August 27, 2013

I’ve long been a fan of David Carr’s media column in The New York Times, but yesterday’s was a landmark. In a piece headlined “War on Leaks Is Pitting Journalist vs. Journalist,” Carr takes on the bizarre—there’s no other word for it—attacks on WikiLeaks and The Guardian‘s Glenn Greenwald for their role in the release of classified documents by former PFC Bradley Manning and former NSA contract employee Edward Snowden. There’s only one way I can see to explain the kind of treatment they’ve been getting: as a sign of the identity crisis that is overtaking conventional journalism in a time of threat.

Both Bradley and Snowden were acting very much in the tradition of Daniel Ellsberg, whose release of a top-secret US government report on Vietnam some four decades ago exposed a systematic pattern of lies to both Congress and the public. Though he was charged with crimes by the government, Ellsberg was lionized by the media, and The New York Times won a Pulitzer for reporting his revelations. Today, however, the story is very different. Witness Greenwald’s appearance on Meet the Press, when, as Carr points out, he was asked why he himself should not be charged with a crime for having “aided and abetted” Snowden. And that was only the start of it.

A number of established journalists have made a point of going after Greenwald—most notably Jeffrey Toobin of The New Yorker, who distinguished himself on Anderson Cooper 360° last week by comparing Greenwald’s partner, who had just been detained for nine hours at Heathrow on suspicion of terrorism for possibly carrying secrets to the Guardian reporter, to a drug mule. Toobin railed against “the rampant lawlessness that was behind these stories,” apparently forgetting that Ellsberg didn’t exactly pick up the Pentagon Papers in a Defense Department bookstore. And when it comes to WikiLeaks—whose founder, Julian Assange, has been holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy in London for 14 months now, dodging a rape charge that may or may not be trumped up—the gloves really come off. Witness Michael Grunwald of Time, who a few days earlier tweeted, “I can’t wait to write a defense of the drone strike that takes out Julian Assange”—a remark that’s chilling on several levels, starting with the suggestion, however jocular in intent, that a drone strike against Assange might actually be in the offing.

The same pattern was in evidence three years ago when Rolling Stone published the exposé that ended the military career of Gen. Stanley McChrystal, then commander of US forces in Afghanistan. As Mark Leibovich reminds us in This Town, his take-no-prisoners depiction of life forms inside the Beltway, Michael Hastings, the journalist who wrote the McChrystal story, came in for the same sort of attack. CBS correspondent Lara Logan went out of her way to cast doubt on Hastings’s professionalism: “I know these people,” she announced on CNN’s Reliable Sources, referring to McChrystal and the aides Hastings quoted in his story. “They never let their guard down like that. To me, something doesn’t add up here.” Sure, Hastings had just broken the biggest story in Washington—but he must have broken the rules to do so. He wasn’t a journalist—or at least, not a “reputable” journalist.

So, what gives?

Carr nailed it when he wrote that people like Greenwald “aren’t what we think of as real journalists. Instead, they represent an emerging Fifth Estate composed of leakers, activists and bloggers who threaten those of us in traditional media.” Or as GigaOM‘s Mathew Ingram put it in response to Carr’s column, “what we are seeing is an immune-system response from the journalism establishment.”

For context, Ingram points to a 2010 Clay Shirky essay on the shock 20th-century journalists generally feel when confronted by the realities of participatory media:

Part of the conceptual simplicity of traditional media came from the near-total division of the roles between professionals and amateurs, and the subsequent clarity that division provided. Reporters and editors (and producers and engineers) worked “upstream,” which is to say as the source of the news. . . . Meanwhile, we, the audience, were “downstream.” We were the recipients of this product, seeing it only in its final, packaged form. We could consume it, of course (our principal job), and we could talk about it around the dinner table or the water cooler, but little more. . . . If we wanted to put our own observations out in public, we needed permission from the pros, who had to be convinced to print our letters to the editor, or to give us a few moments of airtime on a call-in show.

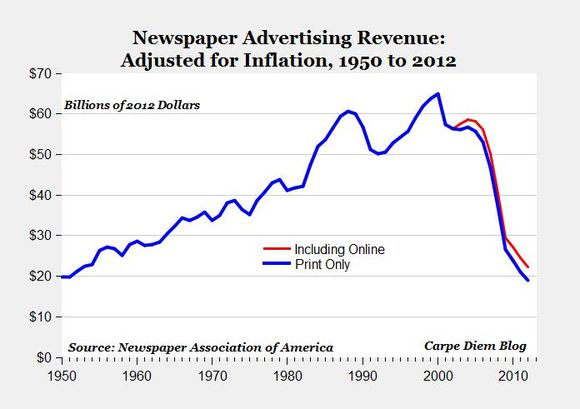

That world has been obfuscated out of existence by the kind of blur that David Shields describes in Reality Hunger. And even as digital media are obscuring the distinction between journalist and reader, producer and consumer, professional and amateur, they are gutting the institutions that employ those professionals. The American Enterprise Institute’s Carpe Diem blog recently reported that in inflation-adjusted 2012 dollars, newspaper ad revenues have fallen from a high of $65 billion in 2000 to $22 billion last year (if you count online advertising). Magazines have fared little better. Is it entirely by coincidence that the assaults from Toobin and Grunwald come in the same month that, according to Felix Salmon’s analysis for Reuters, the Washington Post Company essentially gave Jeff Bezos $83 million to take The Post off its hands?

The great irony here is that the journalists who are attacking Greenwald et al. seem themselves to have forgotten what real journalists do. Investigative reporting is not about observing legal niceties and protecting government secrets. It’s about letting people know what the hell is going on. Unless the media institutions that still survive in this country remember that, no one will particularly care what happens to Glenn Greenwald.

Comments

Bob Kohn

- August 28, 2013

And let's not forget how the professional journalist community took down James O'Keefe, whose 60 Minutes-like hidden video pieces took down the scandalous Acorn organization among other things. http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_O'Keefe