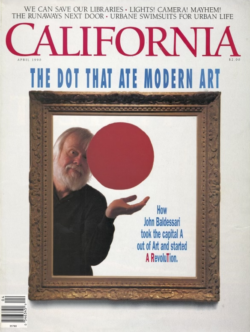

This profile appeared on the eve of John Baldessari’s first major retrospective in California, a “city” magazine for the entire state that was published from 1976 to 1991. The exhibition, organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, signaled the emergence of LA as a major art center, not the provincial backwater it had long been considered. This article is based on multiple interviews in New York and LA with Baldessari himself and with MOCA’s then-director, gallerists, and former students and colleagues at CalArts, the art school Baldessari helped put on the map. Baldessari died in 2020 at age 88.

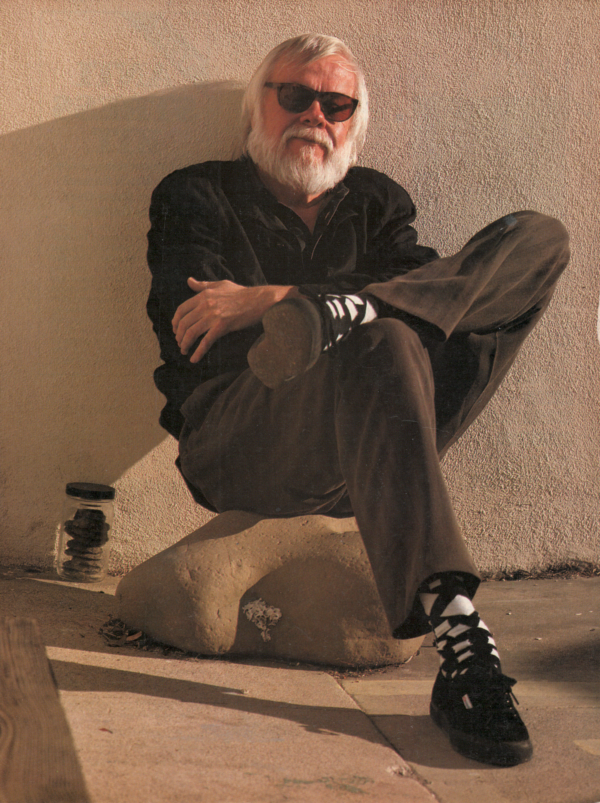

Photo by Doris Jew.

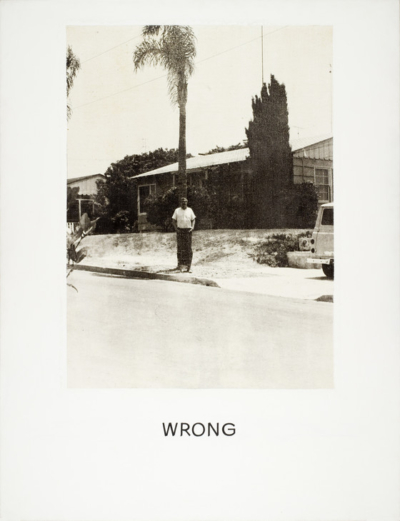

JOHN BALDESSARI HAS THIS thing about rules. In 1967 — not a good year for rules generally — he made a photograph of himself standing directly in front of a palm tree and labeled it Wrong. That was his way of dealing with the rule that amateur photographers should ask their friends to stand to one side of tree trunks and other tall, spindly objects that might otherwise appear to be growing out of their heads. Around the same time, wrestling with the rule that paintings ought to have some sort of pictorial content, he commissioned a sign painter to letter the words PURE BEAUTY across a canvas. Baldessari was too busy teaching art to paint anything beautiful himself, and nobody seemed to want the paintings he made anyway. This way he could just communicate the idea and move on.

Or so he thought. Two years later, he grew so frustrated with the rules that governed the contemporary art world that he chopped up all of his paintings, carted them off to a San Diego crematorium and had them reduced to ashes. He took them home in ten boxes — nine adult- and one baby-sized. He did this out of desperation. He’d been working in an abandoned theater his father owned in National City, the gritty industrial suburb of San Diego where he’d grown up, and the theater was filling up with paintings done in imitation of Cézanne and Matisse — his paintings, unsold and unwanted.

“It hit me that I could be suffocated with paintings in there,” he says. “I decided I had to do something dramatic.”

“It hit me that I could be suffocated with paintings in there,” he says. “I decided I had to do something dramatic.”

Baldessari wasn’t the only one feeling suffocated. Painting was the prescribed mode of expression at the time, and not just any painting. To be taken seriously, you had to make abstract, minimalist paintings — canvases that were impersonal, austere and more or less blank, like Frank Stella’s early work. But what if you wanted to make art that wasn’t abstract, or minimalist, or even painting? What if, like Joseph Kosuth, you wanted to make art out of words and photographs? What if, like Vito Acconci, you wanted to make art that couldn’t even be hung on the wall — art that was just something you did, like throwing a rubber ball down the street?

With minimalism, art history seemed to end with a blank wall—a wall conceptualists like Baldessari were determined to break through.

Art Starsand the machinery behind them. |

WangShuiObsessed with the origins of consciousness and humanity’s preoccupation with violence, WangShui hopes that, through AI, love will find a way.

|

A ‘Holopoem’ for the CosmosEduardo Kac found an unusual public space for his artwork — orbiting the sun.

|

Making Art Out of Bombshells and Memories in VietnamTuan Andrew Nguyen’s videos and sculptures uncover haunting artifacts and stories from the Vietnam War.

|

David Byrne Is Totally ConnectedThere’s a new gallery show of his whimsical drawings — and coming this summer, an immersive art-and-science experience.

|

A.I. Meets Fatherhood in an Artist’s New WorkIan Cheng’s latest: a narrative animation powered by a game engine and partly inspired by his two-year-old.

|

Frank Gehry’s Disney Hall Is TechnodreamingData artist Refik Anadol creates a swirling projection on steel for the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

|

Alan Vega Ignored the Art World. It Won’t Return the Favor.A year after his death, the lead singer of Suicide looms over the downtown art scene.

|

The Whitney After AllThe Whitney Museum never really fit in uptown, so it’s relocated to a part of the Village that until recently was a reeking abattoir. Home, sweet home.

|

A Palace of WondersThe Panza Collection mounts a show challenging perceptions.

|

Last LaughJay Gorney sells art that sends up collectors. “They hear tom-toms in the distance,” says a curator, “and they get out their checkbooks.”

|

Cool John B.John Baldessari got rid of all the extraneous stuff, like form and beauty. Now he’s the éminence grise of conceptualism, in the spotlight at last.

|

As the Art World TurnsThe mix of art, big bucks and hype has turned the art world into a frothy soap opera. Which brings us to Julian Schnabel . . .

|

For the next decade and a half, from 1970 until 1985, Baldessari was the éminence grise of the California Institute of the Arts, the school Walt Disney founded and gave nearly half his estate to. Under Baldessari’s influence, CalArts became a center of conceptualist thought; within a few years, it supplanted Yale as the leading art school in the country. Baldessari became a guru for young artists who felt free to do many of the same things he had done, and who in many cases became phenomenally successful doing them. David Salle, Sherrie Levine, Barbara Kruger — many of the biggest art stars of the eighties built their names on techniques and ideas they borrowed from Baldessari. Meanwhile, Baldessari himself labored in semi-obscurity: he was highly regarded in Europe, where conceptualism’s intellectual conceits fit neatly with the trendy philosophy of post-structuralism, but he was little known in this country and all but ignored in California.

Then the fame of the students began to reflect on their mentor. There was the day that Baldessari and Salle had simultaneous openings in New York—Baldessari at the Sonnabend Gallery on West Broadway, Salle one flight down at Leo Castelli. Baldessari’s was a pleasant affair: a few dozen people came and drank wine and stood around talking, just as they do at five or six other openings every week of the season. Salle’s was an event: the Castelli gallery was jammed, not just with the art crowd, but with media people and fashion people and scene makers and tastemakers and hangers-on, most of them drawn not by the lure of art or even talent but by the raw need to commune with big bucks and instant celebrity. And then came the moment when the object of this massive transference, Salle himself, went upstairs to congratulate his mentor. The rest of the crowd has been following him up ever since.

And not just in New York. As Los Angeles began to emerge as a major art center, Southern California’s dealers and curators and collectors slowly realized Baldessari’s importance. After ignoring him for years, they enshrined him. Wrong, the photograph that demonstrated how “not” to take a photograph, was acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Now his work has joined the holdings of such prominent Los Angeles collectors as Toyota magnate Frederick Weisman and Dynasty producer Douglas Cramer. Real estate developer Eli Broad has created an entire Baldessari room in his private museum in Santa Monica [precursor to The Broad in downtown LA]. In March, after bidding against the County Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art staged the first full-scale Baldessari retrospective in the United States — a show that will travel to San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art in July, then to the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., and finally to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Says MOCA director Richard Koshalek, “I think John is going to have to fasten his seat belt.”

BALDESSARI’S STUDIO IS ONE of those flotsam-like places that seem inevitably to wash up near the beach in Santa Monica. Tucked in behind a surf shop and a dry cleaner’s, with a rickety screen door opening onto a dusty parking lot, it looks like a New York loft plunked down in a sleepy California town. The floor is gray cement; trestle tables hold stacks of correspondence, boxes, reels of film, old photographs; skylights make do for windows. Although Baldessari has lived here since his divorce a decade ago, he still seems to be camping out. A nondescript sofa and chair inhabit one corner, next to a small kitchen area. The closet is a pole suspended horizontally above the floor. Tacked to the wall opposite the dining table is an enormous black-and-white photograph of a potato, a knife and a pair of hands.

Originally, the photograph was part of an eight-by-ten glossy of a man in a white lab coat—some sort of food technician, apparently—slicing potatoes in an antiseptic kitchen setting. “I’ve always liked images that are instructive in nature,” Baldessari remarks. “I get tired of seeing things that are tasteful. Maybe it’s something perverse in my nature, but I like the idea of art being ordinary. It should just be work you like to do — that’s what makes it art. To go beyond that is a bit pompous.”

John Baldessari, “Pure Beauty,” 1966-68. Glenstone, Potomac, Md.

At six feet five inches, with silver hair and a silver beard, Baldessari is a striking-looking man, almost commanding except for his stooped shoulders, mild manner and slightly absent-minded appearance. His speech, while soft and tentative, has a wry edge. “The paradox,” he goes on, “is that art should he ordinary, but it should also he transforming.”

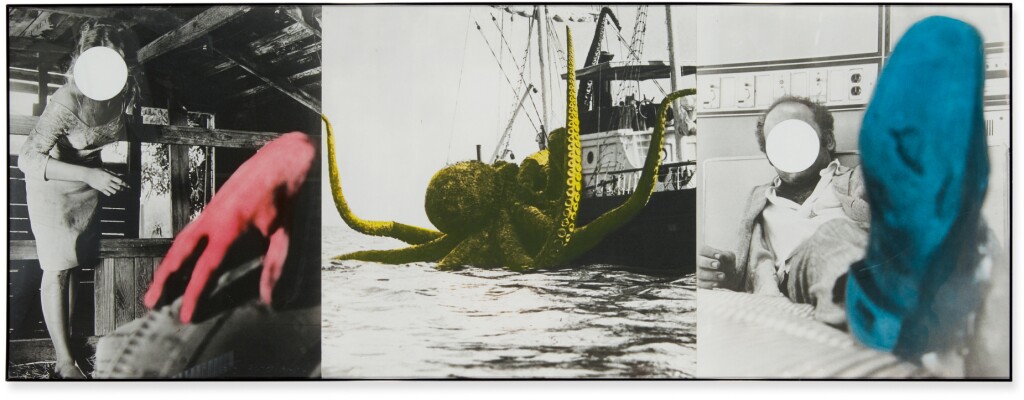

For the last ten years or so, Baldessari has been making collages from ordinary old photographs. He has milk cartons and filing boxes full of them — old magazine photos, stills from long-forgotten movies, random glossies picked up for a dime apiece at bookstores, the more anonymous the better. “I want them to be generic,” he says, gesturing vaguely toward his bookcases. “I’m interested in them as images in the collective unconscious.” Working from this cache, he crops them, blows them up, juxtaposes them with others, adds bits of color here and there, and makes art.

Directly beneath the potato photo is a large color photograph of twelve different fruits, each labeled with a different month. The gleaming fruit, blown up from an advertising brochure for a fruit-of-the-month club, contrasts sharply with the grainy realism of the potato. Before he is finished, Baldessari will color the potato blue and the knife yellow. Blue stands for hope and aspiration, he explains, yellow represents chaos, the random factor. To him, then, the knife signifies fate cutting into a person’s life. Baldessari is thinking of calling it One Potato/Blue Potato—a reference to the children’s rhyme and, by extension, to the monotony of counting and the endless chores of everyday life.

Like much of Baldessari’s art in recent years, this piece packs a hot message in a cool medium — emotionally charged, yet distant and impersonal. And though he’s been working on it for more than a year, it looks simple, like something anybody could have done.

He chuckles. “What people don’t see is all the agonizing that goes into making it look like that. Matisse said, ‘They don’t understand that I put those drawings back on the anvil 20 or 30 times.’ And that’s what art is — you’re trying to bend things to your will.”

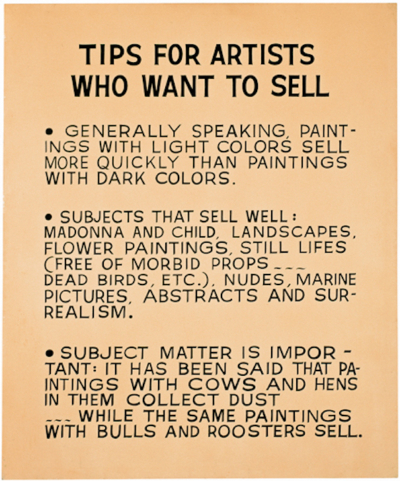

John Baldessari, “Tips for Artists Who Want To Sell,” 1966-68. The Broad, Los Angeles.

ONCE HE’D CREMATED his paintings — an act he conducted with proper ceremony and announced with a legal notice in the newspaper — Baldessari finally felt he was beginning to understand what conceptual art was supposed to be. It had to do with getting rid of all the extraneous stuff, like form and beauty, and reducing art to its absolute essentials. The paintings he’d made were gone, but the idea of the paintings lived on in his head. That’s where the art was, he concluded, not in a lot of messy brushstrokes on canvas.

Symbolic self-immolation would be a radical act for any artist, but it was particularly radical for Baldessari. The son of an Italian-immigrant father and a Danish-immigrant mother, he’d grown up in a Depression-era household where nothing was ever thrown away. His father, starting out as a coal miner, had taken the tobacco out of cigarette butts and rerolled it to sell to other miners. Later, entering the salvage business, he’d torn down houses and used the materials to build new houses. One of Baldessari’s earliest memories was of pulling nails out of old boards so they could be reused. The rabbits he raised provided meat for food and pelts for sale. He knew art was something nobody asked you to make — it wasn’t like plumbing, which was useful — but the realization that nobody wanted his art was almost overwhelmingly demoralizing. Especially since the reason he’d gone into art in the first place was to escape his father’s domination: “Art was the one place he couldn’t get to me.”

And yet, cremating his paintings allowed Baldessari to wring value from them in ways his father would surely have approved of. He didn’t just leave the ashes on a shelf to collect dust. Some of them he baked into cookies, which were exhibited in a conceptual art show at the Museum of Modern Art. Some of them he poured into a bronze urn, which was embedded in a wall of the Jewish Museum in New York, behind a bronze plaque that read, JOHN ANTHONY BALDESSARI, MAY 1953-MARCH 1966. The idea of the conceptual artist rising phoenix-like from the ashes of painting was a powerful one, and it gave him a great deal of currency in the movement.

He was trying to de-glamorize art, “to take out the Art-with-a-capital-A and get down to the issues.” The paradox, he says, “is that art should be ordinary, but it should also be transforming.”

Like his fellow conceptualists, Baldessari is a spiritual descendant of Marcel Duchamp, the Dada artist who signed a urinal and submitted it to a New York art show in 1917. What Duchamp was saying with his “readymades” — that an artist can turn anything into a work of art simply by declaring it one — prefigured the conceptualist argument that what counts is not the execution but the idea — that the object matters less than the thought behind it.

Baldessari wasn’t really a painter, anyway. As an art teacher — first in the San Diego public schools, then at Southwestern College in suburban Chula Vista, finally at UC San Diego — he dealt not with art itself but with textbooks and photographs. He would make texts and photos his art. And why not? Words had made him an artist. Even as a kid, he’d understood that books would be his ticket out of National City, a ticky-tacky little burg near the Tijuana border, where the sawmill and the sewage-treatment plant and the fish-packing plant conspired to foul the air. His father used to ask him why he was always buying hooks in bookstores when he could get them wholesale for a quarter apiece. To his father, a book was a book. John ignored him and read on.

John Baldessari, “Wrong,” 1966-68. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

He studied art history at Berkeley, then got his M.A. from Cal State San Diego in 1957. Painting in his free time and teaching art for a living, he lived with his wife and their two small children in a ranch house his father had built in National City. He didn’t know anybody who showed in galleries or museums, so he relied on books and magazines to decipher the art world. He learned what an artist’s studio was supposed to look like from a monthly feature in ARTnews. In 1968, he had his first solo show in Los Angeles. The response was minimal, except for a review in Artforum that sparked interest in New York.

At the time, Los Angeles was dominated by the Venice crowd—Billy Al Bengston, Larry Bell, a group of artists who’d made a name for themselves in the early sixties with an offshoot of minimalism that was noted for its hard, glossy surfaces and its extreme attention to craftsmanship. Although in New York this “finish fetish” was dismissed as slick and shallow (just like everything else in California, it seemed), Los Angeles collectors viewed it as a perfect evocation of the local light and ambience. Certainly they had little use for the strange “word paintings” and peculiar photographs Baldessari exhibited.

In 1970, however, Baldessari broke out—first with a solo show in New York, then with a teaching job at CalArts, an interdisciplinary arts academy in Valencia that opened that fall near the Disney movie ranch. He moved to Santa Monica, a 28-mile commute through the San Fernando Valley, because that was where the other artists lived. The New York show brought him attention in Europe, and in 1971 he had his first solo show there, at a gallery in Dusseldorf, West Germany. He showed a text-and-photo series called Ingres and Other Parables, ten wittily oblique commentaries on art and the art world. At the opening he met a very tall, very thin young man named Antonio Homem and his business partner, Ileana Sonnabend. Homem and Sonnabend liked his work—liked its novelty, its freshness, its humor. They asked if he would be interested in showing with them. He would.

Suddenly, a year out of National City, Baldessari had landed in the mainstream of postwar art history.

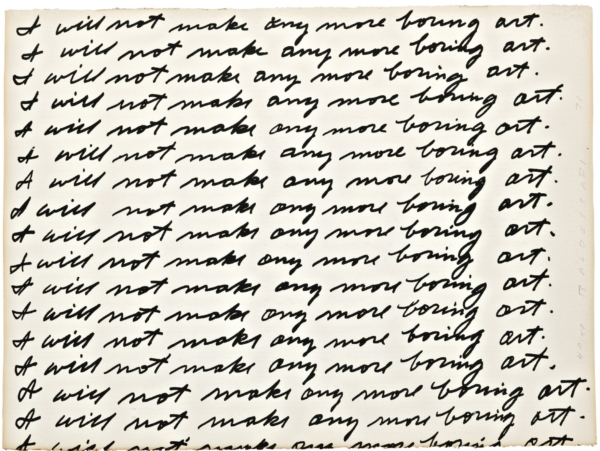

John Baldessari, “I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art,” 1971. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

IN 1941, SHORTLY AFTER the fall of Paris, the 27-year-old Ileana arrived in New York with her husband, the art dealer Leo Castelli. New York seemed hopelessly provincial after Paris, but it would have to do. They settled into an imposing townhouse off Fifth Avenue that had been bought for them by her father, a Romanian industrialist, and hoped for the best. It came. After the war, New York became the center of the art world; the Castellis spent their evenings with Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning—the greats of abstract expressionism. They opened a gallery in 1957 and turned art on its ear with shows by Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, the artists who ushered in the pop movement of the sixties. They rode the pop wave with shows by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein in 1961. After an amicable divorce, Ileana opened a gallery in Paris with her new husband, Michael Sonnabend, and brought their discoveries to Europe. Soon she was known as “the Mom of Pop.”

Today, at 74, Ileanna Sonnabend is a grandmotherly woman whose twinkling eyes and bemused manner disguise her status as the grande dame of contemporary art. Her SoHo gallery, opened in 1971, is associated with some of the hottest names in the neoconceptualist school — names like Ashley Bickerton, the CalArts grad who encases debris-laden ecosystems in black leather, and Jeff Koons, the former Wall Street trader known for his revoltingly kitschy sculptures. “When we opened this gallery,” Sonnabend recalled one afternoon in her pristine white office, “conceptual art was the most difficult, but also the newest and most exciting. It gave food for thought. It was hard for all the artists, because their work was not very accessible and they didn’t make any effort for it to be accessible. But John had a lot of fans.”

“John was a strangely passive, non-judgmental, subversive teacher. He never told anybody what to do; he just destroyed their innocence.”

Most of them were in Europe, where a tiny, elitist art public responded to conceptualism’s intellectual underpinnings; in the United States, where shopping is a national pastime, this kind of thing didn’t wash. So while Americans flocked to museums in ever-increasing numbers to see blockbuster shows of Impressionist and Old Master paintings, conceptualists like Baldessari got teaching jobs to support themselves and spent a lot of time in airports on their way to Amsterdam and Paris and Milan. (One of the great things about conceptualism was that it eliminated the need for shipping charges; you could just fly the artist around instead.) By the mid-seventies, conceptualists had so entrenched themselves in the art schools that they became the dominant force in contemporary art.

Yet if the minimalism that preceded it was dry, conceptualism could be absolutely parched. It purposely avoided any appeal to the sensory experience—what Duchamp called the “visual thrill.” Rather than paint a chair, Joseph Kosuth placed a chair between a black-and-white photograph of itself and a blowup of the dictionary definition for “chair.” Douglas Heubler, weary of producing objects for an already crowded world, played basketball. For a work called Closed Gallery, Robert Barry sent out cards that read, “During this exhibition the gallery will be closed.” Conceptualism was the art-world equivalent of the God-is-dead phenomenon of the sixties: it led art to the abyss.

Then, at the end of the seventies, a hugely ambitious young New Yorker named Julian Schnabel led painting in a bravura comeback. Schnabel’s enormous canvases, gloppy with paint, recalled the myth of the heroic painter as defined by abstract expressionist masters like Pollock and Rothko. This neo-expressionism, as it came to be called, was something collectors could understand. They began to treat art like any other commodity—a development that was carried to an extreme by British ad baron Charles Saatchi, who started buying and selling in bulk. And when neo-expressionism began to fade, a funny thing happened: conceptualism made a comeback—not the dry, uncommercial, academic conceptualism of the seventies but a new version, thinky yet physical, that was as blatantly sales-happy as the old stuff had been self-righteously pure. Many of these artists came out of CalArts; all of them were influenced by Baldessari. And many show their work at the Sonnabend gallery.

Why has conceptualism returned? Smiling coquettishly, Sonnabend said, “Because people have become more intelligent.” She laughed at her own presumptuousness. “Many critics used to say it had to hit you here,” she said, punching herself rather suddenly in the abdomen. “But obviously these things don’t hit you in the plexus—they hit you higher.”

Homem burst out laughing. “Maybe that’s what its all about—periods in which people ask to be hit in the plexus and periods in which they don’t.”

Sonnabend was half-giddy now. “That may be one way of writing art history . . . ‘The tides of plexus and mind.’”

John Baldessari, “Black and White Decision,” 1984. The Broad, Los Angeles.

BALDESSARI MAY HAVE BEEN an academic, but he was never dry. “A pedant with tap shoes,” the critic Kay Larson once called him in New York magazine. In 1971, on being invited to show at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, like CalArts a hotbed of conceptual art (a “coolbed,” he jokes), he devised a work the students could execute themselves. Already disenchanted with conceptualism’s increasing aridity, he suggested that as expiation for their sins they should write on the walls, as many times a they felt like it: I WILL NOT MAKE ANY MORE BORING ART.

At the same time, Baldessari was making every effort, in his deceptively quiet but quite willful way, to pack the CalArts faculty with conceptualists. The school was radical in every respect: there were no grades and no drawing classes, but classes were offered in joint-rolling and witchcraft; legend has it that one painting class held an orgy. When one of the trustees — Madeleine Gilpatric, the ex-wife of a former Kennedy administration official — complained at a board meeting about nude swimming in the pool, a faculty member stood up in front of her and stripped. It was an expensive gesture: the Disney heirs, horrified at what had become of Uncle Walt’s vision, cut back their support. A new president was installed, and fund-raising became his first order of business.

“This little Marxist art school produced some of the most commercial art that’s ever been made.”

The art department retained its conceptualist bent, thanks to Baldessari’s influence. He taught a course called “Post-studio Art,” meaning art you didn’t actually have to execute. CalArts he viewed less as an art school than as an art factory, a notion that fit in with his desire to take art into the realm of the everyday. He led students on field trips to places like the Palace of Living Art near Anaheim, a wax museum where they could see all the greats of Western civilization at work in their studios — Michelangelo sculpting his Dying Slave, Leonardo da Vinci painting the Mona Lisa. “He was trying to take out the Art-with-a-capital-A and get down to the issues,” says Matt Mullican, a 1974 graduate. “He was constantly telling jokes about it — but you got the idea that it was the best thing anybody could do.”

“John was a strangely passive, nonjudgmental, subversive teacher,” recalls Paul Brach, the dean who hired him. “He never told anybody what to do; he just destroyed their innocence.” He brought in people like Robert Barry and performance artist Laurie Anderson — real artists who showed in real galleries and museums — to give students the role models he’d never had. New York gallery owners came too, providing firsthand information on the mechanics of the art world. Students were encouraged, if not ordered, to move to New York when they graduated because that’s where the support structure was. And they learned how to defend themselves intellectually — a skill they turned to devastating effect on visiting artists who didn’t quite have their rap down.

“Confidence,” says Ross Bleckner, a prominent New York painter who got his MFA at CalArts in 1973. “That’s what l felt most there. And a broader perspective about what the possibilities of making art were.”

John Baldessari, “Buildings=Guns=People/Desire, Knowledge, and Hope (with Smog),” 1985. The Broad, Los Angeles.

If anything, Bleckner and his peers gained too much confidence. CalArts graduates soon developed a reputation for an aggressiveness that normal people found unnerving. “It was completely understood that we would all be showing in galleries and museums,” Mullican explains. “We would move to New York, get together and create a movement. It wasn’t talked about, but it was understood.” And it was exactly what they did: within a few years of their arrival, Mullican and several other early CalArts graduates — Bleckner, Eric Fischl, David Salle — were showing with Mary Boone, the savvy young dealer whose aggressive marketing skills helped turn Julian Schnabel into an instant sensation. Today, all are considered major artists.

By the early eighties, with the art market booming and the success of the alumni beckoning them on, CalArts students were demonstrating the kind of careerism more commonly found in medical school. The school’s isolated location on a hilltop overlooking the bionic exurb of Valencia had always encouraged a hothouse atmosphere; the excesses of yuppiedom sent things over the top. Visiting artists and dealers were chatted up for their networking potential when they weren’t being savaged in class. Students tried to build a portfolio and to have a New York gallery lined up by the time they graduated. Baldessari, whose teaching style was always sphinx-like — “I don’t remember him saying anything,” says one former student — retreated increasingly into the background.

Others stepped into the breach, many of them teachers Baldessari had brought in — people like Douglas Heubler, who became dean in 1976, and Michael Asher, a conceptualist who deals with the politics of art production. Asher taught the conceptualist hard line, a Marxist/feminist/structuralist critique that students learned to ignore at their peril, since a cadre of “Asherettes” stood ready to shout down any deviants. “Those were the issues and that was the way in which you were judged and the language you had to speak in order to he taken seriously. It was basically beat into you,” says Mike Kelley, a 1978 graduate who was one of the stars last year’s Whitney Biennial exhibition in New York. “They were always trying to trip you up and make you see how naïve you were,” says Liz Larner, a 1985 graduate who lives in Los Angeles. “Not a lot of people could take it.”

One of his students explains: “It was completely understood that we would all move to New York, get together and create a movement.”

Curiously, the bourgeois careerism of the students fused with the intellectual Marxism of the faculty to produce graduates who tried to have it both ways — to create highly collectible objects that seek to subvert the idea of art as a commodity. “At its worst,” says Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe, a painter who left the CalArts faculty in 1985, “there was an indifference to everything that constitutes a work of art in favor of how to get on in the art world. This was exacerbated and encouraged by people on the faculty who wanted only to talk about how the work functions as a model for capitalist exchange. They only see the work of art as a critique of capitalism — so it’s only about capitalism for them, just as it’s only about capitalism for some Wall Street collector. And this little Marxist art school, because of its Marxism, produced the most commercial art that’s ever been made.”

Baldessari had little sympathy with the intellectual Marxist critique that had come to dominate CalArts; by the mid-eighties, his former colleagues suggest, he’d lost interest in teaching as well. But the final step in his estrangement from the academy he’d created came when his friend Gilbert-Rolfe was dismissed amid an outburst of bitterness and vituperation. The trouble began after Catherine Lord, a radical feminist art critic, was named dean. Lord quickly became a target for Gilbert-Rolfe’s viciously erudite barbs—but it wasn’t just Lord he wished to flay, it was most of the faculty too, “people who have classes in which very, very mad and arcane views of the world are offered as a form of higher education,” in his view. He didn’t limit his remarks to faculty meetings, either; he shared them freely with students. Finally, Gilbert-Rolfe was ushered into a room and told his contract wasn’t being renewed.

“I hated doing it,” Lord says.

The only faculty member to object was Baldessari, who’d won a Guggenheim grant and wasn’t planning to return the next year anyway. “Not that I didn’t find Jeremy as cantankerous as anybody else did,” Baldessari says, “but my attitude was, you hire somebody for their quirks and you can’t fire them for that too. If that went on, soon somebody would censure me for being too tall.”

John Baldessari, “Nearby Fate (with Hinge),” 1987.

ONE WAY OF PUTTING THE DIFFERENCE between Baldessari and the other conceptualists at CalArts was that they, like most professors, expected to teach their students, while he was more interested in what his students could teach him. On one occasion he asked his students to sort a pile of junk he’d picked up at a thrift shop because he wanted to see how they’d categorize it. He grew interested in structuralism for the same reason — because it offered new ways of ordering things, and he was desperate for an alternative to the norm: “alphabetical, color-coding, by height, by weight—anything other than what looks nice.”

For his Blasted Allegories series of 1978 — the title was appropriated from a cry of frustration once uttered by Nathaniel Hawthorne — he randomly photographed images off a TV screen, got his studio assistants to label them with words, filed them away in boxes and then devised elaborate sets of rules that would force him to use the first ones he found, regardless of whether they looked nice together or made any kind of sense. By making up his own rules, he was able to reduce art to an arbitrary system of images, much as structuralists view language as an arbitrary system of signs. He likens it to making choices from a menu by ordering only foods that begin with “p”.

“Anything to escape my own vision!” he cried as we sat in a wine bar on a narrow street in SoHo, sipping zinfandel and discussing the problem of taste. “Life’s got to be more than deciding what color goes next to another color. For some artists that’s fine, but I was more interested in what art was not than what it was. It used to make me furious — who decided what was art and what wasn’t? There are all these things that are excluded. Because of Cézanne, an apple is admitted into the pantheon of art objects. But what about a banana?”

Why was he so interested in what was excluded?

“From art teachers, probably, saying, ‘You can’t do that.’ Or from the world in general saying, ‘You can’t do that.’ I guess at heart it comes clown to the fact that my parents were both European immigrants, and for them there was a right way and a wrong way to do things. My idea was, anything that works. So immediately I bridle when anybody tells me there’s a right way to do something.

“I guess that’s why I never moved to New York. Here you sit around and everybody says, ‘You can’t do that’ because it isn’t historically relevant. Well, who the fuck cares? That’s what I like about California—they have no sense of history, so you just do it.”

John Baldessari, “Studio,” 1988. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

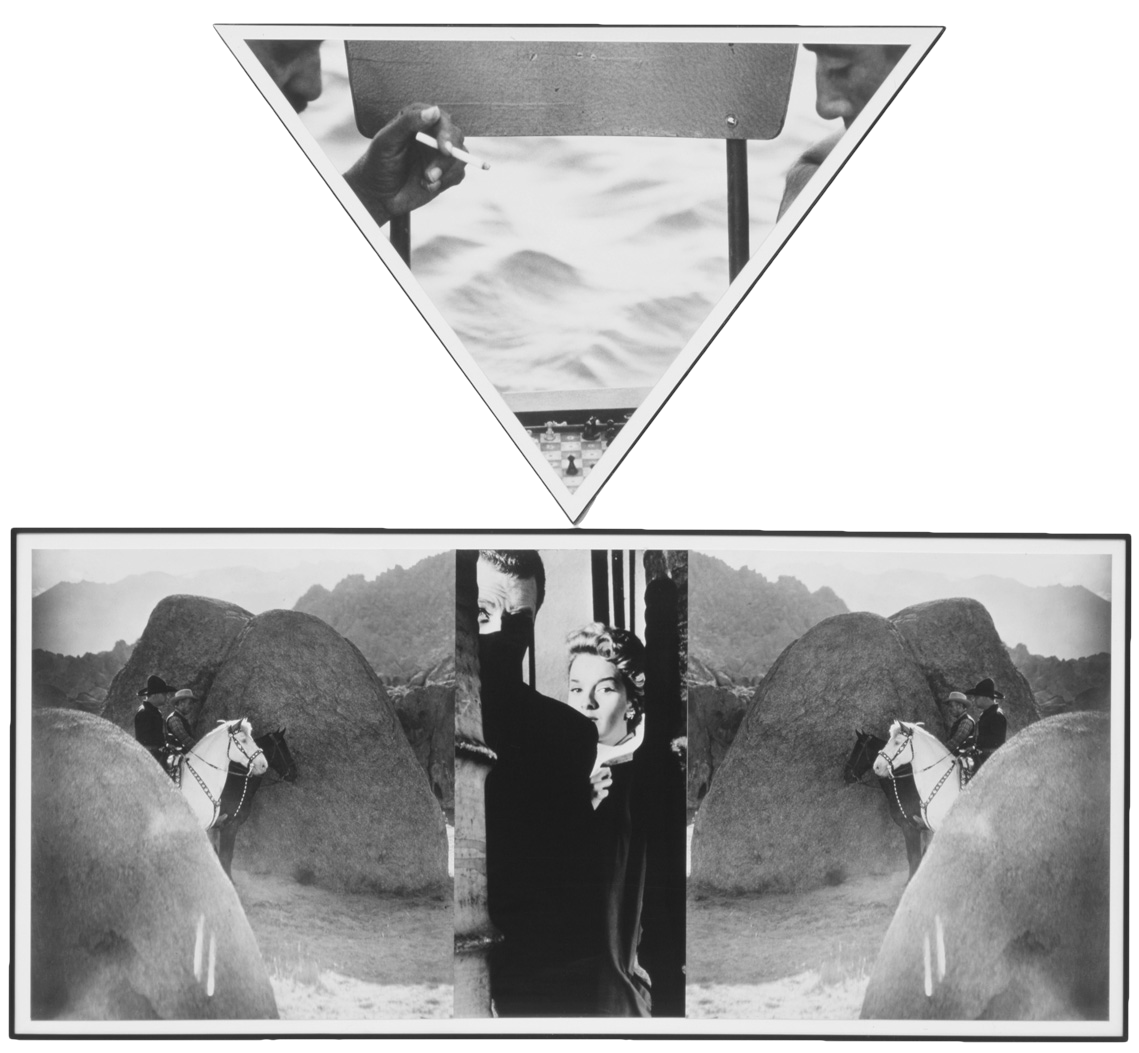

In the late 1970s, Baldessari abandoned intellectual gamesmanship and started making art the way he does now, playing photographic images against each other in ways that are tantalizing, enigmatic and resonant. In a 1984 piece called Starry Night Balanced on Triangulated Trouble, he juxtaposed a rectangular photograph of the night sky — deep, infinite black speckled with tiny spots of light — against a triangular shot of a man in a suit trying desperately to climb into some hopeless space contraption. In Black and White Decision, also from 1984, he used mirror images of Hopalong Cassidy and his sidekick on horseback to flank an old movie still of an anxious couple peering out from behind some oil drums as if cornered. On top of that he balanced a triangular photograph of hands and a chessboard. Danger, desperation, the pressure to make the right move — all transpire beneath the unseen hand of fate.

What’s striking about Baldessari’s current work is how warm it seems, how nonclinical. “John used to be a scientist, exploring aesthetics, exploring language,” says Gary Kornblau, who edits and publishes a new magazine in Los Angeles called Art issues. “Now he’s exploring himself. He’s infusing his art with personal content and not just with some brute aesthetic fact.

“Early on, I don’t know if John ever really let himself into his work. I think the flowering of his art has to do with his becoming more comfortable with who he is. I think that’s what directs the change from the early conceptual stuff to these lush, complicated, beautiful photo-collages. He’s sort of transcended conceptualism. He’s come to terms with the great painterly tradition.”

With Matisse, in other words.

When I asked him about this a few nights later, over dinner in Santa Monica, Baldessari recalled an exchange he’d had in a New York artists’ hangout years ago. It was during the early seventies, the height of the conceptualist challenge. “The lines of battle were pretty clearly drawn,” he said. “There were the painters and the other guys. The painters were in the money and the other guys were written about. They used to call us write-abouts. Anyway, I got into this drunken conversation with Larry Poons” — a minimalist painter of some renown — “and finally I just blurted out, ‘Yeah, but Larry, that would be like wearing your heart on your sleeve!’ And he said, ‘What’s wrong with that?’ And I couldn’t think of an answer.

“It’s just that when you’re cerebral, you’re less vulnerable,” he added. “Up until that time, I thought everything had to be pretty clinical. But that was one of the first seeds of doubt. And at some point I just decided, I’ve done the cerebral routine long enough — now I’ll do the other side. And there I came out at the crossroads of art, because any good art is a combination of both.”

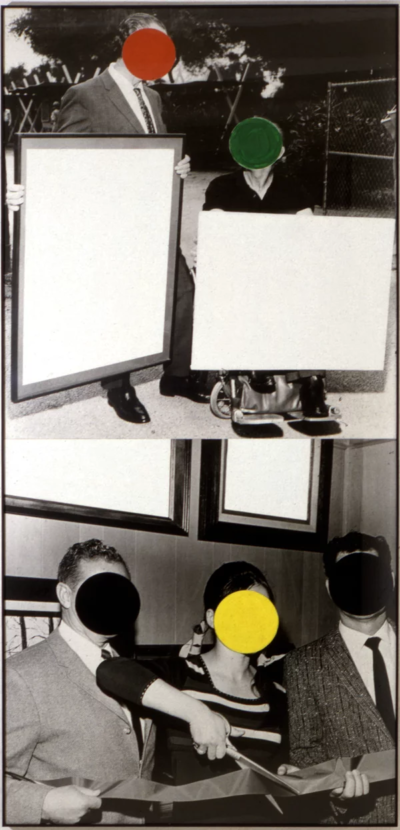

John Baldessari, “Cutting Ribbon, Man In Wheelchair, Paintings (Version #2),” 1988.

It was, of course, the same spot he’d started from, twenty-odd years before. Cézanne and Matisse were his earliest models — the elemental simplicity of the one, the play of color and love of life of the other. If only he could capture them both, he’d thought as he did the paintings that ended up at the crematorium. If only he could do what he’s attempting now.

THOUGH HE WAS LONG A FIXTURE at gallery openings, usually with an attractive young grad student on his arm, Baldessari himself did not have a show in Los Angeles from 1976 until 1984. Even then, nothing sold until the final day. “It was difficult,” says his dealer, Margo Leavin. “John’s work is not easy painting or facile imagery. It took an awful lot of energy.” But by 1986, when Leavin gave him a second show at one of her West Hollywood galleries, things had changed: every serious contemporary collector in town was considering his work, and several came in before the opening to pick out the best. Now, with virtually nothing else available, a dozen or more collectors have joined a waiting list for new works that will be shown this spring.

“I don’t know if John knows there’s a waiting list,” says Leavin, “but it wouldn’t faze him in the least. His response would be, ‘Oh, Margo, how nice for you!’”

It’s nice for him too, of course, for as demand has risen, Baldessari’s prices have escalated accordingly—a process the MOCA retrospective is bound to accelerate. Already, small photo-collages that would have sold for $15,000 six months ago are selling for $25,000 to $35,000; large works are going for $65,000. Speculators have been snapping up existing pieces in expectation of further price increases, provoking a shortage that will only send the numbers spiraling higher.

The consensus among Baldessari’s former students is that California collectors didn’t buy what he was doing earlier because he wasn’t glitzy enough: he didn’t care about the glittering surface, which is what the finish fetish was all about. Nor did he go in for swimming pools — but then David Hockney is derided as a “society painter” by the CalArts crowd. What he did do, through his influence at CalArts, was to ensure that California would play a significant role in contemporary art.

The rise of Los Angeles as a major art center—a conceptualist art center at that—is almost a personal victory. “The finish fetish provided an easy handle, a quick way of identifying what was happening in Los Angeles,” says Richard Koshalek, the director of MOCA. “But that’s faded. I think the emergence of John and his work has given a whole new definition to what’s happened in Southern California.”

There are those who feel that Baldessari is being recognized now precisely because Los Angeles is emerging as an art center. “The economic base here has always been the entertainment industry,” says Mike Kelley, a Detroit-area native who decided to stay in Los Angeles after graduating from CalArts. “There’s never been any interest in the arts. But now there are all these museums, the city is trying to make some money out of it, and they have to look for local heroes. They need major figures to validate themselves, and John Baldessari is a good one to do that with. He’s the figurehead of a whole generation of big artists, he’s associated with a hot school, and he’s here. He’s at the right place at the right time.

Baldessari’s new work is warm, nonclinical. “I’ve done the cerebral routine long enough.”

“It’s been good for me, too,” Kelley adds. “I don’t care what the reason is, I like it. But I’m not naïve about it. I don’t think it’s because everybody’s suddenly interested in art. I know that’s not the case.”

“I think he’s suspicious of the adulation he’s getting,” says a CalArts grad who works as his studio assistant. “The people who are kissing his ass now are the people who wouldn’t answer his phone calls not very long ago. Where were they fifteen years ago?” She laughs. “But I don’t think he’s bitter. He’s just realistic.”

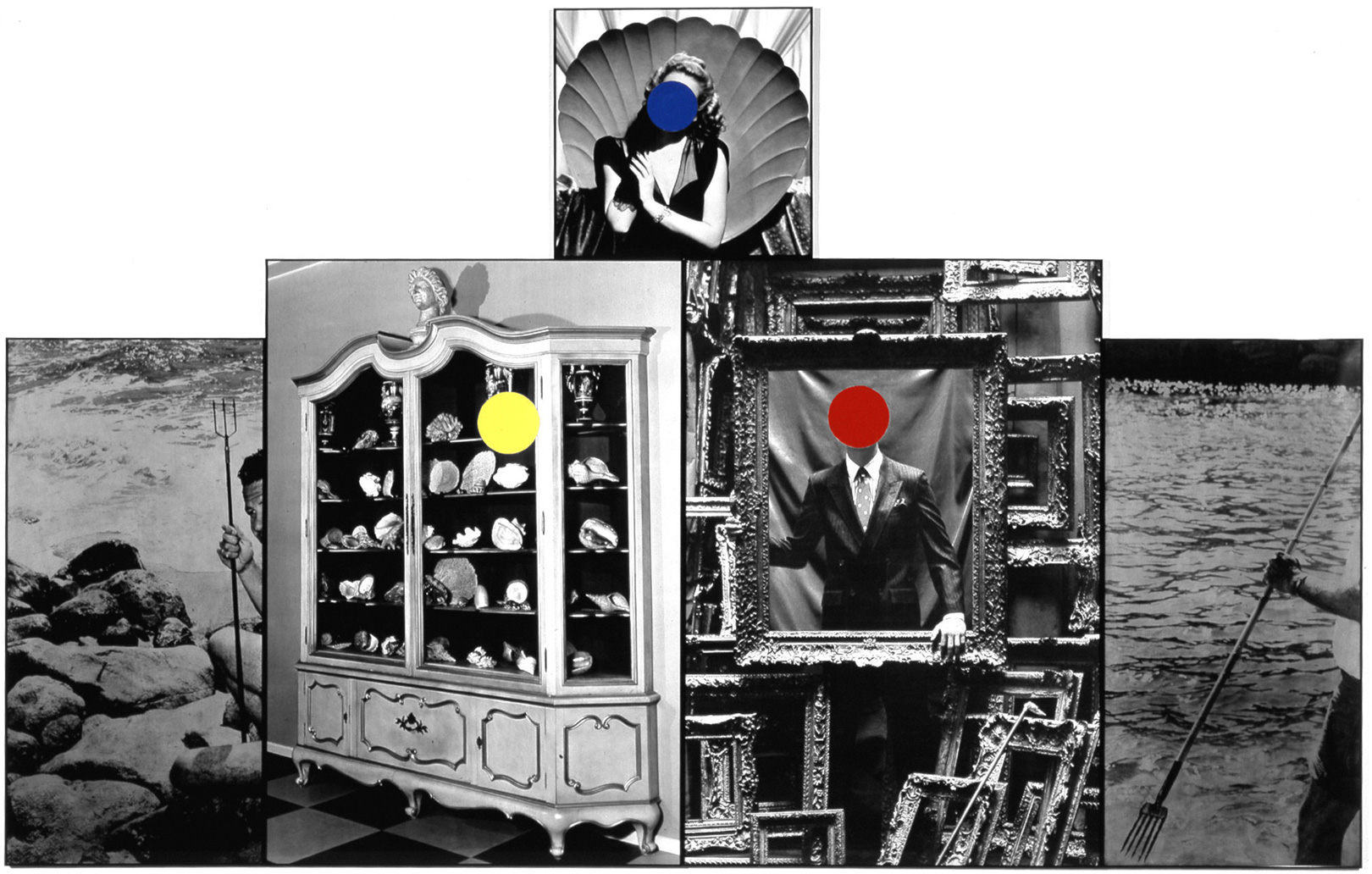

Baldessari’s own comment takes the form of a giant photo-collage on view at the Broad Foundation in Santa Monica. Titled Seashells/Tridents/Frames, it juxtaposes images that suggest great art — Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Michelangelo’s Neptune — with photographs of a man surrounded by empty frames and a French provincial cabinet holding a shell collection. The piece was inspired, Baldessari says, by a collector he’d met, a woman whose art collection was just one of many she’d assembled over the years. She also had a bottle collection, a handbag collection, a comb collection, one after another, and each equally precious. “I loved the idea that it was all the same to her,” he says. “I used to think art was pretty special until then.”

John Baldessari, “Seashells/Tridents/Frames,” 1988. The Broad, Los Angeles.

April 1, 1990

April 1, 1990