, ‘Hey, pops, why buy the papers, why watch the newscasts, if you’re going to vote straight Democrat?’ And he said, ‘I’ve analyzed it, I’ve studied it, and I’ve never seen a Republican worth voting for yet.’

“But you know, he lived in the era when that was right. He worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad. They’d be told there were jobs in Pittsburgh, they’d get on a train, travel six hours, find the jobs were taken, and then travel six hours back. No pay for twelve hours of travel. And he also retired at sixty with hemorrhoids and got a pension till he was ninety-six and died. These are the guys the union saved.”

“In the days when the unions were necessary for survival,” Kathleen added.

“They still are necessary,” T.J. said. In his experience—working construction as a student—unions were pretty useless, but he knew there had been a time and a place when they did more than raid your paycheck. He knew, too, that most of corporate America didn’t subscribe to the entrepreneurial mystique of the Valley, the idea of sharing the excitement and the stock. “If you took General Motors and Ford and maybe Chrysler and turned them loose with no counterbalancing force, they’d shaft everybody who works for them.”

“Look what they did!” said Jeff. “They get the workers to give concessions and then one year later they hit megabucks—”

“And then all the executives give themselves bonuses.” T.J. gazed at his Sauternes in disgust. “That really pissed me off.”

T.J. was feeling rowdy after dinner, so he and Kathleen went to North Beach and strolled up Broadway, past the strip-joint barkers and the lowlifes and the punks, to a sidewalk café overlooking what T.J. liked to call the zoo. They sat at a table with a pair of scuzzy-looking Texans who were knocking back beers and ogling the girls. Guys with mohawks and chains lounged against the lampposts. A long-haired kid in a leopard-skin vest strode through the crowd.

“I need a vest like that,” T.J. announced. “It could be a symbol—like, whenever I wear my leopard-skin vest, somebody’s gonna get fired.”

“Thurman, ” Kathleen said, “go back to tuna fish.”

“I think I’m in love,” said one of the Texans. A chauffeured Mercedes had just disgorged a striking young female in a blue dress and white stockings. She was followed by a world-weary man in his early forties. T.J. thought he recognized him.

“Frank Caufield,” the man said.

“Hi, Frank!” Venture capitalist. T.J. rose instantly to his feet. Caufield is a partner in the San Francisco capital investment firm of Kleiner Perkins, Caufield & Byers. When Cypress was working on its first round of financing, T.J. and his vice-presidents had met him to get his approval on the investment.

As Caufield and his date took a seat at their table, T.J. told them about his accident that morning. “But, hey!” he said. “Today was a tremendous day because the pressure was off, so all the bitching about how hard I was driving people was over. And then I go to the meeting where we’re gonna tally up the dollars, and it’s overcrowded! Ordinarily I have to drag people in. And the mentality—suddenly it’s not me kicking your ass, it’s all of us trying to make the thing work. That caught today, for the first time—which means I can die and the thing will cruise by itself. That was the upper of the day. Plus or minus a dollar, I don’t care.”

Kathleen grinned. “Have a cigar, Thurman.”

DAY SIX USUALLY BEGINS WITH A RUN through the nature preserve next to T.J.’s home, followed by brunch at Mama’s, a ferns-and-oak place in the Stanford Shopping Center. Today T.J. and Kathleen intended to renew an old friendship with one of T.J.’s professors from Stanford, William Shockley. It was Shockley who led the Bell Laboratories team that invented the transistor, the basic building block of semiconductor technology. He was also a seminal figure in the development of the Valley, for it was his Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory that spawned the high-tech culture there. After his protégés left, Shockley—his business a shambles—retired to the distinguished and normally quiet calling of teaching electrical engineering at Stanford. That was where T.J. had encountered him, at a point when the furor over his theories about eugenics—the idea that mental ability is genetically determined—had in most circles eclipsed his fundamental contribution to twentieth-century living.

T.J. and Kathleen had grown friendly with Shockley and his wife; the man they saw was not a raving bigot but an engineer with too much faith in logic. The first thing he did when he sat down at their table was look at his watch. He’d forgotten he had a radio interview at 12:15. It was already noon; he could afford to be five minutes late, but traffic was getting heavy because there was a ball game, so he could only allow eleven and a half minutes for brunch. He ordered a glass of orange juice.

T.J. offered sympathy over the outcome of his libel suit, which had just ended in a judgment of one dollar against a former Atlanta Constitution reporter who’d linked Shockley’s proposals for voluntary sterilization of the “genetically disadvantaged”’ with the genetic experiments of the Nazis. Then he turned to Kathleen with an anecdote from school days. “When I was in his class, we had an exchange student from Kenya, I think it was—”

“Nigeria,” Shockley said.

“Nigeria. And one day we had a demonstration—we had a lot of them in those days—and these people came into the room and they were raising hell.”

“Ku Klux Klan uniforms,” Shockley said.

“That’s right. So Shockley’s got his tape recorder going, which he uses to tape all his classes, and he’s got his Polaroid, which he uses to take pictures of the blackboards, and he’s trying to reason with them—only that’s not what they’re there for. And in the middle of it all this exchange student jumps up, voice trembling with emotion, and says, ‘Professor Shockley, why did you tell me that no matter how well I did in your class, you’d flunk me?’

“So the same day we went upstairs and he played the tape, and what he actually said to the guy was, ‘You’re not doing so well in the class, you’re probably going to get a C, so I suggest you audit the class instead of taking it for credit.’

“That’s one of my standard speeches to newsmen,” Shockley said. “I say, ‘Say that back to me. I’m not sure it was communicated.’ I do these wonderful lectures to my graduate students, everything done perfectly, and I look at the papers and obviously something’s gone wrong with the transmission.” He looked at his watch again and announced it was time he left for home. “If you’re interested in some of the human quality things,” he said, pulling out an oversize envelope, “I grabbed a couple of items which I’ll leave with you.” Then he shook hands and was gone.

“Classic Shockley,” T.J. declared.

“He hasn’t changed much at all,” Kathleen said as she pulled a sheaf of correspondence and article reprints out of the envelope. The first item was a paper Shockley had written for Leaders magazine, a limited-circulation monthly with articles by Lewis Thomas and the president of South Korea and poetry by Emperor Hirohito. “The effectiveness of leaders,” Shockley’s contribution began, “will deteriorate on a worldwide basis by the year 2000 because of the action of dysgenics on their followers. Dysgenics is the name for backward evolution caused by the excessive reproduction of the genetically disadvantaged.”

T.J. rolled his eyes. Only the best was one thing as a corporate slogan, quite another as social policy. But that was Shockley, more interested in being “right” than in what other people think. And what if he were right? What would you do about it? Sperm banks for the gifted? Voluntary sterilization for the less fortunate?

Kathleen suppressed a giggle. “I’d be afraid of what would come out of me if I used his sperm. I mean he’s a nice guy, but . . . ”

February 1, 1985

February 1, 1985