THERE WERE WAYS IN WHICH THE FIRST WEEK IN APRIL was like any other on the 15th floor of 100 Universal City Plaza, the black glass tower on Lankershim Boulevard that serves as headquarters of MCA Inc. Lew Wasserman, the 82-year-old patriarch who led MCA for the past half-century—first as president, then as chairman—drove in every morning from Beverly Hills after receiving his pre-dawn briefing via phone and e-mail from company executives around the world. Thomas P. Pollock, executive vice president in charge of motion pictures, rode in the customized info-van (phones, fax, computer) that allows him to commute from Montecito and stay as up-to-date as his boss. Sidney Sheinberg, MCA’s president, and his longtime associate Tom Wertheimer, executive vice president for television and home entertainment, took their places at their offices down the hall. The difference was that every day brought new reports that MCA’s corporate owner, Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. of Japan, was in talks to sell the company—talks that no one had bothered to convey to the four men who direct its operations. Matsushita president Yoichi Morishita had decided to cash out and somehow, inexplicably, Lew Wasserman had not made it onto his phone sheet.

Morishita didn’t call, but others did; hour after hour, the phones rang with reporters, business associates and old friends who hadn’t been heard from in years, all of them hungry for facts. Sid Sheinberg, whose calculated outbursts during the past seven months had been instrumental in persuading Morishita to sell, was characteristically hot-tempered in response. Wasserman revealed nothing. An imposing man whose oversize glasses and shock of platinum hair give him the look of an Old Testament prophet who’s gotten a Beverly Hills makeover, he knows better than anyone the link between power and aura. The aura he projects is one of mystery, of unseen authority. To part the veil in a moment of weakness would be unthinkable. As for his employees, the 15,000 whose livelihoods depend on the decisions made by the four men who occupy the 15th floor—well, as one MCA veteran put it carefully, “The population of the company is waiting to see what will emerge.”

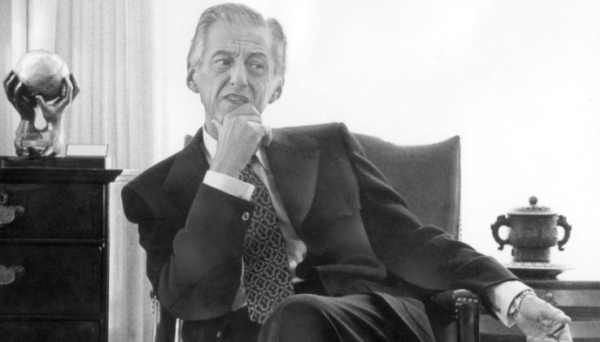

Lew Wasserman in 1973, the year he was named chairman and CEO of MCA.

The population of the company: it’s a phrase that would only be used at MCA. For 33 years now, since MCA abandoned its agency business for movies and music and theme parks, the corporate city-state known as Universal City—415 acres of mostly unincorporated territory surrounded by the City of Los Angeles, home to a vast entertainment enterprise with outposts across the globe—has been led by Lew Wasserman. Now its people had to face the likelihood that Wasserman would not be there forever. It was all but unthinkable—not just because they were so afraid of him, of the legendary rages that would begin with an ominous tapping of the sword-like letter opener on his immaculate antique desk and proceed to a fury so total that it could leave a grown man in a $1,500 suit hugging the toilet in fear, but because they were so grateful for the security he gave them, for the sense that as long as he was there they could feed their families and not worry about the future.

Read more about the Hollywood agencies in Frank Rose’s book

The Agency: William Morris and the Hidden History of Show Business

“Classic stuff, this book.” —David Rensin, author of The Mailroom

“My wife used to say I didn’t have to worship him,” says Albert Dorskind, the former MCA vice president who created the Universal Studios Tour. “I could just admire him.”

“I’ve seen more of him than any other human on earth,” says Sid Sheinberg, “probably inclusive of his wife. Mr. Wasserman has an integrity and a sense of responsibility that is unbelievable. This is the core of his strength. Everybody knows that when he speaks, he speaks the truth as he sees it.”

“Thinking in Hollywood is tremendously parochial,” says Sam Goldwyn Jr., who’s known Wasserman for 50 years. “It’s the desperation of the day-to-day. Lew Wasserman thought of where things are going.”

Where things are going: In many ways, it feels as if he took them there. In the late ’30s, when Wasserman arrived from Chicago, Hollywood was the movie colony, run for the benefit of the New York-based theater circuits that controlled the film business. A decade later, with television stealing audiences from movie theaters, Wasserman had the breakthrough perception that movies and television could coexist. In the early ’60s, after Justice Department lawyers forced MCA out of the agency business on antitrust grounds, he realized that movies and politics needed to coexist. A few years after that, when other studios were trying to sell off their back lots, he recognized that movies and theme parks were compatible as well.

Movies, television, politics, theme parks: Put them together and you have the formula for Hollywood’s evolution from movie colony to capital of a global entertainment industry, a multibillion-dollar enterprise that decides how people the world over spend their leisure time.

Wasserman has worn many hats—talent agent, visionary, empire-builder, godfather—but through it all he’s been the consummate deal-maker. In a town where the deal is the primary art form, his deals have been more beautiful than anyone else’s. Which is why, even more than the lack of respect shown by the Japanese owners, what shocks people is the way the Matsushita deal unraveled five years after it was done. How could Lew Wasserman and Sid Sheinberg make a deal in which they ultimately lost control? “That’s the unanswered question,” says one player on the lot. “Because it certainly wasn’t the plan. The plan went awry.”

Or did it? Would Wasserman really make a deal to sell the company and come away with less than he wanted?

“Put your money on Wasserman,” counters an old Hollywood hand. “Not Sheinberg, Wasserman. Wasserman is brilliant. And he never loses.”

IN DECEMBER, 1936, WHEN HE JOINED JULES STEIN’S Music Corp. of America, Lew Wasserman was a 23-year-old high school graduate whose show-business experience was limited to a job as a theater usher and a stint as press agent for a Cleveland nightclub. MCA was the leading band agency of the big-band era, with programs on network radio and clients on the order of Xavier Cugat, Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman and Guy Lombardo. The son of an impecunious Indiana dry-goods merchant and his invalid wife, Julius Caesar Stein had started out playing in bands, then started booking them when he realized it could be more lucrative. At first it was a sideline while he pursued his professional career, working as an assistant to a leading Chicago eye surgeon. But in 1924, when Stein and a college chum launched MCA in a two-room office in the Loop with $1,000 in capital, the sideline took over.

Stein transformed a helter-skelter trade into a relentlessly efficient machine, one that turned talent into a commodity and the commodity into money. Soon he was driving a Rolls-Royce convertible and living in a chateau overlooking Lake Michigan. He and his wife, Doris, later moved to New York, but their social ambitions could never be realized in a place where true status depended on that little “Myf” next to one’s Social Register entry, signifying an ancestor who’d come over on the Mayflower. Then Doris thought of relocating to Hollywood, where everything was make-believe anyway.

To herald MCA’s arrival in the movie colony, Stein commissioned Paul Williams, the black society architect whose houses were quite the thing with the Hollywood crowd, to design a headquarters in Beverly Hills—a white-columned mansion across from City Hall, with sweeping staircases and a cut-glass chandelier that would glitter through the night and a freestanding Ionic colonnade outside his windows for that contemplative touch. Wasserman, who’d been hired as national director of advertising and publicity at $60 a week, was brought out to the new office, and in 1940, Stein named him vice president in charge of the new motion picture division.

It’s a career that has seen Hollywood grow from a New York outpost to the capital of a global entertainment industry.

Wasserman and Stein moved quickly, signing established stars such as Bette Davis and buying out smaller agents such as William Meiklejohn, who handled Jane Wyman and Ronald Reagan. In 1945, they bought Leland Hayward’s agency as well, acquiring such clients as Jimmy Stewart, Gene Kelly, Myrna Loy, Billy Wilder, Alfred Hitchcock, Dorothy Parker and Dashiell Hammett. Meanwhile, Wasserman had made his first million-dollar deal, signing Reagan to a seven-year contract at Warner Bros., which put Wasserman in the top rank of Hollywood agents. Then an antitrust suit filed by a disgruntled San Diego dance-hall operator prompted a federal judge to denounce MCA as “the Octopus,” its “tentacles reaching out . . . and grasping everything in show business.” In the resulting shakeup, Stein named the 33-year-old Wasserman president and assumed the post of chairman.

Wasserman, Stein declared, was “the student who surpassed the teacher.” He was also a hopeless grind, putting in long days while the owner entertained powerful associates in his glamorous hilltop hacienda, collected 18th-century antiques (which he then leased to the agency) and studied the tax laws for relaxation. Aside from his capacity for hard work, Wasserman had two things going for him: a personal warmth that made him more palatable to stars than Stein, whose manner was clinical at best, and an astonishing facility for numbers.

The book of show business is written in numbers, and Wasserman, even today, can read it like few others. He can total a column at a glance. He can follow the box office hour by hour when a picture opens and predict its total gross by the end of the day. He can tell you how an MCA recording artist did at a show in Akron the night before, or what a picture grossed in South Africa. “It’s like the fascination of a person who loves crossword puzzles,” says Sheinberg. “He loves the game.”

Then, too, there was his ability to cut a deal. In 1948, with Bill Paley eager to establish himself in broadcasting, Wasserman executed a series of raids on NBC talent—Jack Benny, Amos ’n’ Andy, George Burns and Gracie Allen—that turned CBS into “Paley’s Comet.” In 1950, when Universal was a faltering studio devoid of stars, he cut a deal for Jimmy Stewart to make Winchester ’73 for 50% of the net. It was not the first back-end deal in the picture business (William Morris had gotten 25% for Rita Hayworth four years earlier), but it was certainly the biggest. Wasserman’s most breathtaking deal came in 1952, when, after venturing into television production when most television was broadcast live from New York, he obtained an exclusive waiver from his client, Screen Actors Guild president Ronald Reagan, just as a guild rule against agents producing for television was about to go into effect. By the end of the decade, MCA was not only the biggest seller of talent in Hollywood, it was the biggest buyer as well.

The warmth Wasserman showed to clients did not extend to employees. Within the confines of Stein’s “White House,” Wasserman was a forbidding figure, cold and austere, the toughest of a tough breed. A story went around that showed just how tough that could be: Everywhere Wasserman went, it was said, he would hear such praise for one of his agents—how smart the fellow was, how lucky MCA was to have him—that he finally called the man in and fired him, on the theory that any agent who was so well liked couldn’t be doing his job. One former insider insists the story is apocryphal: “Nobody at MCA was ever that popular, so it wouldn’t have been an issue. Remember, these were guys who ate their kids for breakfast.” But in the late ’60s, when future superagent Sue Mengers was new to Hollywood, she met Wasserman at a party and asked if it was true. Wasserman smiled enigmatically and said, “You guess.”

The deals continued. In 1958, before the market for films on television had been established, Wasserman agreed to pay $10 million in cash and an additional $40 million over time for syndication rights to all Paramount films made before 1948. That same year, when it became apparent that MCA’s television subsidiary, Revue Productions, had outgrown the cramped lot it was leasing in Studio City, he closed on a deal to buy the Universal lot for $11 million and lease part of it back for $1 million a year for 10 years. Three years after that, he bought Universal itself, along with its parent company, Decca Records.

By this time, MCA had developed a reputation for arm-twisting that made it the most controversial enterprise in show business, pilloried in the press and hounded by Robert F. Kennedy’s Justice Department, which convened a federal grand jury in Los Angeles to consider criminal antitrust charges. Documents in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library (of which Wasserman is now a trustee) show just how heated the debate was: When Newton Minow, chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, delivered his “vast wasteland” speech deploring the plethora of game shows, formula comedies and violent Westerns on television, a vice president of the McCann-Erickson advertising agency wrote confidentially that Minow should really be after MCA, because its power “is the basic source of much of the mediocrity on America’s TV screens.”

By the spring of 1962, it was clear that MCA would have to give up either its agency business or its production business, and with the agency bringing in a fraction of the revenues that television was generating, there was no question which would go.

MCA WAS NOW IN SOLE POSSESSION OF THE LOT it had bought from Universal four years earlier—374 acres on a hill standing athwart the northern terminus of the Cahuenga pass. Wasserman had been wary of the purchase at first: Real estate meant overhead. But Revue Productions needed space, and Albert Dorskind, MCA’s chief negotiator on the deal, saw opportunity, even though the property was in such disrepair that the underpinnings of the sound stages were being washed away in the winter rains.

Dorskind hired a consultant and came away with proposals for hotels, restaurants, even an apartment complex along the Los Angeles River. Wasserman had a more pressing concern: what to do with the commissary, which was losing $100,000 a year. Dorskind wanted to replace it with a cafeteria, but Decca president Milton Rackmil told him motion-picture stars wouldn’t eat lunch in a cafeteria. Dorskind was at the Farmer’s Market one Saturday when he saw tourists filing out of a Gray Line bus for lunch and had a brainstorm: Why not have tour buses drive through the lot and stop at the commissary when the studio folk weren’t using it? They could jack prices up 20%, keep the commissary busy all day long and charge the bus company $1 a head in the bargain. He phoned the president of Gray Line, and Universal City became a tourist attraction.

Along with the talent agency, MCA abandoned Jules Stein’s headquarters in Beverly Hills, trading its film-set glamour for a corporate tower. The new MCA headquarters, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, house architects of the postwar glass box, was a squat black tower of glass and anodized aluminum, as austere and forbidding as Lew Wasserman himself.

Universal is now a 420-acre corporate city-state known as Universal City.

Meanwhile, Dorskind kept buying land to give them a buffer. “I felt like Bismarck,” he says today. “Like my natural destiny was to own everything around me.” The state sent in bulldozers to lower the hill, using the fill to extend the Hollywood Freeway across the San Fernando Valley and leaving Universal City more accommodating to development. Wasserman resisted expanding the tour, but after more studies, he finally ponied up $4 million and told Dorskind to go ahead. Special trams were designed, restrooms and food courts were installed, and on July 4, 1964, the Universal Studio Tour was officially inaugurated. Soon the commissary was losing money again.

On the other hand, the television side was performing tremendously, thanks in part to a young attorney Dorskind had hired, a UCLA law school instructor named Sid Sheinberg. Jennings Lang, who headed new projects at Universal Television (as Revue was now known), put Sheinberg in charge of long-form productions—made-for-TV movies such as NBC’s World Premiere series. Sheinberg quickly caught Wasserman’s eye. Among the things that impressed the boss was a 1966 memo outlining ways Gov. Edmund G. (Pat) Brown Sr. (whom Wasserman was supporting in his reelection bid against Republican challenger Ronald Reagan) could appeal to younger voters. Reagan won, partly because he had massive support from Stein and from Taft Schreiber, the head of Universal Television. Yet Wasserman regarded Sheinberg’s analysis as brilliant.

Universal’s movie business was doing less well. When MCA acquired the studio, there was brave talk of it sparking a renaissance in American film, which seemed moribund compared to European cinema. Instead, a string of flops, from Thoroughly Modern Millie to Sweet Charity, left the company nearly $100 million in debt. “They thought it was going to be a snap,” says one MCA veteran.”They found out it was not.”

In the spring of 1969, Wasserman faced a challenge from Jules Stein himself. Embarrassed by the poor showing and encouraged by Schreiber, who’d started in 1926 as Stein’s messenger boy, Stein had begun talking about ousting his protégé as president. Wasserman promptly suffered a heart attack—a mild blood ailment, actually, but it was billed as a heart attack. Word of the scheme to supplant him was leaked to columnist James Bacon, who lambasted Stein just as a host of jet-setters were flying in for the gala opening of the new Sheraton Universal Hotel. Lang and other key executives went to Stein with the message that if Wasserman went, they would, too.

Stein got the picture. When the board met the following Monday, Wasserman was given an extension on his contract as president. Meanwhile, sources say, Edie Wasserman, a forceful woman who’d never inured herself to the snubs of the imperious Doris Stein, gleefully plotted the payback. Three top executives were dumped. Schreiber stayed—”Lew knew when to stop,” says one insider—and the incident was never mentioned again.

Shortly afterward, Lang was put in charge of a production unit at Universal Pictures and Ned Tanen, who’d started in MCA’s mailroom in 1954, was put in charge of youth-oriented pictures (budgeted at less than $1 million). When Lang made Airport and Tanen came out with Diary of a Mad Housewife and, three years later, American Graffiti, MCA’s luck began to turn. Meanwhile, Sheinberg was elevated to president of Universal Television, which was by far the leading supplier of programming to the networks, producing such hits as Ironside and Marcus Welby, M.D. and accounting for as much as 30 per cent of the shows on prime time. Then, in 1973, at the age of 77, Jules Stein decided to retire. The board appointed Wasserman chairman and CEO and Sheinberg, then 38, president. It was not the first time a young man had been named president of MCA.

THE ’60s WERE A BAD TIME FOR HOLLYWOOD generally—the studio system irretrievably defunct, the once-great studios chewed up and spat out by go-go conglomerates, the action centered in swinging London and jet-set New York while geriatric film execs donned Nehru jackets and tried desperately to keep up. But Wasserman, who’d emerged as the de facto leader of the industry, had a larger agenda. The experience of being a scrap on Camelot’s table had left him determined never to be without pull again.

Within a year of the agency bust-up, Wasserman had established himself as one of the Democratic Party’s leading contributors. After the Kennedy assassination in 1963, he became tight with Lyndon B. Johnson, who asked him to continue his fund-raising. Together with Arthur Krim, chairman of United Artists, he formed the President’s Club, hosting celebrity-studded galas for big donors and inventing, it’s said, the 11th seat, which allowed the President to eat a course at each table. He turned down Johnson’s offer to become secretary of commerce; instead he persuaded Jack Valenti, Johnson’s most trusted aide, to become president of the Motion Picture Association of America, the studio alliance founded to stave off censorship demands in the ’20s.

“Wasserman was one of the first to realize that Hollywood could have clout in government,” says Goldwyn. “He said, ‘We can be an influence—but don’t kid yourself, it means patronage.’ ”

As the godfather of the industry, its capo di tutti capi, Wasserman took the lead in labor negotiations. “One of his great strengths,” says Tanen, who resigned as president of Universal Pictures in 1982 to go into independent production, “was his ability at the last moment to stop a strike, to get the union and the companies together and bang heads.”

Other studio chiefs tended to regard Wasserman as dangerously liberal, but Wasserman realized that unions were a fact of life. The question, he explained to associates, was how to view them: friend or enemy? The nice thing about deciding they were friends is that when you help your friends, they generally help you.

In 1974, after eight years as chairman of the Association of Motion Picture and Television Producers, the labor-relations arm of the Motion Picture Association, Wasserman stepped down. His influence continued. It was much the same at MCA, where Sheinberg’s ascension to the presidency seemed little more than an announcement that he was the designated successor. “Sid is extraordinarily bright,” says one who was close to both men, “bordering on brilliant. And he’s an extraordinary deal-maker. I think Lew saw a lot of Lew in Sid. But I don’t think he gave Sid a chance to run the company.”

Sid Sheinberg, MCA president, and Lew Wasserman at Universal City, 1984.

Not that Sheinberg didn’t make his mark: When the original director of Jaws was deemed not right, Sheinberg threw the project to Steven Spielberg, who’d just finished The Sugarland Express for Universal. Sheinberg was stimulating and full of energy, and he had an easy rapport with creative types like Spielberg. But Wasserman still functioned as de facto production chief, and whenever anyone at the studio encountered Sheinberg, Wasserman was usually nearby.

For more than 20 years now, the relationship between Sheinberg and Wasserman has been the subject of intense speculation. The two have lunch together at the commissary nearly every day, but most of their dealings take place out of sight, on the 15th floor. The situation is complicated by the obvious differences between them: For all his facility at deal-making, Sheinberg is garrulous where Wasserman is guarded, hotheaded where Wasserman is coldblooded, rough-hewn where Wasserman is razor-sharp. The easy answer is to paint it as a father-son relationship, but that suggests an intimacy outside the office that no one claims to have observed. A better guess may stem from Stein’s remark about Wasserman, that he was the student who surpassed the teacher. Sheinberg, it would seem, is the pupil who took years to get out of grad school.

IT’S BEEN NINE YEARS NOW SINCE THE PEOPLE of Universal City celebrated Lew and Edie Wasserman’s 50th wedding anniversary with an evening of revelry on the Hill. The site was the town square set on the back lot, where To Kill a Mockingbird was shot in 1961 and Back to the Future in 1984, done up for this night to look like Cleveland in 1936: the May Co. store, the theater he’d worked at as an usher. . . . It was a scene worthy of Francis Ford Coppola, the godfather being feted by his friends and retainers. And at the center of it all was Wasserman himself, warm, solicitous, thinking not of himself but of the comfort of his 700 guests: Henry Kissinger, Lady Bird Johnson, Bill Paley, Angela Lansbury . . . and over there, in a summer gown, Jackie Foster, wife of producer David Foster and longtime friend of Sheinberg’s wife, actress Lorraine Gary. Suddenly Wasserman materialized at Jackie’s side, sleek and catlike, bearing a satin jacket with the Universal logo. “Honey, it’s too cool,” he said with a kiss on the cheek. And then he was gone.

“I love this man,” says David Foster, who produced The River Wild for Universal. “If there’s anyone I could emulate, it would be Lew Wasserman.”

That party was a peak moment for Wasserman—perhaps, in tandem with the even more extravagant fling MCA threw five months later on Stage 12 to celebrate his 50th anniversary with the company, the peak moment of his career. At 73, he was not just the most powerful man in Hollywood; he was the Moses who’d led the business through the wilderness. And now it was time to think about letting go a little, about letting Sheinberg run the company.

The turning point, one insider says, came that same year, when MCA was in joint discussions with a broadcasting company to buy WOR-TV in New Jersey. MCA was hoping to build a new network, and even if it didn’t, it needed a group of stations to launch its programs into syndication. It was a Saturday. The bids were due Monday. Sheinberg was in New York when he got a call from MCA’s acquisition partner: They’d decided the price was too high. He phoned Wasserman in Beverly Hills and asked what he wanted to do. “It’s your company,” Wasserman is reported to have said. “What do you want to do?” Sheinberg wanted to go for it, to buy the station outright. “Well,” Wasserman said as he hung up, “do it.”

Sheinberg had started to take a stronger hand in running the company after the phenomenal success of Spielberg’s E.T. in 1982. He’d put his people in key executive positions: Frank Price, who’d come out of Universal Television, in charge of motion pictures (until the 1986 box-office fiasco Howard the Duck); Tom Wertheimer, whom he’d hired from ABC in 1972 to be his prinicipal negotiator, in charge of television. But after the WOR deal, the organizational charts were redrawn. Wasserman kept three areas—labor, real estate and tax matters. Eventually, those went too.

Wasserman remained involved, but in an advisory capacity. More and more of his time was being devoted to good works: Besides the Kennedy Library, he sits on the boards of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Foundation, the Carter Presidential Center and the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. He’s also a trustee of the Jules Stein Eye Institute at UCLA, and his wife is on the board of the Motion Picture & Television Fund and Foundation, which boasts an Edie and Lew Wasserman Wing at its hospital in Woodland Hills.

Gradually, the tone of MCA had changed, from the relentlessly grasping enterprise once known as the Octopus to something increasingly cautious. Wasserman, a reformed gambler, had always combined an aggressive business stance with a hard-nosed, bottom-line approach that ran counter to the jackpot mentality so prevalent in the industry. But in the ’70s, as the business continued to evolve, MCA had begun to seem loath to change with it. How much of this was due to Wasserman and how much to Sheinberg it is difficult to say, since they worked so much in tandem. But as one filmmaker who’s worked closely with both of them puts it, “The question about Lew Wasserman is: Where is he brilliant and visionary, and where do his tight-fisted instincts get in the way?”

Hollywood insiders can cite many instances, and not just at Universal, of projects that were rejected as too pricey only to generate enormous profits elsewhere. But one that may have marked a turning point was the Raiders of the Lost Ark deal, which Tom Pollock—then an attorney, later Frank Price’s replacement as head of Universal Pictures—made for producer George Lucas.

“Within MCA, there was furious debate about whether to take this deal,” says a source. “But Lew and Sid, it drove them crazy. As far as they were concerned, that deal was asking for unheard-of pieces of profit and ownership. And they passed on it, because it was something that went beyond their definition of how things should be.”

A similar pattern emerged in executive compensation. As other studios began to offer eye-popping pay packages, MCA held fast to the “golden handcuffs” philosophy instituted by Stein—stock options that vested over time and sweet-sounding retirement packages. Combined with Wasserman’s and Sheinberg’s penchant for loyalty, this resulted in a lot of old blood. A case in point: Tom Pollock, whose capabilities as a deal-maker have not been matched by his track record as a picture executive. Not only does Pollock reportedly lack relationships with major stars and directors; in a business of gut instinct, some say, he relies on logic. As a result, Universal has had to depend on outside suppliers—Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment, Brian Grazer and Ron Howard’s Imagine Films—for its hits.

Nonetheless, MCA made an increasingly tempting takeover target. When Wasserman, who controlled nearly 20% of the stock through his own holdings and those of the Jules Stein Trust, went into the hospital in 1987 for minor colon surgery, the stock price jumped on the chance he might not recover. MCA’s board, which was dominated by insiders, adopted a “poison pill” provision that would flood the market with new stock if a takeover attempt was launched, but the ticker price only went higher. Realizing that once he was gone, the company would be fair game, Wasserman reportedly began to think of a sale. But there was another consideration as well. “I gather that sooner or later,” one former colleague says, “he had to sell for tax purposes.”

Almost from the beginning, tax law had been an obsession at MCA. The talent raids that turned CBS into “Paley’s Comet” at the end of the ’40s were accomplished largely through the lure of the capital gains rate—25 per cent, at a time when the top income-tax bracket was 77 per cent. A decade later, when MCA first offered its stock to the public—a mere 400,000 shares of 4 million—Fortune magazine concluded that Stein, who owned 1.4 million shares, was doing it to establish a market for estate-tax purposes. The offering was heavily oversubscribed, even though underwriters warned that the company would likely be operated as a “tax convenience” for the Stein family.

In 1990, when Michael Ovitz of Creative Artists Agency, acting as agent for Matsushita, went to Sheinberg with the idea of making a deal, Wasserman was talking merger with Martin Davis, chairman of Paramount Communications. As the Paramount talks collapsed, reportedly over the issue of Sheinberg teaming with Davis as co-CEO, the Matsushita discussions were picking up. Ovitz phoned Felix Rohatyn, an MCA board member and partner at Lazard Freres, MCA’s investment bankers. Matsushita enlisted another MCA board member—Robert Strauss, the former Democratic Party chairman, a longtime Wasserman friend whose Washington law firm worked for both Matsushita and MCA—to serve as counsel for both sides. Despite this apparent coziness, however, the only real points of contact were Ovitz, who kept the principals apart as long as possible, and Strauss, whose history with both parties provided a crucial inside channel.

Matsushita was so eager to retain Wasserman and Sheinberg that it invited them to set their own compensation. Other aspects of the negotiations suggest distrust, however—such as the discussions of price, which had started with Ovitz floating a figure of $75 to $90 a share. The negotiations stumbled badly when Matsushita’s offer came through at $60 in cash, plus an equity stake in the New Jersey TV station, now known as WWOR (spun off because foreign companies aren’t allowed to own U.S. broadcasting stations). Although MCA’s stock was languishing in the mid-30s at the time, thanks to the Persian Gulf crisis, it had traded in the $70 range earlier in the year. When MCA rejected the $60 offer, Matsushita made a $64 bid, which was also rejected. Then, after dinner at the ’21’ Club the night before Thanksgiving, Wasserman casually mentioned to Strauss that an extra two or three dollars per share might have done the trick.

The following Monday, after a weekend of intensive negotiations, Matsushita agreed to acquire MCA for $66 a share in cash, plus an equity stake in WWOR. But an alternative offer was made for MCA’s three largest shareholders: Wasserman, Sheinberg and David Geffen, who’d sold Geffen Records to MCA the previous spring for a 10% stake in the company.

Instead of cash, which means any profits on the transaction will be taxed as capital gains, this arrangement would give the men, tax-free, stock paying hefty dividends, but not redeemable for years. Geffen, whose massive holdings in MCA were hamstrung by restrictions, opted for the cash. Sheinberg did too. Only Wasserman chose the alternative.

It’s not hard to figure out why. Wasserman had acquired 5 million shares of MCA stock at an average price of just three cents per share. If he died holding it, his estate would face a tax bill so enormous that his heirs would have to flood the market with stock to pay it. If he sold out now, he’d have to hand the government about $110 million of his $327 million share. Either way, as Columbia University law professor Henry Paul Monaghan later pointed out in a brief filed on behalf of dissident shareholders, “he faced life’s twin certainties, death and taxes.”

“I’m sure that if Matsushita could have done something for him on the former, they would have,” says Roger Kirby, an attorney for the plaintiffs. “But, realizing that their achievements in science are not that great, they wisely focused their attentions on the latter.”

And so a new corporation was created, Matsushita Holdings, specifically for Wasserman. Holdings, a subsidiary of Matsushita, would become the real owner of MCA. In exchange for his MCA stock, Wasserman would receive preferred stock in Holdings paying a guaranteed dividend of $28 million a year, on top of the $15 million he’d be getting during the next five years from his new employment contract with Matsushita. Holdings was required to guarantee Wasserman’s investment with letters of credit from top banks. Wasserman’s ultimate collateral, however, was MCA itself. Should the banks fail, Wasserman could seize Holdings and appoint a new MCA board that could do anything necessary to get him his money.

All this notwithstanding, on the Monday the deal was to be signed, with champagne toasts and a satellite news conference at which Matsushita’s president would field questions about the $6.1 billion acquisition from company headquarters in Osaka, Wasserman and his attorney nearly refused to show up: He didn’t like it that one of the banks that had been lined up to issue his letters of credit was Japanese. An accommodation was made at the last moment, and the sale went ahead.

May 21, 1995

May 21, 1995