![]()

December 30, 2011

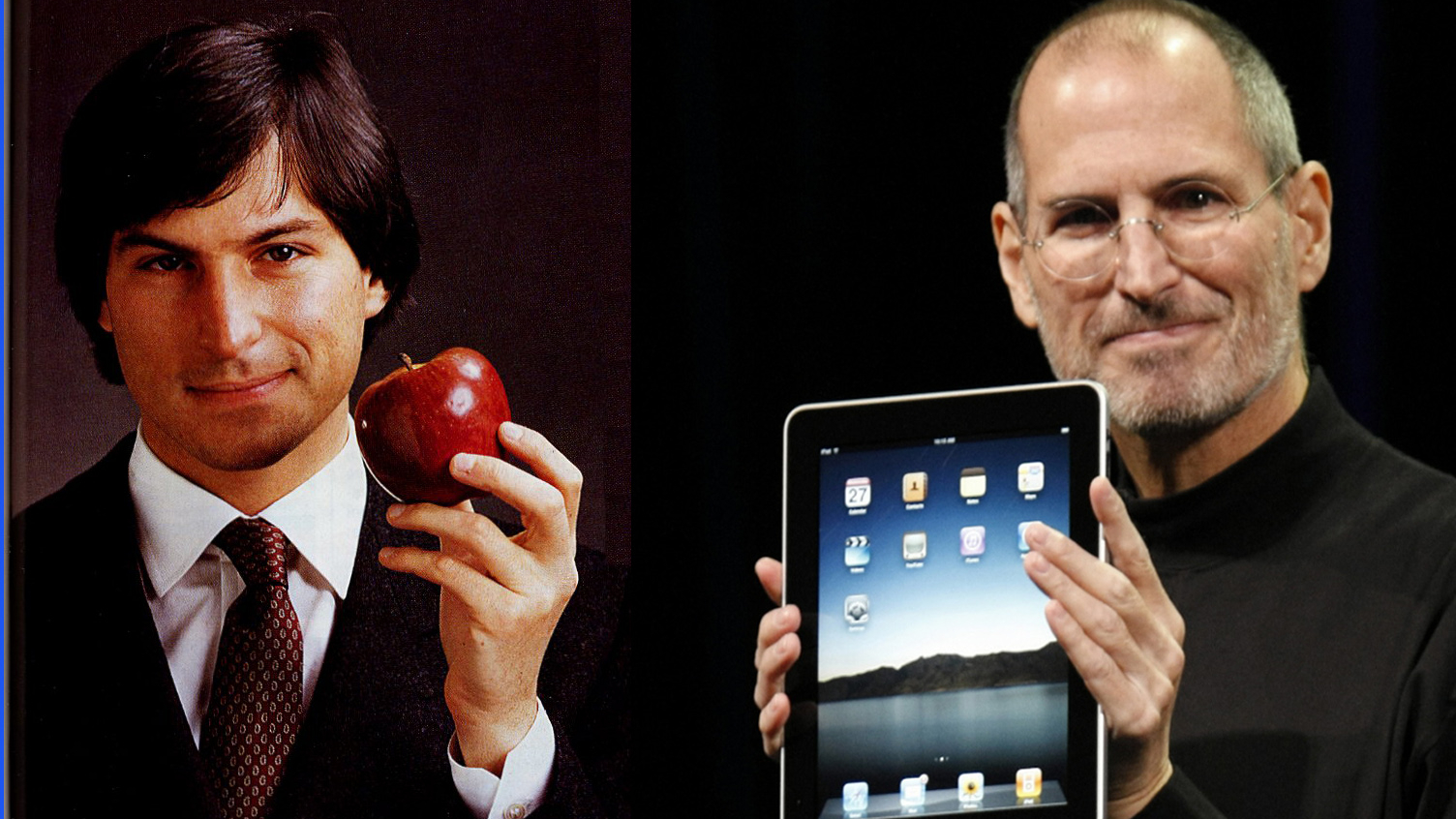

Earlier this week I was asked to appear on Bloomberg Rewind, the daily TV recap hosted by Matt Miller, to talk about the legacy of Steve Jobs. Having recently finished the Walter Isaacson biography, and having a few thoughts of my own on the subject, I took it as an opportunity to grapple with a question that’s bothered me for some time: Not just what Jobs left behind, but what made him great—and why that was so hard for most people to see until his business success made it so blindingly obvious.

Jobs’s accomplishments are fairly easy to summarize. Let’s see: he reinvented what a personal computer could be, what an animated movie could be, what a music player could be, what an online music store could be, what a real-world tech store could be, what a mobile phone could be, what a digital tablet could be—and by many accounts he was well on his way to reinventing what television could be when he died. In the process he not only reshaped the computer business, the music business, the mobile phone business, and the retail business; he also helped lay the groundwork for the kind of deep media experiences that are transforming the way we tell stories. Along the way he engineered a reverse takeover of not one enterprise but two—Apple, when it bought NeXT in 1997 and he ended up in control, and Disney Animation, when Disney bought Pixar in 2006 and the Pixar people took control. Not bad.

The key word here is “reinvent.” Jobs didn’t dream up any of the gadgets that made Apple so successful. He—and his people—refined them. Time and again they took ideas that were in the air, or at least in the lab, and figured out what was missing from all previous iterations. Then they re-imagined and realized them as (to borrow a phrase from my colleague Steven Levy) the perfect thing. Or as close to perfect as he and his team could humanly get.

It’s easy to look back now and say the man was a genius. It’s much harder to embrace the qualities that made him that way. Having covered the 29-year-old Jobs’s ouster from Apple in West of Eden, I can report that the hagiography that accompanied his death this fall had its flip side in the near-exultation that accompanied his forced exile in 1985. John Sculley, the CEO who kicked him out, was greeted at the time as Apple’s savior—a bit prematurely, as it turned out. Jobs was the bratty entrepreneur who had to be sacrificed so Sculley could assume the mantle of visionary even as he churned out widgets.

As I read Isaacson’s solid and insightful account, I jotted down a whole laundry list of qualities that contributed to Jobs’s eventual success. Then, taking to heart Jobs’s insistence on reducing everything to its essence, I stripped those down to three interlocking attributes. If somebody could teach these in business school, the world would be a lot better off.

1. Passion

Jobs took everything to extremes, from his vegan diet to his insistence on good design to the brutal honesty he dealt out to employees (and occasionally to journalists: the dressing-down he gave me when I stepped over the line he’d drawn for our interviews at NeXT was one of the most frightening moments I’ve ever experienced). But the point was, he cared. No, he wasn’t a nice guy. Yes, he could be kind of crazy. But if you challenged him and could persuade him you were right, he would respect you for it.

Much has been made of Jobs’s “reality distortion field.” Let’s just say it was a very useful device, not just for casting a spell on his audience but for pushing people to do what everyone else considered impossible. Isaacson describes an exchange between Jobs and Wendell Weeks, the CEO of Corning, over “gorilla glass,” the super-strong material Jobs wanted for the iPhone. Corning had invented it in the 1960s but quickly abandoned it for lack of a market. Now Jobs wanted as much as they could manufacture in six months. Weeks said it couldn’t be done. “Don’t be afraid,” Jobs responded. “Get your mind around it. You can do it.” He did.

I saw the same quality at work when I interviewed members of the original Mac team and the people who left Apple with him to start NeXT. They weren’t there because Jobs was a great manager. In fact, he was a horrible manager. But he was a born leader. He didn’t manage people, he challenged them. And though they’d lived through his tirades more than once, those who met the challenge were ready to follow him anywhere—even to NeXT, which at the start was little more than an idea in search of a business plan.

2. Integrity

One of Isaacson’s signature anecdotes involves a childhood lesson Jobs learned from his father, Paul Jobs. When Steve was a kid, the elder Jobs built a fence around the house, and he took just as much care with the parts no one would ever see as he did with the parts that would be visible to the world. This was a lesson Jobs sometimes took to extremes, as when he insisted on painting first the Macintosh factory and then the NeXT factory a pure, pristine white. The same impulse drove him to reject Steve Wozniak’s initial design for the circuit board for the Apple II because the lines weren’t straight enough. But it also meant that the products he approved had an honesty and integrity you could appreciate, even if you couldn’t actually see them.

There are countless stories about Jobs’s drive for perfection, many of them involving his passion for good design. Most CEOs in the tech world—make that most CEOs, period—view design as a frill, not as an integral product feature. To Jobs, it trumped even engineering. The essence of good design, by his definition, was simplicity, because simplicity makes for elegance and ease of use. Which leads us to his third key quality:

3. Focus

To me, one of the most fascinating periods of Jobs’s hugely eventful life is his return to Apple in 1997. After selling NeXT to a desperately diminished Apple for its operating system, he more or less walked in and assumed power. And with no one around to tell him what not to do, he did much of what he’d wanted to do in 1985, when Sculley, the board, and the company’s vice presidents forced him out. One of the first things he did was to focus the product line, which had grown bloated and incoherent, on four core offerings. There would be a laptop and a desktop for the consumer market, and a laptop and a desktop for the professional market. And that was it.

The same focus Jobs brought to the product line, he brought to the products themselves. He pushed his team to strip away anything extraneous and concentrate on the essence of whatever they were working on. What was its overarching purpose? Toy Story, the breakthrough picture that established Pixar as a force in animation, proceeded from the realization that a toy’s purpose is to make kids happy. The iPhone owed its success in large part to Jobs’s realization, very late in the design process, that it was all about the display—the part that showed you what you could do. Everything else was superfluous.

Similarly, Jobs insisted on identifying and eliminating the shortcomings of previous iterations of whatever product he was developing. What’s missing? What sucks? There were lots of digital music players on the market when the iPod came out. The iPod blew them all away (not to mention those that followed, like Microsoft’s ill-fated Zune) because it was designed for one simple purpose—to make it easy to listen to your music. And because he was so passionate, Jobs wouldn’t rest until it really was easy—until you could get to any song on the device in no more than three clicks.

With focus comes a certain clear-headedness about what you want to achieve. This is a big part of what makes Apple worth more than $376 billion on the market today, compared to $1.6 billion when he took over in 1997. Yes, he was a master marketer—anyone who’s ever watched an Apple product introduction can tell you that. But what mattered more, what kept his reality distortion field from degenerating into mere hype, was that his products were so good they marketed themselves. This idea is so important it’s become the subject of an entire book—Baked In, by Alex Bogusky and John Winsor. But getting there requires passion, integrity, and focus. Anything else is just extraneous.

Comments

Comments are closed here.