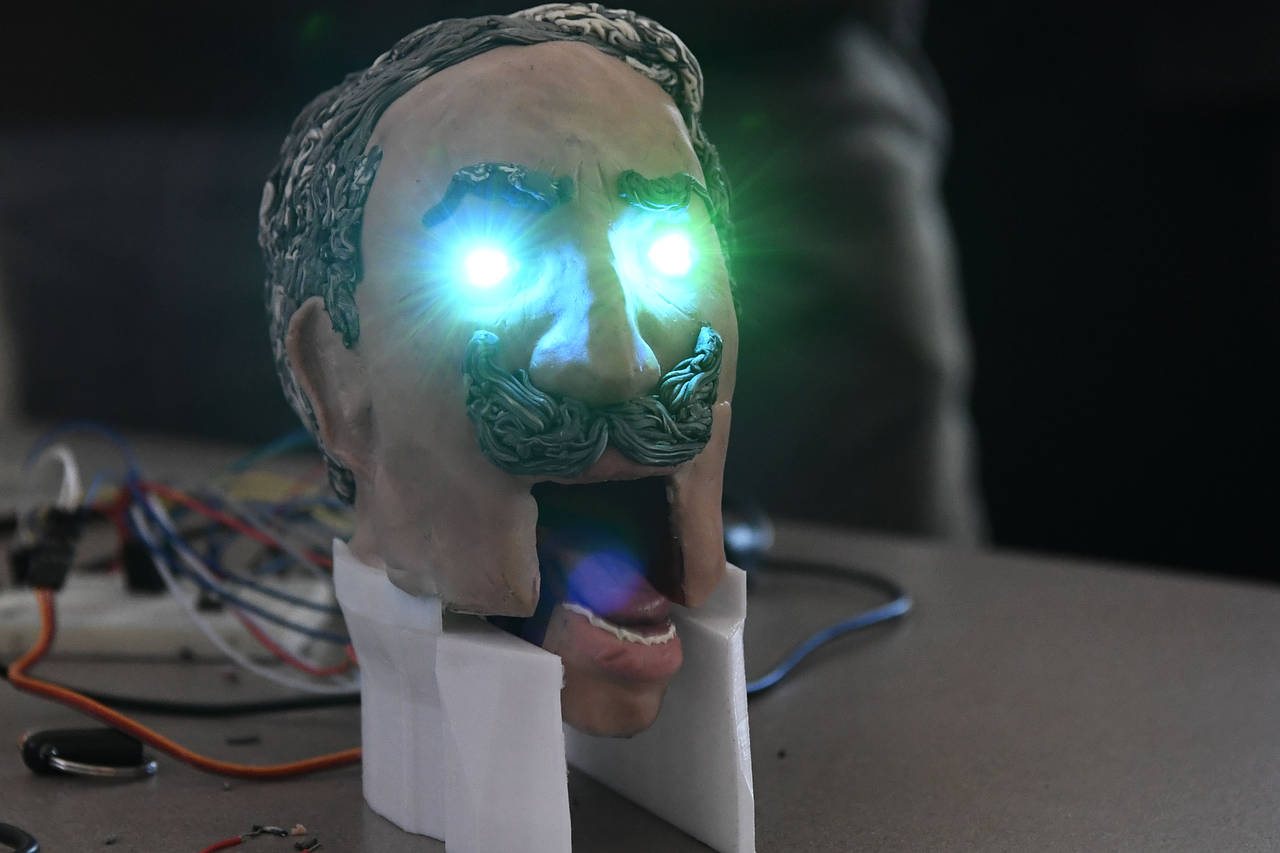

Photo: Getty Images

COSMOLOGISTS TAKE ON the big questions, and in Life 3.0 Max Tegmark addresses what may be the biggest of them all: What happens when humans are no longer the smartest species on the planet—when intelligence is available to programmable objects that have no experience of mortal existence in a physical body? Science fiction poses such questions frequently, but Mr. Tegmark, a physicist at MIT, asks us to put our Terminator fantasies aside and ponder other, presumably more realistic, scenarios. Among them is the possibility that a computer program will become not just intelligent but wildly so—and that we humans will find ourselves unable to do anything about it.

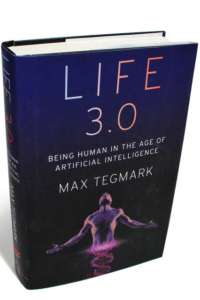

LIFE 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, by Max Tegmark

Knopf, 384 pages, $28

Mr. Tegmark’s previous book, Our Mathematical Universe (2014), put a hugely debatable spin on the already counterintuitive notion that there exists not one universe but a multitude. Not all mathematicians were impressed. Life 3.0 will be no less controversial among computer scientists. Lucid and engaging, it has much to offer the general reader. Mr. Tegmark’s explanation of how electronic circuitry—or a human brain—could produce something so evanescent and immaterial as thought is both elegant and enlightening. But the idea that a machine-based superintelligence could somehow run amok is fiercely resisted by many computer scientists, to the point that people associated with it have been attacked as Luddites.

Books: Digital Life |

Against the StreamMood Machine, by Liz PellyThe Wall Street Journal | Jan. 26, 2025 |

Learning to Live With AICo-intelligence, by Ethan MollickThe Wall Street Journal | April 3, 2024 |

Swept Away by the StreamBinge Times, by Dade Hayes and Dawn ChmielewskiThe Wall Street Journal | April 22, 2022 |

After the DisruptionSystem Error, by Rob Reich, Mehran Sahami and Jeremy WeinsteinThe Wall Street Journal | Sept. 23, 2021 |

The New Big BrotherThe Age of Surveillance Capitalism, by Shoshana ZuboffThe Wall Street Journal | Jan. 14, 2019 |

The Promise of Virtual RealityDawn of the New Everything, by Jaron Lanier, and Experience on Demand, by Jeremy BailensonThe Wall Street Journal | Feb. 6, 2018 |

When Machines Run AmokLife 3.0, by Max TegmarkThe Wall Street Journal | Aug. 29, 2017 |

The World’s Hottest GadgetThe One Device, by Brian MerchantThe Wall Street Journal | June 30, 2017 |

We’re All Cord Cutters NowStreaming, Sharing, Stealing, by Michael D. Smith and Rahul TelangThe Wall Street Journal | Sept. 7, 2016 |

Augmented Urban RealityThe City of Tomorrow, by Carlo Ratti and Matthew ClaudelThe New Yorker | July 29, 2016 |

Word Travels FastWriting on the Wall, by Tom StandageThe New York Times Book Review | Nov. 3, 2013 |

August 29, 2017

August 29, 2017