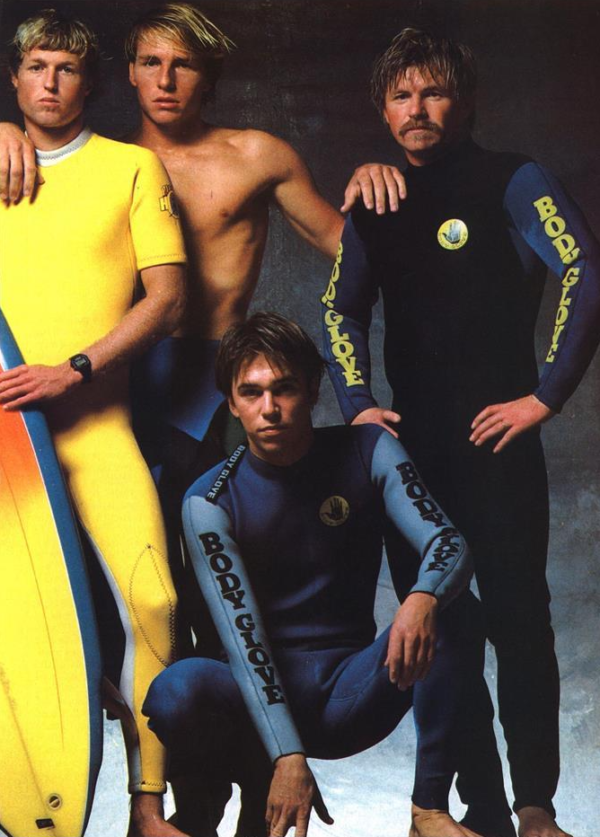

South Bay surfers, temporarily beached: Dennis Jarvis, Dave Forrest, Matt Warshaw, Mike Purpus. Photo: Norman Seef

THE PACIFIC WAS GRAY-GREEN AND FORBIDDING. Dark clouds hung low over the beach, fueled by the smokestacks of the generating plants just up the coast, almost smothering the tankers anchored offshore. A dozen surfers were out in the water, bobbing up and down like ducks, fighting over some mushy, two-foot-high waves. It was eight o’clock on a chill winter morning.

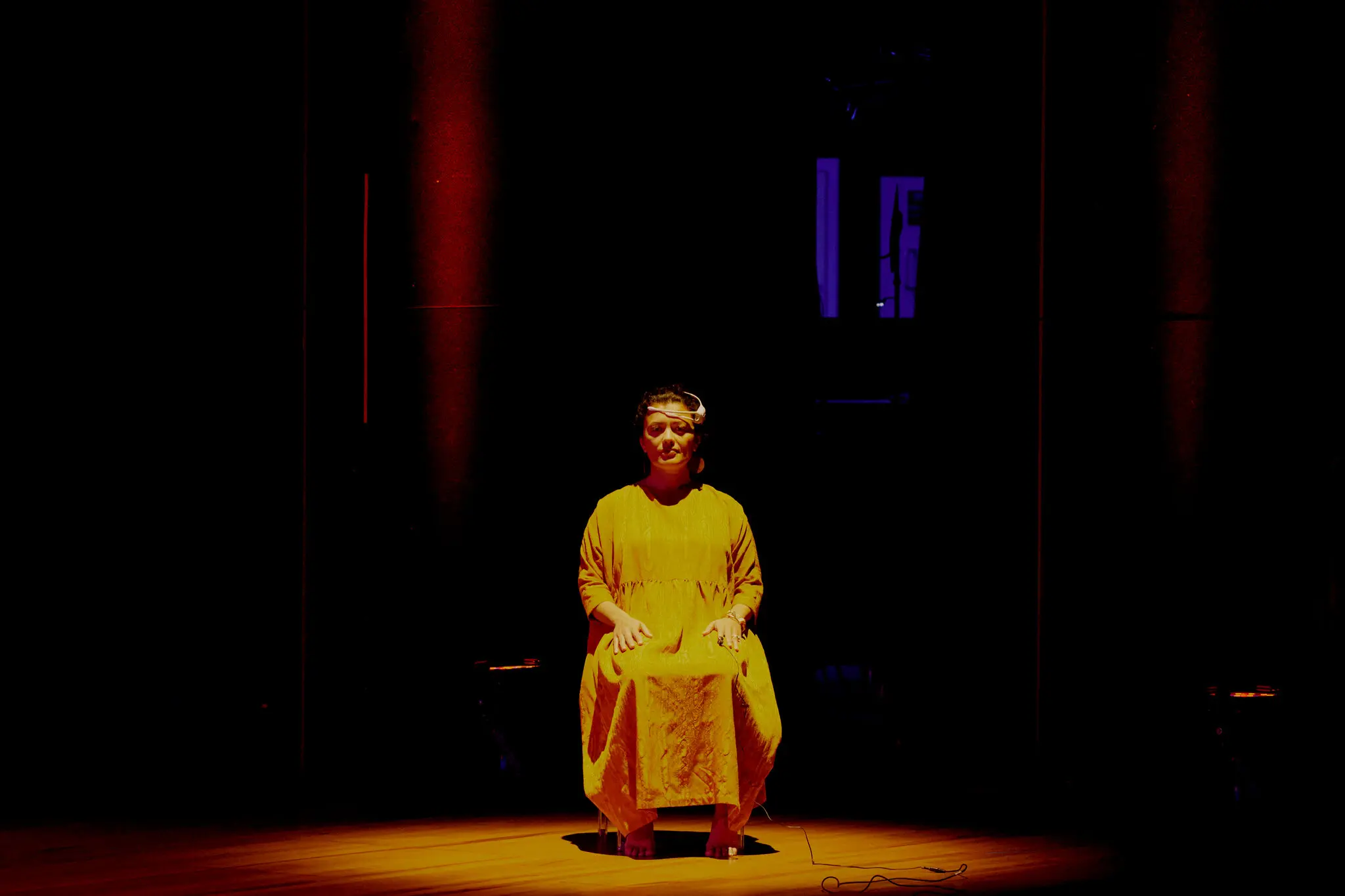

Out of the murk on the beach walked a young man with a camera. He had been scheduled to shoot an ad for a wet-suit company that sponsors one of the dozen dark-suited figures in the water, but the weather was too dismal. He was twenty-seven, his hair was long, and he was wearing bell-bottom jeans. We started talking about environmental issues—the winter sewage spill in Malibu, for instance, which closed the beach for weeks. “There’s a lot of potential,” he said, “if surfers could just come together as a group.” A slight, almost sheepish-looking grin flickered across his face. “I dunno, is that too idealistic?”

Out of the water ran the surfer he was supposed to shoot. His name was Dennis Jarvis, and at twenty-one he was of a different generation. “Not too good out there,” he shouted, thrusting his short orange board into the sand and shaking the seawater out of his curls. “What a bummer.”

We were standing on the shore at Hermosa Beach, California, a tiny Los Angeles suburb whose name means “beautiful” in Spanish. Hermosa is part of a trio of beach towns—Manhattan, Hermosa, and Redondo beaches—that line the southern end of the Santa Monica Bay, whose forty-mile crescent of shoreline gives Los Angeles its window on the Pacific. Developed as summer-resort communities after the turn of the century, these South Bay towns remained isolated until the Sixties, when the sprawl finally hit. Today little trace remains of the nineteenth-century rancho whose white-duned beaches laced with wild verbena inspired the name Hermosa. Instead the shoreline is cluttered with houses and condos and generating plants and tank farms and fishing piers, and the towns themselves are filled with shopkeepers and office workers and movie technicians and aerospace personnel—and surfers, which explains why at the foot of Hermosa’s main street, where any normal town would have a statue of some veteran, a bronze surfer stands forever poised on the perfect wave.

We were standing on the shore at Hermosa Beach, California, a tiny Los Angeles suburb whose name means “beautiful” in Spanish. Hermosa is part of a trio of beach towns—Manhattan, Hermosa, and Redondo beaches—that line the southern end of the Santa Monica Bay, whose forty-mile crescent of shoreline gives Los Angeles its window on the Pacific. Developed as summer-resort communities after the turn of the century, these South Bay towns remained isolated until the Sixties, when the sprawl finally hit. Today little trace remains of the nineteenth-century rancho whose white-duned beaches laced with wild verbena inspired the name Hermosa. Instead the shoreline is cluttered with houses and condos and generating plants and tank farms and fishing piers, and the towns themselves are filled with shopkeepers and office workers and movie technicians and aerospace personnel—and surfers, which explains why at the foot of Hermosa’s main street, where any normal town would have a statue of some veteran, a bronze surfer stands forever poised on the perfect wave.

Dennis Jarvis is something of a celebrity here. He’s a pro in a town where surfing is the leading profession. Other surfers ride Dennis Jarvis boards; their kid brothers wear Dennis Jarvis T-shirts. He surfs the beach at Thirtieth Street almost every morning he’s in town. The rest of the time you’ll find him in Australia or Hawaii or South Africa.

The South Bay is where surfing was introduced to America. It was brought over from Hawaii as a tourist attraction, although its appeal was limited by a reliance on 120-pound redwood boards that tended to pitch nose-first into the water. By the late Fifties, however, fiber glass and other materials developed by the southern California aviation industry were being employed to produce boards that were light, inexpensive, and easy to ride. Then Gidget hit, followed by the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean, and the image of the South Bay surfer was projected nationwide. Clean-cut and blond, these sun-blessed youngsters led lives that were defined by a leisure-time pursuit—and wasn’t that the way of the future?

Surfing never really went away after those golden years, it just turned mean. These days you’re likely to get into a brawl in the water and end up with a chunk bitten out of your back. There are too many surfers, and not enough surf to go around.

The way people surf has changed, too. Nobody tries to become one with the wave anymore. Now the idea is to push the limits. Surfers compete to perform radical maneuvers that demonstrate not union with the wave but mastery over it. This new attitude has been encouraged by changes in surfboard design. In the Sixties, the typical board was eight or nine feet long and easy to ride but hard to maneuver. Most boards now are six feet long or under, and so zippy they almost demand a superaggressive stance.

A similar attitude prevails on land. Historically a hangout for bikers, beatniks, hippies, and low-riders as well as surfers, Hermosa Beach today has the look of a place where all the pop-culture phenomena of the past have come to rest as sediment. The outward appearance is harmonious and agreeable: a modest town sloping down toward a broad, sweeping beach, nestled between the rocky headlands of the Palos Verdes Peninsula to the south and the distant ramparts of the Santa Monica Mountains to the north. But the reality is somewhat more complicated, as the bartender who had his nose bitten off by a patron crazed on angel dust will no doubt attest.

All across the Los Angeles basin, madness has been reasserting itself as the number-one mode of expression. Mellow vibes and the laid-back life-style have become relics of a rapidly receding past. Violent crime has a grip that cannot be shaken. A recent phenomenon is the drive-by shooting, in which pedestrians are picked off at random from a passing car (two in West Hollywood in one night). Then there were the freeway torture-murders—two sets, one homosexual and one heterosexual—in which hitchhikers who chanced upon the wrong van were raped and tortured and thrown away.

Surfers feel the madness too and respond in different ways. In suburban Orange County they’ve seized upon punk as a ritualized form of aggression: lead pipes with three-inch-long spikes, sinks and toilets ripped from walls, longhairs reduced to pulp in the parking lot. In the wealthy enclave of Palos Verdes, the surfers keep to their own rugged coves and regard outsiders as poachers in their private preserve. There they surf in the classic manner, donning plain black wet suits and cruising the waves on long, white boards. Here in Hermosa Beach they have colorful wet suits and short, multicolored boards and stay away from P. V. lest they be stoned while climbing up its rocky cliffs or return to find their tires slashed and their windows broken. Instead they practice radical maneuvers on their overcrowded beaches and compete for the stardom that comes with professional success. Christianity, oddly enough, is often a major force in their lives.

Punks, cruisers, Herms. Dennis Jarvis is a Christian Herm.

THE WRITING ON THE WALL SAID “DEFECTIVE YOUTH.” Eddie Talbot, the thirty-two-year-old proprietor of E.T. Surfboards, gave a little grunt of dismay and walked inside. A native of the Bronx, Talbot moved to California as a teenager and has been hooked on surfing ever since—first on the sport, then on the business. He started out working part-time in Greg Noll’s shop (Noll was one of the legendary surfers of the Sixties); now he employs fourteen people and sells more boards than anybody else in Hermosa Beach.

One of his employees is Dennis Jarvis, who started out as a fourteen-year-old rug rat—underfoot every day, driving everybody nuts. Eddie figured if he was going to hang around he might as well do something, so he put Dennis to work pumping polyester resin into containers. By the time he turned eighteen, Dennis was airbrushing boards, and then he decided to try shaping them as well. Now he’s one of E.T.’s star shapers.

Surfboard manufacture is a peculiar blend of synthetic materials and manual technique. The board begins as a chunk of featherlight polyurethane foam that is shaped to the customer’s specifications: length, width, rocker (curvature), number of fins, kind of tail, and so forth, all according to his height, weight, and surfing style and proficiency, not to mention the type of waves he intends to ride. (Obviously you need a different board for the two-foot beach break at Hermosa than for the fifteen-foot tubes of Hawaii’s Banzai Pipeline.) After shaping and sanding, the board goes to the laminating room to be wrapped in fiber glass, “hot-coated” with resin, sanded, and hand-sanded again. Then it goes to the glossing room for airbrushing and another coat of resin, and finally to the polishing room for its last sanding. The finished product costs upward of two hundred dollars and could last for ten to fifteen years, barring accidents; but most surfers progress so rapidly that they need a new one every few months.

Dennis makes two lines of boards for E. T.—Dennis Jarvis Spyderboards (the name inspired by a comic strip in Mad magazine) and Dennis Jarvis Pro Designs, which cost a little more and get added attention in the shaping process. The royalties he gets make E.T. one of the major sponsors of his career, but the shop means more to him than that. It is his family, his home—the only real home he has.

He’s seen surfing go from a long-haired, soulful thing to what it is now, with kids scrambling for sponsors and contests suddenly cool again.

Dennis’s parents broke up when he was six. His mom remarried—once or maybe twice, he can’t remember. His dad disappeared; he’d always told them that one day he’d head out for Tahiti or someplace and nobody would ever know what happened to him, and then a couple of years ago, when everybody called on his birthday, he was gone.

“It was no biggie,” Dennis said, shrugging his shoulders and staring at the floor. “I don’t know . . . it was his decision, I guess.”

When Dennis was in high school—he went to Mira Costa, which of course was the surfer school to go to—Eddie used to steal him away whenever a big swell came in so they could head up to Malibu together. Eddie’s like that—sort of an older brother. Whatever the kids are into, he takes the philosophical approach.

Instead of hippies it’s jocks and punks, and instead of mellow vibes it’s amped-out aggression. “It’s just cycles,” he shrugged. “It was time for a new trip. People got sick and tired of love and peace, and they wanted something different—that’s all.”

ALL THIS AGGRESSION IS AT LEAST GIVING CALIFORNIA a boost in world surfing circles. In the early Sixties, of course, Californians dominated the sport; but as the Gidget era faded, Australians began to take over, and then Hawaiians and South Africans, and now California is in fourth place, just ahead of such up-and-comers as Japan and Brazil. This has something to do with the waves (Hawaii has better surf because it has no continental shelf) and something to do with the public attention (Australia treats surfing like a major sport—almost like football in America), but mostly it has to do with the attitude of the surfers. For a long time, Californians were just too laid-back to compete.

Professional surfing didn’t begin until 1965, and it didn’t really get under way until ten years after that, when a Hawaiian contest promoter started the International Professional Surfing Association. IPS set up a rating system and a worldwide contest circuit, which keeps serious contenders on the road for three quarters of the year. California got its first IPS-sanctioned event in 1980 with the U. S. Pro Invitational, which joined ten other contests in Australia, Bali, South Africa, Brazil, Japan, and Hawaii to form the 1981 circuit.

It is possible to win the IPS crown without entering most of these contests, but it’s not very likely. This puts a lot of pressure on would-be contenders to get their business trips together. That means assembling a portfolio of all the media coverage you’ve received and taking it around to potential sponsors—sportswear, swimsuit, wet suit, and surfboard companies—along with a smooth-sounding speech about all the benefits they can reap by sending you halfway around the world. Unfortunately, like the good surfing spots, most potential sponsors have already been taken.

The scramble for sponsors makes surfers especially media conscious. The media they care most about are Surfing and Surfer, nearly identical magazines that feature lots of color action photos, plus interviews with surfing hotshots and articles like “The Ten Best Waves in the World” and “Surfing Beyond Planet Earth.” The undisputed media stars in the South Bay area are twenty-two-year-old Mike Benevidez and twenty-one-year-old Chris Barela. Not coincidentally, Benevidez and Barela—the two live together, travel together, surf together, and invariably are spoken of in the same breath—are also the only South Bay surfers sponsored for the entire IPS circuit. Most surfers, like Dennis Jarvis, can’t afford to make every IPS event and have to pay their way to some of those they do make with money they’ve earned outside. That gives them less time to surf, and that in turn makes it difficult to perfect a winning style.

Dennis’s style is amped-out and radical. He favors a real slash-and-tear approach, always putting himself in critical positions on the wave and recovering at the last moment. A couple of years ago he was so abrasive it hurt your eyes to look at him. People used to call him the disco surfer. Now he’s a little more polished, but he still rips up the waves. One of his favorite moves is a vertical off-the-lip, in which the board goes straight up the face of the wave, hits the lip, pivots, and charges back down like a roller coaster. Asked why he surfs this way, he grinned and said, “The more you can do on a wave, the funner it is!”

Mike Purpus started surfing in 1959, when he was ten, and by the time he was fourteen he was being flown around the world with his girlfriend to do promotional appearances for a line of surfboards with his name on them.

When he isn’t traveling, Dennis lives with a recreational surfer, Dave Forrest, in a pleasant little house on a narrow street just over the hill from the beach. His neighborhood—full of small, well-kept houses set very close to each other in orderly rows, with tiny lawns out front and cars parked bumper to bumper in the street—is the kind of place that reminds you how polite, how civilized, people have to be to live together. Every morning he gets up early to surf, and in the afternoons he works at E.T., and then he comes home and maybe goes to the beach to watch the sunset and walks back up to the little Mexican place on Manhattan Avenue for dinner, and after that he and Dave and a couple of the guys will sit around and watch television or something. There’s a fireplace in the corner of the living room, and on chilly nights Forrest will build a fire and the flames will bounce off the surfboards rowed up in the kitchen and people will drop off to sleep on the sofa. Someday, perhaps, Dennis will go back to school and learn to apply his airbrushing skills as a commercial artist; but that’s off in the future, and this is now. It is the surfer’s dream life-style.

There are a couple dozen surfers like Dennis in California—promising young professionals who are not as accomplished as Benevidez or Barela or Joey Buran (who in 1980 became the first Californian to win an IPS event when he took the Waimea 5000 in Rio) but who are eager to break into those ranks. They hit all the California contests, like the Breakwater contest in Redondo Beach and Katin Pro/Am in Huntington Beach (sponsored by Nancy Katin, the eighty-one-year-old swimsuit manufacturer who is the grande dame of California surfing), and they do as much of the IPS circuit as they can. As a group they are hardworking, ambitious, and wholesome—sometimes disturbingly wholesome, as was the young Christian surfer who drew stares at the Katin contest a year ago when he ran down the beach screaming, “If your member causes you to sin, cut it off!”

WHEN DENNIS WAS GROWING UP, HIS MAIN hero in life was a guy named Mike Purpus. Actually, Purpus was a lot of kids’ hero back then. Out of all the surfers of the Sixties, Purpus was the one whose life epitomized the glories and the opportunities that surfing had to offer. At Mira Costa High School, he was God.

He was the West Coast champion at twenty, the U.S. champion at twenty-two, and he was still the U.S. champion when he retired eight years later. He even had a photo spread in Playgirl, and until Proposition 13 was passed, he was getting a hundred bucks an hour to show surf movies of himself at the local high schools.

These days he works as a bartender at Castagnola’s, a steak-and-lobster place on the Redondo Beach pier. In its dining room, leisure-suited tourists sit in Naugahyde captain’s chairs amid an expanse of fake rigging and watch the surfers down below as they ride in toward the concrete parking garage on the beach. Purpus started working there two and a half years ago. It was the first time he’d ever had to take a job, but aside from having to cut his hair he has no complaints.

“My timing put me right on top of the gravy train,” he told me one evening as the last customers were finishing their drinks, “and that carried me around the world.” But there’s no way anyone could duplicate that timing today. For there is no gravy train in surfing anymore, just a lot of people fighting over scraps. So surfers band together in tiny groups to keep outsiders at bay—the survivalist ethic at work. Mike got so bummed out he wrote an article about it in Surfing a few years back, and his feedback was a ton of letters from people who said if they ever saw him surfing in their spot, they’d kill him. Then he was surfing at Carlsbad one day and somebody actually tried—ran his surfboard into Mike’s ear while he was paddling out and then started boasting to his friends that he’d killed Mike Purpus. “I call the whole thing localism, that’s what I call it,” Mike said. “And it could terminate the sport.”

Lunada Bay is a mystical spot, jealously guarded not only by the surfers in Palos Verdes but by nature as well: by sheer cliffs and razor-sharp rocks, by shallow reefs and poisonous sea urchins.

Of all the seaside communities in California, the one with the worst reputation for localism is probably Palos Verdes. There are no real beaches in Palos Verdes, just a string of rocky coves. There’s no industry there either, and no urban sprawl, and a minimum of condos and shopping centers; just mile after mile of rolling suburban lawns set atop sheer cliffs that rise majestically above the crashing Pacific. People aren’t crowded together there, but they still feel pressured—the money, the cars, the need to keep up. Palos Verdes is the L.A. business community’s answer to Beverly Hills. It also has the best surfing spots in the area.

Most of the kids there don’t surf, and those who do are rebels—not hardened juvenile delinquents, exactly, but not future lawyers and bankers either. They prize their surf spots in direct proportion to their distance from the beaches where other kids surf. The first one you come to is Haggerty’s, where some of the locals have been threatened at knife point. The next spot is the Cove. It was the trail to the Indicator, one of the four reefs in the Cove, that the local kids lined with broken bottles a couple of years ago. Then there’s Lunada Bay, the one place where outsiders still don’t venture.

“It’s guys who’ve been surfing there for years,” explained Castagnola’s busboy, who lives on the Torrance Riviera, the condo strip between Redondo Beach and P.V. “They all know each other, and there are just enough waves for them. It’s like on a tennis court where everybody has to wear white. They don’t want some radical coming out on the tennis court with smelly old cut-off jeans and taking the best courts. They want everybody to pay their dues.

“But there have been a lot of barbaric acts—guys sitting on top of the cliffs and, you know, if you see an outsider, you throw rocks at him. I dunno. If you wanna get psychological, I’d say it’s frustration more than anything that causes people to do those things.”

THE RIDE TO LUNADA BAY IS SOMETHING in the nature of an ascension. From E.T. you drive through the neon clutter of the Pacific Coast Highway to Palos Verdes Boulevard, which advances through the Riviera to Palos Verdes itself. Suddenly, around a bend and over a hill, the condos vanish and you’re in a deep wood, staring at a single Georgian mansion set jewel-like on a distant hillside. Then there’s a dip and a curve and you begin to climb.

The bay itself, a half mile wide, is like a perfect Roman amphitheater dropped rudely into the cliffs. Across the street are homes out of Architectural Digest, low-slung mansions with Mercedes-Benzes out front and tennis courts peeping up in back. Ahead is nothing but sea and sky. Every night around sunset, a dozen or so cars will be parked by the road. Thirty or forty kids wearing Top-Siders and buttonfly Levi’s will be leaning against them, drinking beer. It’s sort of a religious rite: evening vespers at Lunada Bay.

It’s not simply that Lunada Bay is one of the few big-wave spots in California (twelve to fifteen feet on good days, has been surfed as high as twenty); or that to surf here you almost have to have grown up within sight of the place; or that the asking price for a vacant lot in the neighborhood is $1 million—although all these things are important. The point is that Lunada Bay is a mystical spot, held in awe by the small fraternity who surf it regularly, jealously guarded not only by them but by nature as well: by sheer cliffs and razor-sharp rocks, by shallow reefs and poisonous sea urchins. This is a place that forms a rare bond, which is why the people who surf it call each other “brother” and “sister.”

I sat one day in Brett Cooper’s living room as Jeffrey Sumrall rolled up his pants leg to display a jagged, three-inch gash in his shin. Chris Tronolone pointed to the spot on his cheek where fifteen stitches had been taken a couple of months before. Brett recalled the friend who’d had his nose split open and his left arm temporarily paralyzed when he was thrown off his board and landed face first on a reef. They talked about the dangers of surfing the Point, out by the wreck of the freighter Dominator, and of “going through the alley” between the Point and the big rock just inside it. Said Brett, “You don’t go through the alley and come out clean.”

As one of the four shapers in Palos Verdes, Brett occupies an almost priestlike position among P.V. surfers. From his garage, and from the garages of his friends Chad, Angelo, and Zen, come the long, white boards that rule the waves in Lunada Bay. Brett goes to junior college in Torrance now and lives in a Riviera apartment, but he grew up across the street from Haggerty’s. He doesn’t want what happened there to happen to Lunada Bay.

“People,” he said. “They come and they really don’t respect the past. When I was younger, I used to feel like it was my duty to go out and keep the art of surfing going. Our crew would be keeping good order, too—one person to a wave. See, when you have order, that means everyone is having a good time, and the surfing’s better, too.

“The younger kids look up to us now. Of course, none of us encourage them to throw rocks. I’m twenty-four years old. I don’t go out and pop anybody’s tires. But if people come around and think they’re hot stuff, they’re not gonna get anywhere with us.”

“Those kids at the Hermosa pier,” said Chris, “they’re just out there to show off.” Chris, Brett’s roommate, is variously known as “Ayatollah,” “Fonzie,” “Rhino,” and “Relish.”

“What’s happened is that there are two completely different schools of surfing that have evolved,” said Brett. “They’re out in contests, out for the hot maneuvers. We’re into taking a wave and riding it from start to finish. The contest is more between you and the wave than between you and your fellow surfer. But we aren’t down on their scene. I groove to what they’re doing. It’s just that they’re calling us babies— and yet when it gets down to it, we’re the ones who tackle the surf on the raw days.”

AT THE OPPOSITE EXTREME FROM LUNADA BAY is the surfing spot known as Shitpipe. The name comes from a sludge pipe along the bottom that acts like a reef, causing waves to peel off in both directions. Tank farms and generating plants and a sewage treatment plant make the water taste oily and foul and the beach turn sticky with tar. Shitpipe is where the South Bay’s punk surfers hang out.

Punk hit surfing about the same time skateboarding died out. Skateboarding was really big for a while; there were skateboarding leagues and contests and champions and even a SkateBoarder magazine, brought to you by the folks at Surfer. Concrete bowls were constructed so pubescent kids could perform radical off-the-lip maneuvers that would leave ordinary mortals dripping from the sides like so much scrambled egg. The energy that came out of these bowls was predictably hard-edged and wild. So when the bottom fell out of skateboarding, a lot of kids simply turned that energy toward the ocean.

A lot of them discovered punk at the same time—which is to say, they discovered a ritualized form of aggression with mass-media credentials and a link to the Mother Country. There were punk clubs in Hollywood where nouveaux bohemians affected spike haircuts and black leather, but the suburban kids were not like that. The suburban punks had skinheads and wore swastikas, boots, and chains—and unlike the Hollywood punks, they had no qualms about tearing things up. They were for real.

For the kids in Hermosa, punk for a long time centered on what the band Black Flag was doing. When people talk about the horrors of punk rock, Black Flag is what they usually have in mind—concerts that turn into riots, music that sounds like mealtime for wild animals, songs about white pride and worse. Black Flag moved into the church in the middle of town at a time when Hermosa Beach was still terminally mellow. There were hippies everywhere, and to walk around with short hair was to risk getting beaten up. By the time Black Flag left, the town had gotten pretty much punked out.

The church is a large stucco structure that had faithfully served its congregation for decades before being abandoned. A bunch of longhairs took it over and tried to convert it into a “New Age Artists Cooperative,” which the city was trying to close, and then Black Flag moved into the sanctuary. They’d throw a party and three or four hundred people would show up and the hippies would get uptight. Somebody would bust out a window and the stained-glass maker who lived upstairs would come down and say, “These hands create. Why must you destroy?” But what the hippies couldn’t accomplish, the cops could. So when the end finally came—when Black Flag saw that they were being driven out of town and there was nothing they could do about it—the band threw a going-away party and ripped the place apart.

A similar thing happened to the Fleetwood, the only South Bay rock club that tried to draw the punk crowd. After that, there was no place for local punks to go. But different currents were being felt by that time, anyway. In the beach towns, at least, it was almost as if the extraordinary wave of energy was beginning to bum itself out. Surfers began to let their hair grow longer, and a lot of them started getting into Christianity. You still see kids in kerchiefs and chains in Hermosa Beach, but now you’re likely to see them in places like Hope Chapel, up by the highway in the converted bowling alley.

HOPE CHAPEL STANDS like a beacon at an intersection on top of a hill. Next to it is a supermarket, underneath it is an exposed parking garage, and inside, where the bowling lanes used to be, is a hall of worship. Eleven years ago it was nothing but four people in an abandoned storefront; now it has fifteen hundred members and has spawned twelve daughter chapels in California, Hawaii, Montana, and Texas. Its founder is a soft-spoken, attractive young minister who came here from Glendale at the command of a Voice. His message is that God and the Bible are real. Surfers have been big at Hope Chapel from the beginning. “A lot of people won’t touch the beach people,” said Perry Ching, the associate pastor. “We’re not afraid of them.” He added, “This church is like a hospital. It’s a place where people can meet people. That’s why we call it the people place.”

“The People Place” is the name of a little booklet, available in the Hope Chapel bookstore, that explains how the chapel can help you establish “a personal relationship with God” and “a joyous life-style based on God’s viewpoint.” Baptisms are conducted on the beach, or in a hot tub when the weather is bad. There are Sunday-morning worship services, Friday-night concerts, and Christian study groups that meet in the middle of the week. There’s a Christian ski team, a Christian surf team, and a Christian volleyball team. Those who still have time to flout God’s Word are reprimanded—first in private, then in public if they fail to mend their ways. “It’s tough,” said Ching. “Discipline and love.”

“Perry calls this place a hospital,” said a friend of Dennis Jarvis’s, Ron Williamson, a twenty-four-year-old surfer who gave up his apartment near the beach to sleep on Ching’s floor. “I call him a heart specialist, because he works on the heart.”

Williamson is a towheaded, freckle-faced young man who came to know Jesus after his uncle’s sudden death in a car wreck made him realize how fragile human life really is. He was seeing a Christian girl then, too—but when that didn’t work out, he took his eyes off the Lord. He got pretty wild there for one summer, and then he got tired of spinning his wheels and he asked the Lord to take him back. “Now I feel much more peace,” he said. “I don’t feel like I’m rebelling anymore. It’s neat, you know?”

Dennis made his initial acquaintance with Jesus through television. He was in the eighth grade at the time, and when he was in the tenth grade he was thinking about God a lot. But then he backslid and got to be more of a normal kid. A couple of years ago, he even had a rock band—not exactly hardcore punkers (“We were more in with the pseudo-punks”), but nonetheless a ska band with supershort hair. They called themselves the Jetsons and played parties, high school assemblies, and even a couple of clubs. But then Dennis had to go to South Africa for the Gunston 500 and they broke up. When he came back it seemed like he and most of his friends felt more like praying every day.

“We just felt kinda empty,” he explained one day between boards at E.T. “We were surfin’ and stuff and we didn’t feel fulfilled, because we were just going out and partying and everything.” He took a deep breath.

“What really happened was we got scared into it. The Iranian crisis really had a lot to do with it. And a lot of it I guess is because of the way the times are changing. It seems like everything that’s going on nowadays relates to the Book of Revelation. It’s pretty scary, actually. So we started thinking about that, and lately we’ve just been sitting around listening to the radio and reading the Bible and stuff.”

Dennis’s interest in the first-century Revelation of Saint John the Divine grew out of the Christian fellowship he has going with a couple of guys at the shop—the laminator and the glosser—and his introduction to the latest Hal Lindsey book, The 1980’s: Countdown to Armageddon. Lindsey is the South Bay evangelist whose first look at Biblical prophecy, The Late Great Planet Earth, is touted by his publisher as “the best-selling non-fiction book of the decade.” Countdown to Armageddon is an update that predicts apocalypse in our lifetime. It is also an anticommunist, antiwelfare, anti-Trilateral Commission, anti-Council on Foreign Relations, pro-South Africa political tract—in short, a fast-talking bible of ultra-right-wing Fundamentalist Christianity. It is found in every Christian surfer’s bedroom.

Lindsey cites several twentieth-century developments—the rebirth of Israel, the rise of Russia and China, and the emergence of OPEC and the Common Market—as signs that the stage has been set for Armageddon, which will begin with an Arab-Israeli war and end with the Second Coming of Christ. He promises that before the Tribulation—the seven-year period of agony between the rise of the antichrist and Armageddon—all true Christians will be snatched from the earth to join God in heaven. He adds that their sudden disappearance will be explained to the nonbelievers left behind as the work of flying saucers rather than the fulfillment of ancient prophecy. This is why so many surfers believe UFOs to be demons of Satan.

The tricky part is that no one, not even the angels in heaven, knows exactly when it’s going to happen. (“It could come at any minute,” said Dennis, “and I wanna be prepared.”) However, by accepting Jesus in your heart now—an option Lindsey calls “Plan B”—you not only get into heaven when you die, you also get his personal assurances that you will miss the entire reign of the antichrist. In return, God doesn’t even expect total perfection— merely a place in your heart.

“But it’s best just to stay in line,” Dennis said. “Like if you’re in your parents’ house and you gotta follow the rules—it’s like that with God.” The sex part, admittedly, isn’t easy. Yet compared with the imminent destruction of the world, even the lure of the flesh begins to pale. “And with the love of Christ,” Dennis offered, “you don’t have that drive.”

The worldly rewards are manifold, he added. “Christian surfing brings surfers closer together. You’re not out there to rip people off anymore. You’re just there to be with your friends and have a good time in the sun and the surf that the Lord provides. It’s really just one way of getting a little bit more love out of the world.”

March 1, 1982

March 1, 1982