Bjarke Ingels’s spiralling museum for Swiss watchmaker Audemars Piguet.

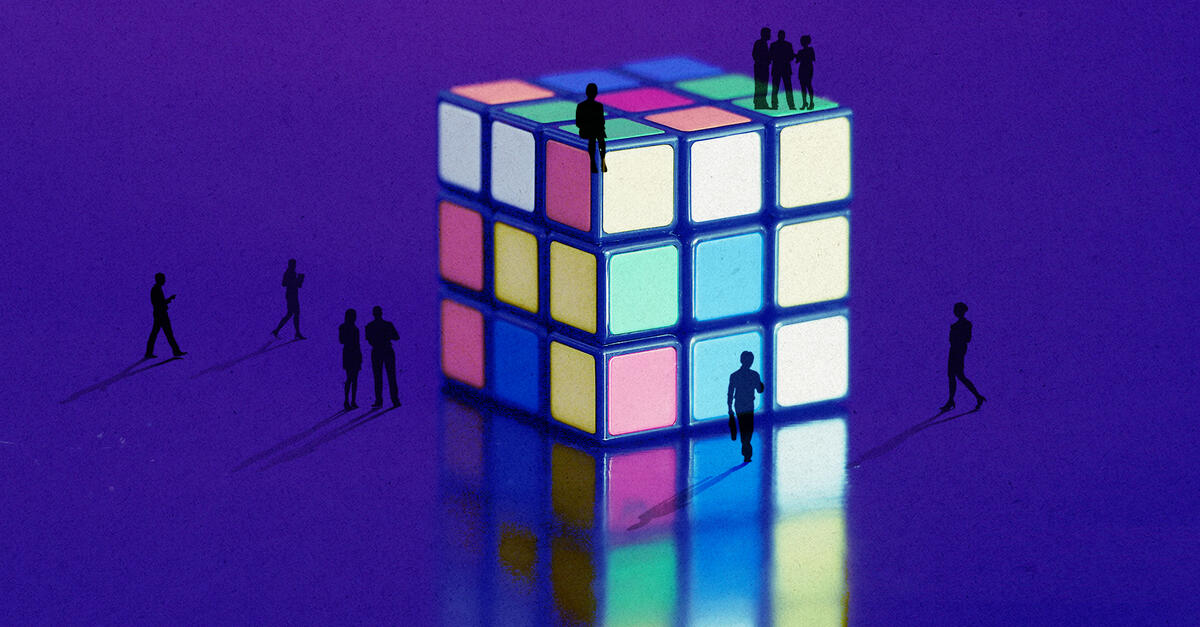

NEARLY SIX DECADES HAVE PASSED since C.P. Snow gave his lecture at Cambridge titled “The Two Cultures,” and in the intervening years the rift he decried has become a chasm. On one side, the STEM disciplines (science, technology, engineering, mathematics); on the other, the humanities. And while English literary types in the 1950s looked down their noses at those in science, the situation in the U.S. today is entirely reversed. Should the humanities even exist? Maybe in a dusty warehouse on the edge of town, but hardly on college campuses, where they suck up resources better devoted to fields of study that might actually lead to a job. Or so you would conclude after listening to the likes of Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen and Florida Gov. Rick Scott. “Is it a vital interest of the state to have more anthropologists?” Mr. Scott asked in announcing new funding priorities a few years ago. “I don’t think so.”

Books: Digital Life |

Swept Away by the StreamBinge Times, by Dade Hayes and Dawn Chmielewski“Is the Albanian army going to take over the world?” Old-media conglomerates famously dismissed Netflix when it was a fledgling startup. Time Warner, Blockbuster: Where are they now?

|

After the DisruptionSystem Error, by Rob Reich, Mehran Sahami and Jeremy WeinsteinThe digital transition was always going to be a messy one—look at the antitrust fights that followed the telephone during the analog era.

|

The New Big BrotherThe Age of Surveillance Capitalism, by Shoshana ZuboffTech companies have shown themselves to be increasingly cavalier with our personal data. Are we handing over too much information?

|

The Promise of Virtual RealityDawn of the New Everything, by Jaron Lanier

|

When Machines Run AmokLife 3.0, by Max TegmarkThe author was taken aback when he observed an AI program teach itself to play an arcade game—and play it much better than its human designers.

|

The World’s Hottest GadgetThe One Device, by Brian MerchantApple’s iPhone—a 21st-century American icon—could not exist without the labors of Bolivian miners and Chinese factory workers.

|

Soft Skills and Hard ProblemsThe Fuzzy and the Techie, by Scott Hartley

|

Confronting the End of PrivacyData for the People, by Andreas Weigend

|

We’re All Cord Cutters NowStreaming, Sharing, Stealing, by Michael D. Smith and Rahul TelangWhat happens when media executives refuse to believe the Internet is a challenge to their businesses?

|

Augmented Urban RealityThe City of Tomorrow, by Carlo Ratti and Matthew ClaudelCan smartphone connectivity and shared data solve the problems of crowded cities?

|

Word Travels FastWriting on the Wall, by Tom StandageTwitter and Facebook are just the latest incarnations of a tradition that dates back 2,000 years, Tom Standage says.

|

May 27, 2017

May 27, 2017