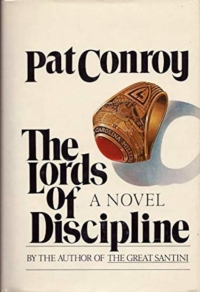

PAT CONROY does not like military academies. A 1967 graduate of the Citadel, he has written here about a fictional “Carolina Military Institute” that combines some of the more quaint and murderous aspects of the Citadel, West Point, and Virginia Military Institute. Set in the Charleston of his own senior year, The Lords of Discipline is Conroy’s rendering of life in an institution whose mission is the making of men — or rather, the making of men and the breaking, deliberate and absolute, of those boys who fail to measure up.

What Conroy has achieved is twofold; his book is at once a suspense-ridden duel between conflicting ideals of manhood and a paean to brother love that ends in betrayal and death. Out of the shards of broken friendship a blunted triumph emerges, and it is here, when the duel is won, that the reader finally comprehends the terrible price that any form of manhood can exact. Conroy’s personal triumph is in conveying all this in a novel that virtually quivers with excitement and conviction.

The Lords of Discipline, by Pat Conroy. Houghton Mifflin, 499 pages

October 19, 1980

October 19, 1980