FOR A PERFORMANCE ARTIST, Laurie Anderson certainly has been generating a lot of objects lately—records, a book, even a major retrospective that fills up most of the Queens Museum in New York with photos, videos and weird things. Presumably, this is what they mean by “multimedia.” Yet most of it has the look of documentation rather than art, for her art really comes in the form of words—spoken words, set to music and put in visual context. “Language is a virus from outer space,” she says, quoting William Burroughs, in her sweeping performance piece, United States. If so, then she must be a mad doctor, a midnight gene-splicer whose cryptic communiqués from the lab could lead to some unforeseen form of human mutation.

UNITED STATES, Parts I-IV, Laurie Anderson. Brooklyn Academy of Music, February 3-10, 1983

SHARKEY’S DAY. Laurie Anderson. Single and video, Warner Bros. Records, 1984

UNITED STATES, by Laurie Anderson. Harper & Row, 1984

LAURIE ANDERSON: Works from 1969 to 1983. Queens Museum, July 1-September 9, 1984

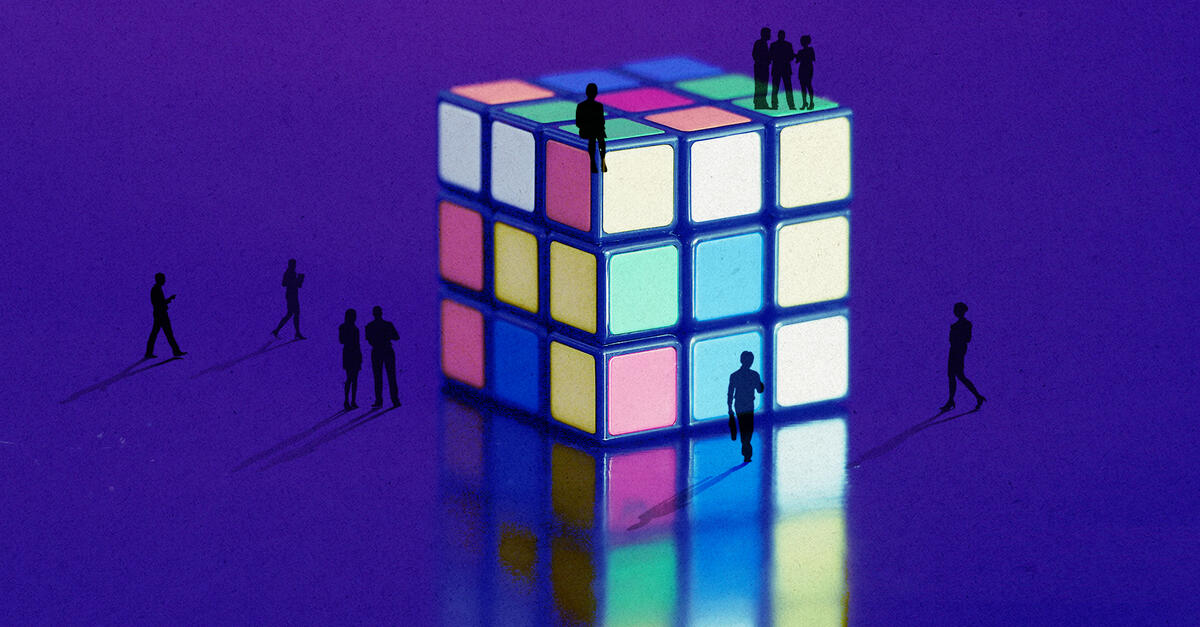

This is all very well timed for the Information Age, and indeed one key to Anderson’s success seems to be the playful way she uses, and comments on, electronic technology. By getting on stage and single-handedly manipulating a lot of complicated electronic gadgetry, she puts herself in command of a technology few of us understand and many are frightened of. Yet her naïve persona—basically she comes across as a highly evolved techno-waif—makes her an immediately sympathetic figure. It’s as if some spiky-haired E.T. had unexpectedly offered to stumble ahead into the future while the rest of us tentatively followed.

The unknown is powerful stuff, of course, but what’s really surprising is how few artists are venturing into the same territory. Computerized music is a lot more compelling than computerized art; that certainly has something to do with it. In general, however, the contemporary art world seems to be backpedaling as fast as it can. If it hopes to gain cachet, any budding movement that doesn’t use spray paint had better have a “neo” tacked to the front of its name. Laurie Anderson is an anomaly in this environment. Despite her popularity, she’s a throwback to the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the art object was dematerializing and it wasn’t outrageous for artists and scientists to look ahead together.

As performance art, Anderson’s work approaches pure information: ethereal, nonlinear, a succession of discrete bits, abstract yet full of content. What she has to say revolves around the love/hate relationship Americans have with nature and technology. In “Sharkey’s Day,” the lead song from Mister Heartbreak, her second Warner Bros. album, she tells the story of a grocery store employee, a middle-aged, Middle American, middle-everything sort of guy who can probably look forward to being the store manager if he stays at his desk another twenty years. Sharkey has strange dreams he can’t quite remember. He views insects and animals with horror: “I’d rather see this on TV. Tones it down.” He takes note of the new mechanical trees that grow to their full height, then chop themselves down. He views life as something that comes out of a swamp and creeps into the house. Animals howl and yelp in the background. Does anybody still wonder why everything in the supermarket is shrink-wrapped or frozen?

Before and After Punk |

A mild-mannered music writer goes to this dive bar on the Bowery. . . |

Why Elvis?The King was just a sweet mama’s boy whose vague dreams of stardom took him places he’d never dreamed of.

|

Minimal and MysticalWhat does “Einstein on the Beach” have to say to us in this post-Minimal era?

|

Laurie Anderson, Multimedia Techno-WaifA spiky-haired extra-terrestrial stumbles forward into the future.

|

A Rotten Success StoryPublic Image Ltd.: Are they committing rock’n’roll suicide, or are they simply boring?

|

Dee Dee Ramone Didn’t Wanna Be a Pinhead No MoreSo the New York rocker who practically invented punk kicked heroin, bought a dinette set, and married Vera, who was, you know . . . normal.

|

Discophobia!Rock & roll fights back.

|

Peter Townshend Gets Old Before He DiesThe leader of the Who has been questioning his role in the youth cult for most of this decade.

|

Elvis Costello Wins Friends and Influences PeopleLast Friday afternoon, the avenger had some explaining to do.

|

Danny Fields Is a Number-One Fan“When I first saw the Ramones I went up to them after the set and—‘You guys are great! You guys are great!’ That’s all I could say.”

|

Four Conversations with Brian EnoHe can look into an interviewer’s face and measure the determination to report something weird.

|

September 8, 1984

September 8, 1984