April 11, 2012

Some of the most intriguing innovations in storytelling these days are happening in the UK, where broadcasting networks, book publishers, and even newspapers have embraced the idea of creating immersive narratives that invite the audience to join in. The latest effort comes from Matt Locke, former head of cross-platform programming at Channel 4, who left television last year to start Storythings, a consultancy that’s been developing projects with top brands and media outlets. Storythings’ first project, released last month, is Pepys Road, an online story that ties in with the John Lanchester novel Capital, recently published by Faber & Faber.

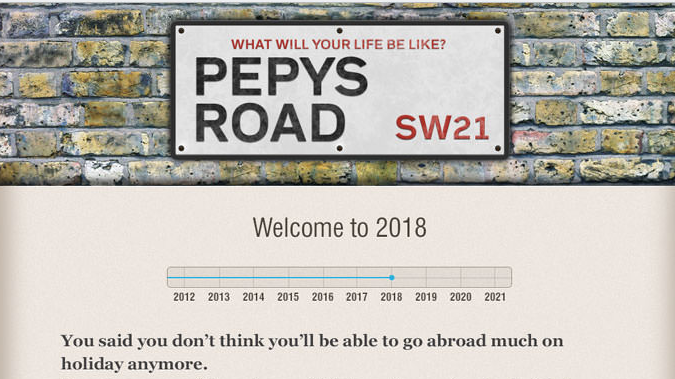

Capital documents the lives of characters on a fictional South London street as they deal with the fallout from Britain’s ongoing financial crisis. Pepys Road is designed to bring all this home to the reader. To experience Pepys Road, you go to the Web site, type in your date and place of birth and the place you live now, and wait for what happens next. Over the next 10 days, you get a series of emails containing, among other things, stories by Lanchester that demonstrate how you might be affected by the economic changes the next 10 years are expected to bring. The experience is immediate, immersive, and highly provocative. Here’s what Matt had to say about it.

Capital is a novel about the people who live on Pepys Road, but Pepys Road is all about what happens to you, the reader. Clearly these are meant to be complementary—but what does one give you that the other doesn’t?

The novel Capital illustrates how growing financial inequality has led to London being a city of social layers—classes of people who live close together, but whose lives don’t really connect in a meaningful way. When you read the book, you can’t help but think about your own life, and how your own network and activities are defined by similar economic and social segregation.

Talking to John Lanchester at the beginning of the project, we were discussing the “Lost Decade”—the period of stagnant or negative growth that most economists are predicting—and what it might mean for society. We felt that a lot of people feel a great amount of uncertainty about their future, and the future of their families, and that this was an interesting way to introduce people to the themes of the books.

If you’re trying to get people’s attention online, you have to think about what they are concerned about, or the information they value. The idea of telling the story of their life in this “lost decade” felt like something that is very much at the heart of the book, but also valuable as an exercise for users on a personal level. This is at the heart of online storytelling for me—how do you take people on a journey from their own questions and issues, which are the start of any journey online, into the storyworld you’re trying to create?

I gather you developed Pepys Road in tandem with James Bridle, who’s sort of a maverick within the UK publishing industry. What did he bring to the party, and how did you work together?

James has been producing really fascinating work and writing about books and digital technology for many years now, so I really wanted to work with him on a book project. Capital is partly about the invisible flows that affect our lives in the city – the flows of data, money and other information that influence where we live, who we meet and what we buy—and James has been producing some lovely online projects based around how we visualise and tell stories about data. I originally hired him right at the beginning, when we were producing ideas for Faber around a couple of titles, including Capital, and we had a few wide-ranging conversations about how we could join his interests in data and “new aesthetics” with the storyworld of Capital. From those early conversations, we developed the idea of a series of short narratives, and how we could punctuate these with a couple of “data illustrations” that use live data to illustrate how these invisible flows affect your life. We then brought a stellar team together, including Chris Thorpe, Kim Plowright, Dean Vipond and Phil Gyford, to work these early ideas up into the full project.

Books are generally written by one person, two at most. How important is collaboration in a project like this?

The collaboration with John was really important, as I wanted the online project to be a subtle “on ramp” into the work of Capital, and in particular, John’s writing. He’s an astonishingly good and prolific writer, and fortunately he loved the idea enough to make time to write 13 mini-stories for the online project. He was really interested in this way of working, and was completely across the way in which the mini-stories fitted into the whole user experience of the project. Its not incredibly complicated as a project, but I think its elegant—it has just enough complexity, but hopefully that doesn’t get in the way of people really appreciating John’s writing, and going on to buy and read the book.

You’ve mentioned that one of your inspirations was OhLife, the online diary-writing service. Is OhLife something you use yourself? How does it work, and how did it figure in coming up with Pepys Road?

OhLife is a really simple private diary service that sends you an email every day asking how your day has been. You respond by replying to the email, and it stores your diary entry, so you can use the service without ever actually visiting the site. It quickly becomes a habit, and I’ve kept a diary for longer with OhLife than anything I’ve ever used before, partly because it’s private, and partly because it plays this lovely trick of giving you an old diary entry at the beginning of each email. This moment of reflection is a really good spur to keep you writing your diary—it shows you the value of doing it, and helps you reflect on what you’ve done and where you’ve been in the past.

This kind of reflection was really important to Pepys Road, as I wanted people to think about how their lives might change in the future. I also wanted to create a longer attention pattern for the project—a lot of marketing focuses on creating one spectacular “hit” that you can instantly share, but little incentive to come back to the project after that initial visit. Capital is a big book, and I wanted the project to reflect the attention pattern of reading—a few minutes a day, every day, rather than the instant hit and share of most online content. So we borrowed two ideas from OhLife—the use of email to create a habit of reading in the stream of our daily digital activities, and the use of feedback to help people reflect on what they’re doing and have done in the past.

Aside from getting them to buy the book, how would you like Pepys Road to affect people?

The mini-stories that John has written for the project are really affecting, I think. Without us discussing it, he’s used the perfect tense online—the texts talk about “you” in the way that most Web services do, so the writing has that feel of online vernacular. They feel familiar, but they’re describing how the world might pan out, and what your position in it will be, so there’s something a bit uncanny about it. I hope that the stories make people think about the way our attitudes and lives might change in the next few years, and the paths our own lives will take. This is absolutely the feeling I got reading Capital, so I think Pepys Road is very much a part of that storyworld.

You were head of cross-platform development at Channel 4. What did you do there? Is it very different working with a book publisher?

Publishing has had a much sharper and more destabilising shift to digital distribution than TV, so the need to innovate and understand the new patterns of audience attention feel more urgent there. TV has been exploring digital for over a decade, yet most traditional broadcasters are still generating the vast proportion of their income from linear TV ads, sold according to sampled BARB or Neilsen data. The economics of broadcast has not been disrupted yet in the way Amazon has disrupted publishing economics in the last few years, so TV is still having fun playing around, but isn’t feeling the shift in its bottom line yet. The last 10 years I’ve spent in broadcasting have given me valuable experience from all the experiments and innovation we’ve had time to do, but it’s great working in publishing, where the feeling is that the change is happening *now*. I think there’s a magical figure of 20 per cent—when a traditional media company sees the amount of its bottom line income from digital reach 20 per cent, the industry goes into a different, more urgent, period of change. TV isn’t there yet, but publishing is. The music industry was there about five years ago, and the film industry is a few years away. The games industry is crossing that line at the moment.

I’m always getting asked if experiences like this—experiences that take you deeper into a story—will ever stand on their own, or if they will always be marketing tools for a movie or a book or whatever. What’s your take on this? Does it matter?

I don’t think it matters at all. I think of culture as something that begins when you first hear about it, and ends when you’re talking about your experience of the project with friends, so to call one element “the work” and the rest “marketing” isn’t that useful. When the cost of moving your attention from one piece of content to another is so small, we need to look at the attention curves around content, and how the work can reward and trigger certain kinds of attention patterns that help us tell the story.

This is what David Simon was doing when he created The Wire—telling a story that required a longer, more intense kind of attention than the usual CSI hour-long EP. It’s why Angry Birds is optimised for 10 minutes of play at a time. We’re seeing lots of different kinds of attention patterns that are now viable as media devices have made every minute of the day a possible cultural moment. I think we’re just beginning to discover what kinds of attention patterns people are willing to fold into their daily lives, and the kinds of economics that will support them.

This isn’t just a recent phenomenon. When the Telefon Hírmondó, the Budapest “telephone newspaper,” first used the telephone as a broadcast network in the late 19th century, it faced the problem of how to schedule content for audience’s attention across a 12- or 24-hour period for the first time. It decided to use blocks of 1 hour/30 minute/15 minute content, a format that we still use in TV over a century later. Every cultural form has been created around the possible attention patterns for its audience—how long they can comfortably sit in a theatre, how big a book you can carry, etc.—and we’re just beginning to discover what these are for these new forms. I’m currently writing a book on the “history of attention,” looking at how earlier cultural forms were shaped by the attention patterns of the time, and what we can learn from the interplay of artist, economics and audience that create the dominant patterns at various times in our cultural history.

More than a decade ago, Electronic Arts created Majestic—a fictional game that bled into your life. It didn’t work, largely I guess for economic reasons. Do you think something like it could work now?

Again, I think there are some very mature and mainstream patterns of attention in our daily lives that you can use to tell stories. Where a lot of alternate reality games and immersive stories fail is in asking for too much attention, and not being aware of the kinds of patterns that people are willing to give to new forms of stories. Only a tiny proportion of the audience is willing to give up their daily routine to a story that could pop into their lives at any moment and demand their attention. I think it’s better to really look at people’s patterns of attention, and think about how you can work with the grain of this experience, rather than trying to disrupt it.

Disruption, or trying to get audiences to follow a new pattern of attention, is extremely hard, and should be used only for a specific, visceral effect in an online story. It’s the digital equivalent of Brechtian breaking of the “fourth wall” in theatre—you need to really demonstrate to the audience that you understand the aesthetics and vocabulary of their context before you break it, otherwise is just annoying interruptions instead of drama.

You’ve written about “spiky networks” as a defining aspect of digital culture. What do you mean by that? And what are the implications for anyone trying to make an impact?

I think that Bill Wasik’s And Then There’s This is the best definition of what spiky networks are—that’s a fantastic book about new attention patterns around digital culture. In short, spiky networks are what happens when there is very little economic, technical or cultural barriers to audiences switching their attention from one cultural object to another. In the days of analogue media, where the choice of content was severely limited, and the act of switching attention had economic or physical costs—buying another newspaper, or physically switching channels. This created an era of abnormally stable attention patterns, and cultural forms developed to take advantage of this.

We are now in an age of spiky attention, where no platform, channel, or artist has a monopoly on our attention, so everyone has to work harder to develop relationships and habits in the audience that will keep their attention. It is characterised by huge spikes of attention, as our cultural networks temporarily align to give large amounts of traffic to a particular cultural object, but this attention will shift in the next moment to a new object, and keep doing so. The challenge now is how to build loyalty and retention of attention, rather than one-off viral hits. This is what games companies like Zynga understand, why YouTube has redesigned around channels rather than viral videos, and ultimately why the big four—Apple, Amazon, Google and Facebook—are focusing on building ecosystems rather than platforms.

In the 20th century, scale was technologically and economically really hard, but if you achieved it, you had a monopoly on attention and longevity was the reward. In the 21st century, scale is not technologically or economically hard. It’s hard for different reasons, mainly to do with aligning taste networks to get spikes of traffic, but you will never have the same monopoly on attention, and so longevity is hard. If scale was the problem that mass media had to solve in the 20th century, then retention and longevity is the problem mass media has to solve in the 21st century. If McLuhan were alive today, he’d be writing about archives, privacy policies and algorithms that align our taste profiles. These are the factors that define how we share culture today.

Comments

Comments are closed here.