An architectural rendering of Poplar Forest’s south front, c. 1819. Credit: The University of Virginia Special Collections Library

THOMAS JEFFERSON’S RETREAT at Poplar Forest has never been easy to find. That’s the way he wanted it: this was his escape from Monticello, where his retirement was interrupted by a ceaseless procession of friends, acquaintances, strangers and tourists, some of them so transfixed by his celebrity that they lurked in the hallways hoping to catch sight of him as he moved from room to room. At Poplar Forest, eighty miles away in the farm country outside Lynchburg, he could read the classics, write to his friends, and spend time with his grandchildren. Other visitors were not encouraged.

Today, Jefferson’s little-known hideaway is the site of a full-scale archaeological investigation. Working under the aegis of a nonprofit corporation which purchased the.property in 1984, when developers were pawing at its gates, a team of historians, archaeologists, and architects is digging up the lawn and pulling down the plaster to determine just what Jefferson constructed there. To the untrained eye, Poplar Forest looks like a typical Virginia plantation house—red brick, white columns, boxwood garden—with a few puzzling eccentricities, like its octagonal shape and the two circular mounds of earth that flank it. The picture that’s emerging, however, is of a miniature Palladian villa in a formal neoclassical setting, the rigid geometries of which contrast sharply with the English romanticism of Monticello’s undulating walkways and naturalistic vistas.

Researchers have pored over dozens of letters between Jefferson and his builders—hired workmen and skilled slaves sent down from Monticello—but the paucity of visitors means there are few descriptions of the completed house. Even worse, a fire in 1845 seriously damaged the interiors and the roof; in the quick-and-dirty remodeling that followed, the farm family that bought the place from Jefferson’s heir added dormers and an attic and eliminated many features only now coming to light. In Jefferson’s bedroom, for example, “ghost” marks on the underlying brick indicate not just the location of the original baseboard and chair rail but the existence of an alcove bed that divided the room, much as the alcove bed at Monticello separated his bedroom from his study.

Jefferson began building his retreat in 1806, just as Monticello was nearing completion after 37 chaotic years of construction and reconstruction. He’d inherited Poplar Forest, a 4,800-acre plantation, from his father-in-law in 1773, and when the British raided Charlottesville in 1781 he took refuge there. He used the occasion to write his Notes on the State of Virginia, which included a remarkable attack on Tidewater colonial architecture: “It is impossible to devise things more ugly, uncomfortable, and happily more perishable.”

Jefferson’s contempt for colonial architecture was tied to his politics. Neoclassicism, an emerging style spurred on by the newly invented science of archaeology, held out the promise of abstract beauty and universal truth. By rejecting the bankrupt traditions of Europe, the new republic could pattern itself after the models of antiquity—something Jefferson did quite literally when he designed Virginia’s new capitol in Richmond after the Maison Carrée in Nîmes. At Poplar Forest, the mathematical roots of these models are made explicit.

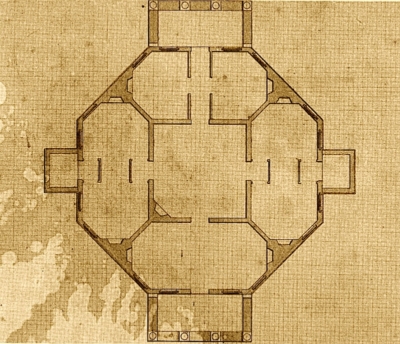

The floor plan, with the south front at bottom.

Here, in a landscape of gently rolling red clay hills, Jefferson’s lifelong preoccupation with the octagon reached its fullest expression. Octagons and semioctagons recur throughout Monticello, reflecting his love of light and air as well as the neoclassical fascination with circles and octagons as ideal Platonic forms. But this time Jefferson went further. The house at Poplar Forest was precisely oriented along a north-south axis and constructed as an octagon with sides 22 feet long. At its center, lit by a skylight and reached through a tunnel-like hall from the north portico, a twenty-foot cube served as his dining room. Octagonal bedrooms flanked it on the east and west, while the octagonal drawing room to the south with its enormous triple-sash windows opened onto a second portico overlooking a sunken bowling green.

According to landscape historian C. Allan Brown, however, the quest for order was not confined to the house itself. Brown, a consultant to the restoration effort, maintains that the house was merely the centerpiece of a far larger geometric composition. Its placement atop a rounded knoll made it an ideal spot to experiment with the pure geometry of the circle, and that’s what Jefferson seems to have done.

Documents indicate that the fifty-foot house was circumscribed by a 540-foot circular lane lined on both sides with mulberry trees. Inside this circle an octagonal fence apparently ran 200 feet on a side, and the lawn inside that was quartered by landscape features that extended from the house like the arms of a cross. On the south side there’s the rectangular bowling green. On the north side, an approach road runs directly toward the house, crossing the circular lane and culminating before the portico in a fifty-foot circular carriage drive which encompasses a boxwood labyrinth. To the east and west are the ornamental mounds, planted (if Jefferson’s instructions were followed) with concentric rows of willows and aspens and linked to the house by double rows of mulberry trees. Beyond the mounds are domed octagonal privies which look like miniature temples.

There are flaws and question marks in this composition: Jefferson’s letters make no mention of the carriage drive, for example, and in 1814 he apparently had one row of mulberries pulled down to make way for a colonnaded wing of outbuildings (now destroyed) between the house and the east mound. Exactly what Poplar Forest looked like in his day will take archaeologists years to determine. But the current evidence suggests a villa that recalls, on a modest scale, the French neoclassicism of Ledoux and Boullée, whose work Jefferson saw in Paris in the 1780s.

Brown suggests a further link, to the mandala—the mystical circle that recurs throughout human experience, from the rituals of Tibetan Buddhism to the drawings of the mentally disturbed. Mandalas represent wholeness; Jung saw them as a spontaneous attempt by the mind to heal itself. Certainly it’s no accident that the pure geometry of neoclassicism flourished during the chaos of the French Revolution, and it makes sense that Jefferson would turn to it in his waning years, when instead of the dignity and respect he was entitled to he suffered the degradation of shameless curiosity-seekers and looming financial ruin. Sitting at his octagonal dining table in his cubical room in his octagonal house on its octagonal lawn within its circular roadway, with the sun shining down from above, he may finally have found the harmony that eluded him elsewhere. ◆

The restored south front today.

November 1, 1991

November 1, 1991