EMILY SPIEGEL IS SERIOUS ABOUT ART. Over the past six years she and her husband, Jerry, a Long Island real-estate developer, have filled their spacious suburban home with nearly a hundred paintings. There’s art in the glass-walled living room, art in the dining room, in the kitchen, in the bedrooms, in the bathrooms, stacked up in the basement. Every serious collection needs a focus, and the focus of the Spiegels’ is on the Neo-Expressionist style that came into vogue at the end of the Seventies—the huge canvases, crammed with heroic imagery, that typify the current generation of European and American painters. At its core is the work of one man: Julian Schnabel, the 34-year-old New Yorker whose name has come to symbolize the movement.

It’s been nearly a decade now since Schnabel and his peers—David Salle, Eric Fischl, Francesco Clemente, Anselm Kiefer—came to the fore. Schnabel was the point man for the whole phenomenon, the one partisans proclaimed a genius and critics derided as a sham. His last show was dismissed by New York magazine as “trash-bin archaeology” even as it was praised in The New York Times for combining the “gestural sweep” of Pollock with the “brash inventiveness” of Picasso. His next show, which opens October 31 at the Pace Gallery on East 57th Street, will likely be even more hotly debated, for the Neo-Expressionists have already experienced their first flush of success and must now fight for their position in art history. His “plate paintings”—oils done on a surface of broken crockery—have already done for painting what Animal House did for fraternity life: They have revived a near-moribund form of expression. What remains to be decided is whether Schnabel himself is a parody or the real thing.

It’s been nearly a decade now since Schnabel and his peers—David Salle, Eric Fischl, Francesco Clemente, Anselm Kiefer—came to the fore. Schnabel was the point man for the whole phenomenon, the one partisans proclaimed a genius and critics derided as a sham. His last show was dismissed by New York magazine as “trash-bin archaeology” even as it was praised in The New York Times for combining the “gestural sweep” of Pollock with the “brash inventiveness” of Picasso. His next show, which opens October 31 at the Pace Gallery on East 57th Street, will likely be even more hotly debated, for the Neo-Expressionists have already experienced their first flush of success and must now fight for their position in art history. His “plate paintings”—oils done on a surface of broken crockery—have already done for painting what Animal House did for fraternity life: They have revived a near-moribund form of expression. What remains to be decided is whether Schnabel himself is a parody or the real thing.

Art Starsand the machinery behind them. |

WangShuiObsessed with the origins of consciousness and humanity’s preoccupation with violence, WangShui hopes that, through AI, love will find a way.

|

A ‘Holopoem’ for the CosmosEduardo Kac found an unusual public space for his artwork — orbiting the sun.

|

Making Art Out of Bombshells and Memories in VietnamTuan Andrew Nguyen’s videos and sculptures uncover haunting artifacts and stories from the Vietnam War.

|

David Byrne Is Totally ConnectedThere’s a new gallery show of his whimsical drawings — and coming this summer, an immersive art-and-science experience.

|

A.I. Meets Fatherhood in an Artist’s New WorkIan Cheng’s latest: a narrative animation powered by a game engine and partly inspired by his two-year-old.

|

Frank Gehry’s Disney Hall Is TechnodreamingData artist Refik Anadol creates a swirling projection on steel for the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

|

Alan Vega Ignored the Art World. It Won’t Return the Favor.A year after his death, the lead singer of Suicide looms over the downtown art scene.

|

The Whitney After AllThe Whitney Museum never really fit in uptown, so it’s relocated to a part of the Village that until recently was a reeking abattoir. Home, sweet home.

|

A Palace of WondersThe Panza Collection mounts a show challenging perceptions.

|

Last LaughJay Gorney sells art that sends up collectors. “They hear tom-toms in the distance,” says a curator, “and they get out their checkbooks.”

|

Cool John B.John Baldessari got rid of all the extraneous stuff, like form and beauty. Now he’s the éminence grise of conceptualism, in the spotlight at last.

|

As the Art World TurnsThe mix of art, big bucks and hype has turned the art world into a frothy soap opera. Which brings us to Julian Schnabel . . .

|

The Spiegels are convinced he’s real. They own four of his paintings, one of which—an early work called The Dancers (for Pasolini)—hangs in an alcove off the living room. The image in The Dancers is of a dark, vaguely cone-shaped object, like a spinning top, upright against a red background, with a black companion tilting off to one side. The surface of the painting is broken by five protruding horizontal lines, each about a foot apart, that resemble the slats of venetian blinds. “It’s beautiful,” declared Robert Pincus-Witten, the Spiegels’ art adviser, a painfully erudite man in a leather blazer. “The colors, the shapes. the virtual impossibility of that image—it’s like a shadow cast into space.”

It was at the Mary Boone Gallery’s first exhibition of his plate paintings that Emily Spiegel became acquainted with Schnabel’s work. She was immediately bowled over. She and her husband had been looking at art for years, but they’d bought only what they liked and their collection was scattershot—a Henry Moore here, a Post-Impressionist there—”not a wholly embarrassing situation,” as Pincus-Witten put it, but hardly enough to make them a force in the international market. And while Schnabel himself was virtually unknown, Mary Boone was an extremely savvy dealer with big plans in mind. As a result, all the Spiegels could do was look. “I just knew it was important,” Emily recalled as she sat in her living room, a just-purchased 1962 Warhol leaning against the wall beside her. “It was almost visceral. But I wasn’t able to get it because I wasn’t an important enough collector at that point. I had a lot of work to do.”

What she did was sell most of her collection and call up Pincus-Witten, a well-connected critic and art-history professor at Queens College, and ask him to advise her. Together they came up with a strategy for building a first-rate collection. The obvious place to start was with Schnabel and his friend David Salle—the Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg of Neo-Expressionism, according to the buzz in the galleries. “Important stylistic shifts generally concentrate on a small number of people,” Pincus-Witten explained. “It was very clear that this one had focused on David and Julian, so the issue then became getting to David and Julian. Now, I had already written about them, and I had some access to them and to Mary, so that was that.”

Besides Schnabel and Salle, the Spiegels’ new collection includes almost every hot name in New York. There isn’t anyone who wouldn’t be thrilled to sell them a painting today, especially since they gave a Schnabcl to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “I think Julian is one of the most important and powerful artists who are around today,” Emily Spiegel declared. “He’s disturbing. It’s not just surface art, it’s deep and it’s meaningful, it’s brooding, it’s heroic. And he’s also intelligent, very opinionated, dynamic, a loving husband and father—I completely believe in him, and I’m certain many other collectors do too.”

THIS THEY DO, so many of them that today, seven years after his first New York gallery show, Schnabel’s name is virtually synonymous with contemporary painting. To understand the Schnabel phenomenon—what this person has to say and how he’s come to dominate contemporary art, achieving in a couple of years a commercial success that has eluded other painters all their lives—it’s necessary to step back to the early Seventies, when he came to New York from Texas to study at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The art world then was in a state of torpor. The dynamism of the Sixties had led to a series of increasingly “difficult” exercises—earth art, performance art, conceptual art. process art. Artists stopped thinking of art as a product and started thinking of it as an idea. Meanwhile, major museums were drawing crowds with blockbuster exhibitions of twentieth-century paintings, SoHo was becoming a mecca for sophisticated young people in search of an avant-garde, and frustrated collectors were casting about in vain for something to collect. It was a situation that couldn’t last.

An early wax painting: “The Dancers (for Pasolini), 1977-78. 74 x 86 ½ x 3 inches.

Schnabel spent a year at the Whitney, then traveled extensively in Europe, where he took in not just the masters but also such forward-looking contemporaries as Joseph Beuys and Jannis Kounellis. While in New York he painted by day and worked by night, supporting himself as a chef at the Lower Manhattan Ocean Club, a downtown nightclub whose owner, Mickey Ruskin, had introduced the art world to the rock world in the Sixties with Max’s Kansas City. The scene at Max’s was over by this time, but the Ocean Club drew a comparable crowd—and for the new generation just getting out of art school, New York’s punk-rock scene, raw and alive, offered a bracing antidote to the dry reductionism of SoHo. At the Ocean Club, they could watch Talking Heads—a fledgling band formed by ex–art students from the Rhode Island School of Design—sing “I’m painting again,” even though painting seemed almost dead.

At the Locale, Ruskin’s next place, Schnabel shared the kitchen with David Salle, another struggling young painter, who had come to work as his sous-chef. It was at the Locale that he met Mary Boone, a young RISD graduate—she had studied there at the same time as Talking Heads—who’d been working at Bykert, a minimalist gallery on Madison Avenue, and was planning a gallery of her own. He was one of hundreds of young painters whose work she went to see; it struck her as unfashionable but provocative—physical, even carnal, and redolent of death. The fashion, however, was changing, and Schnabel was in step with the shift.

The reaction that had been building against conceptualism finally broke through in 1978 with two important shows—the “New Image Painting” show at the Whitney and the “‘Bad’ Painting” show at the New Museum of Contemporary Art. That was the same year Mary Boone opened her gallery at 420 West Broadway. It was a tiny space she had had to wheedle away from the art-moving firm that owned it, but the building was the most prestigious in SoHo, the home of four of the most influential dealers in contemporary art. In February 1979, Boone gave Schnabel his first one-man show in New York. Few critics even noticed him, but Boone wasn’t waiting for their approval. Leading collectors of contemporary art—those with the big reputations and the good museum ties—had already been led to his studio and given the pick of his work. Less important collectors never got the opportunity to buy: The four paintings in the show were all sold before it opened.

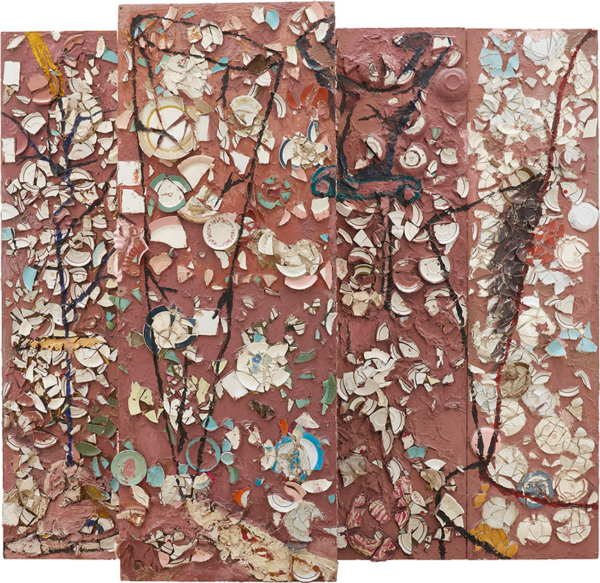

Schnabel’s first plate painting: “The Patients and the Doctors,” 1978. 96 x 108 x 12 inches.

That fall, Schnabel got a second show, and in this one, for the first time, Boone displayed his plate paintings. Inspired by Antoni Gaudi’s mosaic-tile benches in Barcelona, he’d glued broken cups and saucers to a wooden backing and slathered them with paint, producing crude but powerful images that staggered under the weight of art-historical references. Many critics were stunned; some lost all control. “Maybe these paintings shouldn’t be kept in the home at all,” wrote Rene Ricard, a poet and a friend of Schnabel’s, “but, rather, chained in the basement like a pet gorilla.” Leo Castelli, the man who’d made Pop Art—who’d brought us Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist—came in and was awestruck. Barbara Jakobson, a collector and trustee of the Museum of Modern Art, introduced Castelli to Schnabel, and soon a new deal was struck: Schnabel would be represented by both dealers, Boone and Castelli, their share to be split fifty-fifty.

Castelli wasn’t the only important figure to be wowed by Schnabel. Henry Geldzahler, a longtime tastemaker in the art world, went to his studio and was so impressed he fell down the stairs on his way out. Andy Warhol started taking him out to dinner and introducing him to his friends. Schnabel’s ego, never petite, expanded dangerously under the pressure. When he and David Salle—who by this time had become the other hot number at Boone—decided to trade paintings, he took Salle’s offering and drew Salle’s face across one side of it in orange paint. On another occasion, discussing a Jasper Johns opening with some fellow artists at Odeon, the fashionable lower Manhattan restaurant, he announced that he liked his own work better: “Mud in Mudanza would have wiped that out.”

Inevitably, there were mumblings—snide asides at Boone’s clever machinations, at his own unflagging capacity for self-promotion. Some important collectors refused to touch him; several museums did likewise. Art magazines showed more interest in his publicity than in his paintings; Time critic Robert Hughes denounced his work as “callow” and “pretentious” and derided his broken plates as “the severed ear of the ’80s.”

None of this harmed Schnabel in the least. It may have been true. as Hughes alleged, that his paintings were a pastiche, full of frankly acknowledged steals from other artists, but the upshot of it was that people saw them as a synthesis of a lot of ideas that were in the air. Collectors admired him because he was wild and untamed, because he offered them such a visceral experience. Critics and curators were impressed not merely by the thematic content of his work but by the imaginativeness of his technique. To them, the broken plates were not a gimmick but a radical gesture that destroys and confuses the image, just as the paintings on velvet that followed were a calculated affront to taste. And yet applying such novel techniques to something as traditional as figurative painting was an act many older artists considered retrograde. It made Schnabel seem radical and reactionary at the same time—which, of course, was the point, for this new avant-garde looked back: In the same way that New Wave musicians set about reinventing rock and roll, Schnabel and his peers were trying to reinvent painting.

What seemed to upset Schnabel’s critics most was that as a painter he became a bigger star than most musicians. “I think some of the paintings Schnabel has made are very ambitious and striking,” said Marcia Tucker, director of the New Museum, “but this instant-fame business is very distressing to me. If you want to be a rock star, you should be one. The goal of an artist is to explore the regions of the human heart, and when that becomes deflected by sales and brouhaha, something is wrong. The most interesting artists are the ones who learn from their failures and not from their successes—and this is not what has happened here.”

An early record for Schnabel at auction: “Notre Dame,” 1978, 90 x 108 x 12 inches, sold for $93,500 at Sotheby’s in 1983.

THE “INSTANT-FAME BUSINESS” has become a critical issue for Schnabel and his generation. One reason young artists turned to punk rock in the Seventies was for the instant gratification it seemed to offer—no need to struggle for years in a lonely loft, just pick up a guitar and play. The rock scene burned out quickly, but those who went back to painting—or never left it—discovered that art could now offer fame and money as quickly as pop music or the movies. One of the first people to make this discovery was Schnabel.

One model for this new generation was Jackson Pollock, the pioneer Abstract Expressionist. The idea of the heroic painter—brilliant, angst-ridden, larger than life—had reached its zenith with the Abstract Expressionists, only to be punctured by the Pop artists, nullified by the Minimalists and extinguished by the conceptualists. After the Seventies, the idea was one many people, artists and collectors alike, were aching to believe in. Schnabel was an artist who could reconstitute the myth, who could restore people’s faith, who could make them feel good again. You could almost imagine him invading Grenada.

A lot had changed since Pollock’s day, however. No longer was it cool to come to your patron’s party drunk and piss in the fireplace, as Pollock had done at Peggy Guggenheim’s so many years before. On the other hand, Pollock never sold a painting in his life for more than $9,000; Schnabel’s prices reached four times that amount before he was 30, and now they’re in the $60,000 range. Since he does nearly thirty paintings a year and splits the money fifty-fifty with his dealer, that would give him a gross income approaching $750,000 per year. He’s used the money to create a lifestyle that rivals his collectors’, buying a Cadillac and a Mercedes and a Bentley, eating at the most fashionable restaurants and turning both his loft in the city and his country house in the Hamptons into showcases of his wealth and taste. A few years ago, for example, he ordered thirty yards of hand-painted gold cloth at $220 per yard to be made into curtains.

“This idea of heroic art really cracks me up,” Schnabel said. “I’ve been reading hero this, hero that for the past five years. I don’t know what that means, heroic.”

Mary Boone’s business acumen served both of them well. Hers was a new tactic in the art world, one that presumes a speculative approach to collecting. “Leo Castelli never sold art as an investment,” said an accountant who’s knowledgeable about the field. “But when a certain diminutive young lady came onto the scene, her whole thing was, ‘They’re $10,000 now, $15,000 next month, $20,000 the month after that and $30,000 in a year.’ I think you have to give that young lady a great deal of credit—for lack of a better word. And when you see big-shot Wall Street investors like the chairman of PaineWebber coming to SoHo, I think that says something about the possible appreciation of art vis-à-vis Xerox or IBM.”

Certainly Boone’s technique wouldn’t have worked if prices for early schools of contemporary art hadn’t already been skyrocketing. Sotheby’s celebrated 1973 auction of the Robert and Ethel Scull collection is usually cited as the watershed: Fifty works went for a total of $2.24 million, smashing records for artists such as Johns, Rauschenberg and Rosenquist. Since then, representative works by celebrated living artists have appreciated rapidly in value. At the Scull sale, for example, a large, abstract canvas by Willem de Kooning went for $80,000: in 1984, a much smaller oil-on-paper was sold on the block at Christie’s for just under $2 million. Boone’s genius lay in her ability to manipulate the speculative fever such sales have engendered.

Boone arrived at the perfect time to sell the new generation of painters to a new wave of collectors who were attracted to art as an investment opportunity. With Schnabel, too, timing was all. “I think Julian’s success was the same as any artist’s success,” she said. “He came into the public eye at a time when there were a lot of very good artists around, so the public became extremely interested. Plus, he did certain things first. That was basically it. Every artist wants to think they’re famous only because of their work”—she permitted herself a slight smile as she sat behind the bronze-inlaid antique desk in her icy-white office—“but that’s a very naive concept.”

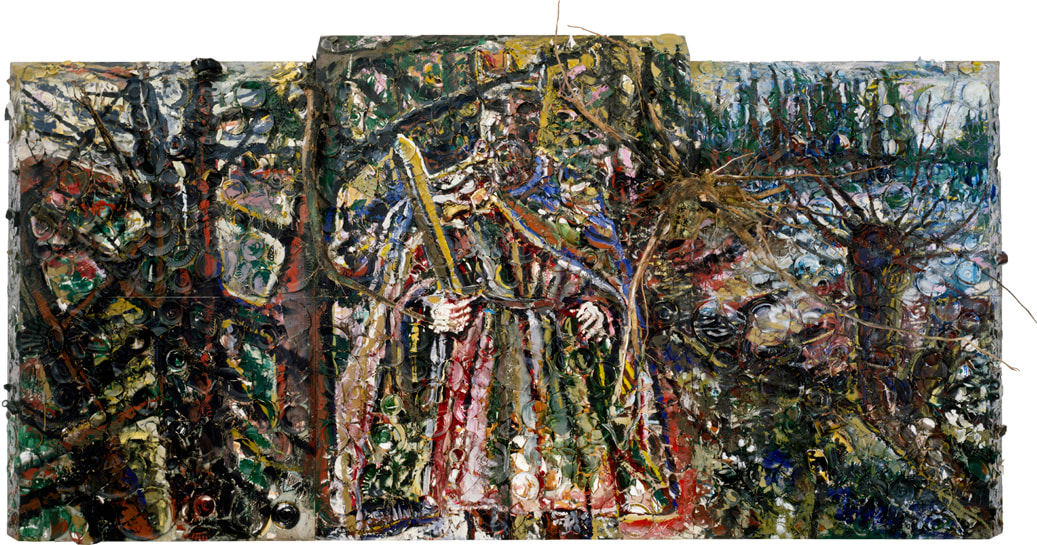

“The Mud in Mudanza,” 1982, 115 x 228 inches. “The broken saucer would be the severed ear of the ’80s, spelling emotional hunger, pent-up violence, expressionist authenticity,” Robert Hughes wrote in Time.

THESE DAYS, MARY BOONE works out of 417 West Broadway, a dramatically converted garage across the street from her original space at 420. It’s far larger than the old place, but only about half of it is devoted to public exhibition space. The other half, reached through a doorway that’s blocked to the public by a velvet rope, is a stunning suite of offices and reception areas where employees and collectors confer in hushed tones in German, English and Italian. People come here from all over the world to buy Salle, to buy Fischl, to buy Germans like Georg Baselitz and A. R. Penck and Kiefer. But they no longer come to buy Schnabel, because two years ago Schnabel abandoned Boone and Castelli for Arne Glimcher and his Pace Gallery uptown. There his work appears in the company not of other Neo-Expressionists but of some of the greatest artists of the twentieth century—Mark Rothko, Jean Dubuffet, Pablo Picasso.

“I thought it was a bad idea,” said Boone, ruby-lipped and raven-haired, “and I told him so. I think Arnold Glimcher is a great dealer of a certain kind—but in terms of a living artist who’s been making art for less than twenty-five years, I think it’s important to be in a situation that’s vital, not a situation that’s about merchandising. Julian understood that. And I understood his complaints because he’d voiced them before. He doesn’t like Eric Fischl’s work, he didn’t like the entry of a lot of the German artists.”

If he didn’t like them, what did he want Boone to do?

“Only represent him! I mean, I’ve never even gone into that because I’m not interested in it. I think it’s a childish way of looking at things, and just because a person acts childishly you don’t have to indulge them.”

Schnabel’s move, like everything else he does, generated an enormous amount of talk. Leo Castelli denounced him publicly for wanting to be the “King Kong” of the art world. Insiders said he made the switch because Glimcher offered him a guaranteed annual income of $1 million—a rumor both Glimcher and Schnabel denied. But whatever his arrangement with Pace, there seemed little doubt that he’d make money there. Glimcher is a canny salesman with a highly profitable sideline in limited-edition prints and a business strategy that runs directly counter to Boone’s. “When Pace netted this stuffed goose,” said one disaffected dealer, “the joke was that now there’ll be enough plate paintings for everyone.”

“He came into the public eye at a time when there were a lot of very good artists around,” said Mary Boone, “plus he did certain things first. That was basically it.”

What no one can deny is that by joining Pace’s roster Schnabel put himself in a more rarefied context—not a bad idea now that the excitement is focused on younger painters from the East Village. Neo-Expressionism is about to enter a long and painful period of adjustment, at the end of which maybe three or four names out of the dozens now bandied about will emerge as significant. Funny things can happen to an artist after the newsprint yellows and fades: Museums can consign paintings to the basement, big names can be forgotten. Schnabel’s challenge now is to demonstrate endurance. This explains two of his current projects: a lavishly illustrated autobiography, tentatively entitled A Bouquet of Mistakes, to be published by Random House, and a twelve-year retrospective of his work that will be on view in Europe throughout the fall and winter. The retrospective—his first—includes some thirty-four works, among them The Patients and the Doctors, his first plate painting, and The Mud in Mudanza, which normally graces his living room.

Financially, however, an artist’s report card is what happens on the auction block, and there Schnabel has encountered some disquieting news. Three years ago, an early plate painting called Notre Dame fetched the astonishing price of $93,500 when it was put up for sale at Sotheby’s. (The buyer was a Washington art consultant who told The Washington Post she went after it because Mary Boone wouldn’t sell her one.) But on the eve of his first show at Pace, two more of his paintings were put up at auction and neither met the secret reserve price required for a sale. These weren’t major works, and since the competition at auctions is usually for the best works of a major artist, the incident may not mean much. Certainly everything about that first Pace show—the dramatic installation, the lavish catalogue, the glowing text by art historian Gert Schiff—seemed to declare it meant nothing at all.

Like earlier Schnabel shows, this one assaulted the viewer with an overwhelming physicality. The pièce de résistance was a monumental plate painting, nearly ten feet by twenty, entitled King of the Wood. Inspired by a myth described in Frazer’s The Golden Bough, the painting depicts a grim figure in a moonlit forest, sword at the ready, alert for the man who will slay him and succeed him, just as he himself slayed the man whose position he now holds. It could well have been a self-portrait.

“King of the Wood,” 1984, 114 x 234 inches. “Schnabel at his best,” wrote Michael Brenson in The New York Times, a triptych with spruce roots that “sweep us into a pictorial world of Baroque violence and decay.”

SCHNABEL’S NEXT SHOW may contain some surprises. Last year, in London, he showed a number of paintings done on antique linoleum—horrific images in which unidentifiable organs are displayed like ignominious splats. Since then he has departed from the rampant physicality of these and his earlier plate paintings for a style that is by comparison peaceful, restrained, almost cerebral. His newest paintings, done this spring and summer in oil and tempera on muslin, offer strange and vibrant landscapes in which fantastic beings cavort among jeweled trees. One work shows his daughter Stella being anointed by a many-breasted plant. The three paintings of the Rebirth series are dominated by a field of pink-and-white cherry blossoms. All that remains from his earlier work is the overwhelming scale: None of these new paintings is less than seven feet high.

Like his work, Schnabel himself is theatrical, larger than life. When I met him at his loft, he looked tanned and fit, his brown hair streaked with gold. An assistant sat at a distant desk fielding phone calls; five mammoth paintings—a Kiefer, three Schnabels and a portrait of Schnabel by Warhol—guarded the walls; and a few feet away. beyond the railing, the office opened up to reveal his studio, which lay like a yawning chasm on the floor below.

Julian, sockless in blue slacks and TopSiders, seemed friendly and unguarded. He did not, however, seem too happy about being in New York. “There’s a lot of weird stuff going on,” he said. “This whole thing about success is so retarded. I mean, what’s it going to do, keep you from getting cancer? Is it going to keep your children safe?” He looked exasperated.

“I mean, I don’t see this as a career. You just wake up and try to do something that makes you feel like you’re not too much of a waste. Try to find something small that might be a signal that somebody could recognize. Something like that little William Carlos Williams poem: ‘I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox/and which you were probably saving for breakfast/Forgive me they were delicious so sweet and so cold.’

“I don’t see this as a career. You just wake up and try to do something that makes you feel like you’re not too much of a waste.”

October 1, 1986

October 1, 1986