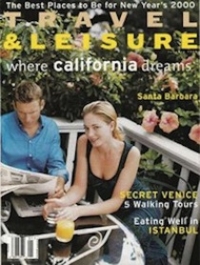

In the Santa Ynez Valley

IT’S A STARRY NIGHT, and I am sitting in an ancient ranch house tucked deep in the Lompoc hills, two or three miles down a dirt road from El Camino Real, the purported route of the padres. The house, set beneath a spreading oak tree with a pickup truck out front, is low and rambling in the old California style, its simple board-and-batten siding painted white, its interior a warren of rooms filled with the accumulated books and portraits of several generations. Around us lie the 10,000 acres of Rancho San Julián, one of Santa Barbara’s original land-grant ranchos. I’m visiting my friend Marianne Partridge, an ex-New Yorker who edits the weekly Santa Barbara Independent, and her husband, Jim Poett. His family has owned this ranch since 1837, when California’s Mexican governor granted it to the family patriarch, Don José Antonio de la Guerra y Noriega, commander of the Presidio of Santa Barbara. We are talking about the land.

Sooner or later, all conversation in Santa Barbara turns to the land. Ninety miles northwest of Los Angeles, resting between the Santa Ynez Mountains to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south, Santa Barbara is where the L.A. sprawl stops. Beyond, spreading across the county, are some 40 land-grant ranchos on the order of Rancho San Julián, their vast acreage unspoiled by strip malls or tract houses. As Marianne recalls how Jim’s aunt rode the 35 miles east to Santa Barbara on horseback for the city’s first annual Old Spanish Days Fiesta in 1924, 12-year-old Justin Poett starts to tell me about a family trip to Spain, where Don José was born in 1779. “And he lived in a castle!” the boy cries excitedly.

Sooner or later, all conversation in Santa Barbara turns to the land. Ninety miles northwest of Los Angeles, resting between the Santa Ynez Mountains to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south, Santa Barbara is where the L.A. sprawl stops. Beyond, spreading across the county, are some 40 land-grant ranchos on the order of Rancho San Julián, their vast acreage unspoiled by strip malls or tract houses. As Marianne recalls how Jim’s aunt rode the 35 miles east to Santa Barbara on horseback for the city’s first annual Old Spanish Days Fiesta in 1924, 12-year-old Justin Poett starts to tell me about a family trip to Spain, where Don José was born in 1779. “And he lived in a castle!” the boy cries excitedly.

Castles in Spain are the proper reference point for Santa Barbara, a city that still fancies itself in the land of long ago and far away. Settled by Spanish soldiers like Don José and Yankee traders like the Poetts, the city became a playground for the Hollywood elite, who still find it as delightfully unreal as anything in Los Angeles—and considerably more pristine. Ever since the 1920’s, when nostalgia for the days of dolce far niente took root in earnest, Santa Barbara has been the primary locus of the California myth, the vision of California as a golden land, bountiful and enchanted. The Chumash, the Native American people who settled in this area before the Spanish, had their own word for such a myth: anacapa, mirage. To succumb to Santa Barbara is to recall an idyll that never was—but not to succumb is unthinkable.

I am here to reclaim the mirage. for years i’ve been coming to California as a reporter covering Hollywood and Silicon Valley; now my assignment is to daydream. To nourish my reveries, Marianne has recommended I stay at the Alisal Guest Ranch & Resort—10,000 acres in the Santa Ynez Valley, just across the mountains from Santa Barbara and the coast. The Alisal lies beyond the lazy Santa Ynez River on a lane lined with towering sycamores, flanked by a row of bungalows and a horse pasture with a forested ridge beyond. The property runs from the river to the summit, about four miles away, where it borders the Reagans’ Santa Barbara hideaway, Rancho del Cielo.

The term for the Alisal is low-key. Known as Rancho Nojoqui when it was granted to Raimundo Carrillo, whose brand now adorns its china as well as the flanks of its 2,000 cattle, the Alisal has been taking in guests since 1946. Doris Day came in the fifties, and Clark Gable was married in the library. But these days the place caters largely to families and doesn’t cause a blip on the glamour meter. It has the usual resort amenities—golf, tennis, swimming, and the like—but the real attractions are the land and the horses.

Thoroughbreds were raised on the Alisal in the 1920’s and 30’s, but now the stables hold mainly quarter horses, bred to handle cattle. “People I taught to ride as kids still come here,” says Jake Copass, the Alisal’s cowboy poet, a wiry wrangler who started working at the ranch in 1946. “Now I’m going to their kids’ weddings.”

At 9:30 in the morning, with the clouds rising off the mountains after yesterday’s steady rain, I head over to the corral and clamber onto a gelding named Cody. I ride into hills little changed from Don Raimundo’s day. Live oaks, valley oaks, and sycamores, their limbs hung with ghostly gray treebeard or bushy with mistletoe, punctuate the grassy hills. White-tailed deer graze in the shade; red-tailed hawks soar overhead. By a stream a wary squirrel looks out for coyotes. A flock of blackbirds swoops out of a tree to pick seeds from the hay that’s been left for the horses. Cattle graze on a hillside where golden eagles nest.

The mountains beyond me—part of a range that begins at nearby Point Conception and runs across the state to the Mojave Desert—mark the boundary between northern and southern California. Although Santa Barbara enjoys the warmth and opalescent skies of the Southland, here in the Santa Ynez Valley, on the northern flank of the mountains, we could as well be in the golden hills of the San Francisco Peninsula. The valley goes on like this for another 15 or 20 miles, until it gives way to the wilderness of the Sierra Madre. There are towns, but except for Los Olivos—a dusty country crossroads (population 900) with more BMW’s than one might expect—they have little to recommend them. This is horse country, wine country, and Hollywood country.

Michael Jackson’s ranch is just outside Los Olivos; Fess Parker, the onetime Davy Crockett star, owns a nearby winery that makes a well-regarded Chardonnay and is popular with tourists. There are other big wineries in the valley, but that’s not what I’m after. So after lunch the next day at Los Olivos’s Side Street Café, an artsy, homey establishment in an old tin-sided building, I head up Foxen Canyon Road, a two-lane blacktop that lies between a gentle fold of hills. In 15 minutes I come to a weathered barn with a hand-lettered sign out front: foxen open. Of the 30-odd wineries in Santa Barbara County, Foxen Vineyard is one of the best. Standing at its rustic counter, sipping earthy yet silken Pinot Noirs while gazing at a vineyard set behind a picket fence, I realize what wine making is all about: farming, and alchemy.

Up the road is Rancho Sisquoc, a 37,000-acre cattle ranch whose vineyard is among the oldest in the county. I walk into an unpainted shed and take my place at an ornate Victorian bar. “This thing is highly historical, whatever it is,” quips the wine maker, Carol Botwright, a young woman whose blue jeans and straight, shoulder-length hair give her the look of a perpetual grad student. Pouring a lush and fruity Sauvignon Blanc, she talks about life on the ranch: It’s nice to be able to walk to work, though it can get a little dicey with the grizzly. She keeps pouring. Eventually, cradling a glass of Sisquoc’s delectably smoky Meritage blend, I wander to the doorway. There are a half-dozen cars in the unpaved lot, and beyond that, nothing but grazing lands ringed by mountains that shine golden in the late afternoon sun. I begin to think: Maybe it isn’t a mirage…

Mission Santa Barbara

THE CALIFORNIA MYTH dates to the 16th century, when Hernán Cortés discovered the place and—inspired by a popular tale of a golden isle inhabited by Amazons riding winged griffins and ruled by a Queen Califia—named it California. In the story the Amazons were converted to Christianity, and when the Spanish finally settled the area two centuries later, they set about accomplishing this in fact. Mission Santa Barbara was one of the richest and most powerful in the province, until the missions were secularized in 1834—the padres cast out, their ranchlands seized by the Mexican government and granted to local notables such as Don José de la Guerra.

What happened next was captured in Two Years Before the Mast by Richard Henry Dana, who arrived in 1836 as a young officer on a Boston trading ship: sober Bostonians, beguiled by the easy pleasures of California living and by the ranchers’ daughters ripe for marriage, cast off their black frock coats and dour Calvinist religion to embrace sun and wine and pope. Which is why, if you go to mass at the mission, you’ll find not just laborers and businessmen but handsome matrons of an unmistakable New England cast, with high cheekbones and long blond hair swept back in black velvet ribbons.

Mission Santa Barbara looks ghostly in the early morning fog, its swaying palms and pink-domed bell towers materializing and dematerializing in the mist, its walled cemetery thick with musk as bird-of-paradise bursts forth beneath spreading magnolias. “Anacapa,” I murmur to myself as I wander among tombstones chiseled with names like Vail and de la Guerra and Orena, names of the Spanish-Yankee dons who once ruled here.

At the Santa Barbara Historical Society, I pause before a photograph from the first Old Spanish Days Fiesta. It shows Jim Poett’s aunt in flowing white skirts and black lace mantilla on the patio of Don José’s town house, the Casa de la Guerra. The 1924 Fiesta signaled the city’s embrace of its Spanish colonial heritage—never mind that early Santa Barbara had in fact been a ramshackle outpost, or that several of the outlying ranchos were hideouts for bloodthirsty robbers like Salomon Pico (inspiration for the mythical Zorro), who’s said to have made a necklace of dried gringo ears from the severed heads of travelers during the Gold Rush era. In 1930 another celebration was added to the calendar: the annual ride of Los Rancheros Visitadores, costumed horsemen re-enacting a long-forgotten ritual of the spring roundup. “Actually there is something rather pathetic about the spectacle of these frustrated businessmen cantering forth in search of ersatz week-end romance,” groused a critic, “evoking a past that never existed to cast some glamour on an equally unreal today.” No doubt—but as with Zorro, the brutal bandido transformed by Hollywood into a chivalrous aristocrat and defender of the weak, the spectacle fills a need.

Stroll through El Paseo, the 1924 shopping arcade that winds around the restored Casa de la Guerra, and you sense what that need is. Just off busy State Street, El Paseo is a narrow pedestrian alley that leads to a maze of shops, some grand, some tiny, each a surprise. Eventually you end up at the Wine Cask, a big, stylish restaurant with soaring white walls and a beamed ceiling. Just beyond its patio lies one of the best wine shops in California. Part shopping mall, part historic preservation project, El Paseo plays to the fantasy that there can be continuity in an increasingly disjointed world. As does Santa Barbara.

BY THIS TIME I’ve given up the Santa Ynez Valley for Montecito, in the foothills east of Santa Barbara. Until a century ago, Montecito was an unassuming country village. Then industrialists and meat-packers from back East—Armours and Fleischmanns and du Ponts—began to line its winding lanes with sumptuous gardens and villas, transforming it into an American Riviera. There are two extraordinary hotels: by the shore, the Four Seasons Biltmore, which is sprawling and public; and in the mountains, the San Ysidro Ranch, which is small and secluded.

After driving up a series of narrow lanes walled in by oleander hedges and punctuated by massive stone gateposts, I find myself at the San Ysidro, which bears little resemblance to the Alisal or to any other ranch known to man. Once it was a rancho like all the others, but it was turned into a resort in 1893. By the thirties it had become a hideaway for Hollywood stars—Bing Crosby, Groucho Marx, Gloria Swanson—and a favorite of traveling Brits like Somerset Maugham. It’s easy to see why.

With 21 cottages scattered among hundreds of acres of lawns and gardens high above the Pacific, the San Ysidro feels languorous and luxe. The rooms, some cozy, some grand, are sumptuous in an understated way, with private terraces, Frette linens, a stack of firewood by the door, even your name posted outside—or not, if you prefer. “This used to be the spot for assignations,” observes a Hollywood honcho who lives nearby. “But now you have to go to Big Sur to get away from the paparazzi.”

That’s because Montecito is practically a Hollywood suburb. Director Ivan Reitman just built a mansion amid the formal gardens of the old Armour estate; Michael Douglas, Steve Martin, Jeff Bridges, and Robert Zemeckis all have houses in the area. Many film people live here year-round, especially those who don’t want their children in a school where other kids are writing screenplays and reciting the weekend grosses. How long until Montecito’s schools are just as bad is anyone’s guess.

Still, on a Saturday morning with the sun glinting off the ocean, there’s no better place to brunch than the Biltmore’s seaside patio. The hotel is fabulous in a castles-in-Spain way, a 1920’s fantasia of towers and arches and exotic gardens by the sea. Though its recent renovation wasn’t totally successful—the main dining room is stuffy, and the guest rooms are furnished in hotel-issue French provincial—it nonetheless feels as grand as a Cecil B. DeMille stage set. And the patio, looking out over velvety green lawns to the Pacific and the rugged Channel Islands, offers the best oceanfront dining in Santa Barbara.

That afternoon I head for the Easton Gallery, which shows landscapes by local painters who’ve formed an eco-alliance known as the Oak Group. The idea of the Oak Group—contemporary artists who not only perpetuate the 19th-century plein air tradition but pledge half their sales to protect the land they paint—is Santa Barbara to the core: radical, romantic, conservative in the deepest sense. Here is Santa Barbara in its pristine state—la tierra adorada, “the adored land,” rendered lovingly in paint.

January 1, 1998

January 1, 1998