This profile appeared in “British Rock Lives,” a special supplement to the March 28, 1977 issue of The Village Voice. It was reported the month before, on the same trip to the UK that yielded “How Can You Mend a Broken Group?”, the Bee Gees profile for Rolling Stone. A few months earlier, Eno had been working with David Bowie on his album Low at the Château d’Hérouville in a tiny village outside Paris; by the end of the year he would release his fifth solo album, Before and After Science.

Avant-gardist Eno: never so much a rock musician as an artist using rock as his medium. Photo: Ritva Saarikko

THERE’S A BILLBOARD you’re likely to see if you spend any time in London — a giant photograph of St. Paul’s Cathedral set against the skyline. The photo is not as effective as it might be, since St. Paul’s is surrounded by some of the grimmest postwar construction on the planet. But that’s okay, because what the legend says is grim anyway: “Times change. Values don’t. The Daily Telegraph.”

It’s thinking like this that makes Brian Eno despair for Britain. Eno is the country’s last major avant-garde asset, popular music division, and this April he’s moving to Amsterdam. He has a lot of reasons for leaving — taxes among them — but the basic one is simple. “I want to be in a place,” he says, “where people aren’t always saying, ‘Why are you so happy?’”

You don’t see St. Paul’s from Eno’s flat in Maida Vale, West London. You see a park. Not a great park, like Hyde Park or Regent’s Park or Kensington Gardens, but a small park — the Paddington Recreation Area. There are a couple of football fields in the park, and a large mock-Tudor building and beyond it some gray church spires competing for sky with a couple of dull brick high-rises. Eno likes to sit near the bay window in his ground-floor flat and watch the sunset.

You don’t see St. Paul’s from Eno’s flat in Maida Vale, West London. You see a park. Not a great park, like Hyde Park or Regent’s Park or Kensington Gardens, but a small park — the Paddington Recreation Area. There are a couple of football fields in the park, and a large mock-Tudor building and beyond it some gray church spires competing for sky with a couple of dull brick high-rises. Eno likes to sit near the bay window in his ground-floor flat and watch the sunset.

Right now, however, he is conducting an interview — his third of the day. David Bowie’s album, Low, has just come out, and though his name isn’t even on the cover the British music press is hailing it as an Eno work. Eno doesn’t really like interviews — he didn’t like any of the other rock rituals either, from pubescent groupies to prefab hotel rooms — but like everyone else, he submits. He’s gotten pretty good at it. He says he can look into an interviewer’s face and measure the determination to report something weird. He can also measure the anguish that comes with the realization there’s nothing weird to report. This man, after all, has been touted as the scaramouch of the synthesizer.

Before and After Punk |

A mild-mannered music writer goes to this dive bar on the Bowery . . . |

Why Elvis?The King was just a sweet mama’s boy whose vague dreams of stardom took him places he’d never dreamed of.

|

Minimal and MysticalWhat does “Einstein on the Beach” have to say to us in this post-Minimal era?

|

Laurie Anderson, Multimedia Techno-WaifA spiky-haired extra-terrestrial stumbles forward into the future.

|

A Rotten Success StoryPublic Image Ltd.: Are they committing rock’n’roll suicide, or are they simply boring?

|

Dee Dee Ramone Didn’t Wanna Be a Pinhead No MoreSo the New York rocker who practically invented punk kicked heroin, bought a dinette set, and married Vera, who was, you know . . . normal.

|

Discophobia!Rock & roll fights back.

|

Peter Townshend Gets Old Before He DiesThe leader of the Who has been questioning his role in the youth cult for most of this decade.

|

Elvis Costello Wins Friends and Influences PeopleLast Friday afternoon, the avenger had some explaining to do.

|

Danny Fields Is a Number-One Fan“When I first saw the Ramones I went up to them after the set and—‘You guys are great! You guys are great!’ That’s all I could say.”

|

Four Conversations with Brian EnoHe can look into an interviewer’s face and measure the determination to report something weird.

|

The strain of having to live up to journalistic fantasy is somewhat offset, however, by the prospect of a captive audience — especially a captive audience with a tape recorder. Eno does love to talk. Once, on a promotional tour of the States, he talked to 48 interviewers in four days. He only pretended to answer the questions they asked him, however. What he really talked about was his theories, and, rather than start at the beginning each time, he simply began each interview where he’d left off the one before. “I had a lot of ideas bottled up,” he explains, “and I hadn’t really talked to anyone in a while.”

Right now Eno is talking about how he got interested in cybernetics. It had to do with Cornelius Cardew, Stockhausen’s one-time assistant, a serious avant-garde composer turned Maoist rhetorician, and a pre-Maoist piece of his called The Great Learning. Paragraph 7 of The Great Learning is remarkable. It has very few instructions, but it comes out sounding great every time. Eno spent two years studying this piece; he had to learn cybernetics to understand it. It is basically an exercise in accidents, he points out. It uses the failure of its individual performers as the basis for group success.

Eno says cybernetics is his secret career. Last December he published an article called “Generating and Organizing Variety in the Arts” in a British art journal. The article sums up what he had learned during those two years. It contains sentences like “Suffice it to say . . . that an adaptive organism is one which contains built-in mechanisms for monitoring (and adjusting) its own behavior in relation to the alterations in its surrounding.” Eno is very involved in the concept of adaptive organisms. It is the underlying principle of everything he does.

It is central to Eno’s personality that he would have an underlying principle for everything he does. Like many of England’s rock heroes — John Lennon, Peter Townshend, Ray Davies, Bryan Ferry — he comes from an art school background. Unlike the others, however, Eno and Ferry didn’t discard the intellectualism of the art world; they tried to transfer it to rock. Roxy Music, Ferry’s original vehicle, was a camp/glamour band which attempted to update the very ’60s artiness of the Velvet Underground. But Ferry was more interested in promoting the image of artiness than in actually being arty. Eno wasn’t. He was never so much a rock musician as an artist using rock as his medium. His two prime influences are not even musicians; they’re painters — Tom Phillips, who taught him at the Winchester College of Art in the late ’60s, and Peter Schmidt, who teaches at the Watford School of Art outside London (where Cardew taught before he became a Maoist). Eno began as a painter himself.

He is now twenty-eight. He enjoyed a more or less normal Catholic upbringing in the Suffolk town of Woodbridge, where his father is a postman. At sixteen Eno went to Ipswich Art School, moving to Winchester two years later. There he switched from art to music because he became more interested in procedures than in results. As a composer he found that the procedure and the product (that is, the playing and the music) happened at the same time, implying a much looser link between behavior and the results of behavior. He liked that.

Eno didn’t know he had stage presence until he came to London and joined Roxy. He recorded two albums with them — Roxy Music and For Your Pleasure — before he developed so much stage presence that Ferry had to ask him to leave. Since then, Ferry and Eno have grown still farther apart. Eno has remained experimental; Ferry’s act has hardened into slickness. Eno’s music has become almost sunny; Ferry’s has grown increasingly threatening. Four years ago, Eno dashed onstage in mascara and peacock feathers; now he walks about his flat in blue jeans, flannel shirt, and wing-tip shoes and doesn’t appear onstage at all. The bright colors have washed out of his plumage; what’s left are the mutable hues of a survivor.

Ferry is giving a concert tonight at the Royal Albert Hall. Eno has already given his tickets away, but he will drop me off on his way to a gallery opening. We had reached a tricky point in the interview anyway. Eno was explaining his assertion that art is not self-expression by saying that everything is self-expression. “The idea of art as self-expression,” he says, “seems to pretend that the rest of your life you do something else.” Ergo, art must be something more. But what? The real question, then, is, “What is art?” That requires a lengthy answer, which Eno promises tomorrow.

BRYAN FERRY OCCUPIES THAT PECULIAR SPOT in the rock world where the cultured meets the kinky, where privilege mingles with piss. He stands onstage looking like a coke-fed earl who’s been washed ashore after his yacht broke up in mid-party — the kind of man who would hold out his hand and have a bottle of champagne float into it. His band works almost independently behind him, sweeping him up in its fury, and the threatening urgency of its beat lends a keen edge of terror to his act. When he sings “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” he flashes that edge at his audience: What’ll you do now/My darling young ones?

Ferry is staging a music-hall version of Britain’s final fling. Eno is looking beyond, to the green worlds of tomorrow. There is no menace to his stance, only bright-eyed purpose. The relationship is simple: Ferry poses the problem; Eno suggests the solution.

“Would it be rude,” he inquires the next day, “to say that Bryan Ferry is the problem?” Eno smiles. He points out how stars are by nature nonadaptive and monolithic, how star in German means stiff. He plays some music. He puts on a highlife record by Fela Ransome-Kuti and Africa 70 and remarks that it’s the only music that makes him want to dance. Then he plays a tape he says may be the beginning of a whole new way of working for him. It started as a five-minute take of five people improvising on an earlier improvisation. He edited it down to two minutes and linked unforeseen interactions with synthesizer phrases. Like Cardew in The Great Learning, he’d created a situation in which a narrow range of musical possibilities existed. He’d succeeded in getting the sounds he wanted without specifying those sounds in advance.

Art, to Eno, is not mere self-expression; getting dressed In the morning is self-expression. Art is life in microcosm.

This, he notes excitedly, is the central problem of cybernetics: how to organize systems toward goals you can’t predict. “This is the most exciting bunch of thoughts I have at the moment,” he states. “Everything I do is connected with this.”

Suddenly he stops pacing. He puts his hand to his mouth and swallows. “There’s a big weight of things trying to come out,” he says, looking pale. “I don’t know whether to start on them —”

I try to sound encouraging. He takes a deep breath and begins. He’s talking about cybernetics. He’s saying that cybernetics is the science of organization. Cybernetics shows you how to organize systems too complex to understand, to deal with a world too complex to understand. The function of art is to create conceptual disorientation. Good art breaks rules. It forces people to either accept disorientation or to retreat. If they retreat from life as they do from art, they eventually come to live in the past.

Art, to Eno, is not mere self-expression; getting dressed In the morning is self-expression. Art is life in microcosm. He quotes John Cage: “‘Art is a net,’ Cage said. Years later I read Morse Peckham. He said, ‘Art is safe.’ I realized that’s what Cage meant. You’re creating a false world where you can afford to make mistakes.”

Eno’s experiments have to do with organizing groups of people to make music. Perhaps his most notorious was the Portsmouth Sinfonia, an orchestra of erstwhile non-musicians who tackled the classics with predictably devastating results (proving that, no, you could not fuck with Rossini and expect him to adapt). But Low, the new Bowie album, contains the results of similar experiments. Much of Low is an attempt to abolish the hierarchical structure of musical organizations, and especially the supremacy of vocals over music. Eno explains with the following diagrams — first of an orchestra, then of a rock band:

In a rock band, as he points out, the drifters (e.g., Jagger, Richard) have a high degree of freedom relative to the anchors (Watts, Wyman, et al). In black music, however, the anchors have more weight, so that the rhythm section becomes almost as prominent as the soloists — occasionally even more so. Station To Station did this in a kind of freaked-out R&B context. Low is an attempt to do it in an avant-garde context: The drums are mixed louder than any other instrument, with the bass drum mixed loudest of all; the vocals are nonexistent or lost.

“What if you not only wanted to compress but to shift the focus,” Eno asks, “so that certain things would be drifting in and out? What you’d come up with is this track.” He cues “Subterraneans.” “I think this is fantastic. It’s a milestone for me. I had nothing to do with it, actually, except to encourage David to include it — but he was going to do that anyway. . . .”

It sounds almost Biblical, this put-the-first-last stuff. It also sounds radical. Eno is not unaware of the sociopolitical implications. He is a person, after all, who keeps books like The Military Balance (“who sells what to whom”) and The World In Figures (“really fucking interesting”) on the bookshelf in his breakfast room. He also keeps scrapbooks of newspaper clippings: “Hush Money Charge Hits Mondale,” “Hell’s Angels Protect White Farms” (in Rhodesia), “Lagos Cracks the Whip on Errant Drivers,” and “The War of the Satellites: Pentagon Is Developing Defense Measures Against Soviet Hunter-Killer Spacecraft.” (The space-war headline sets him off on a fifteen-minute discussion in which he terms the idea of ritual wars in space involving unmanned craft “quite interesting.”)

“I wouldn’t exist as a musician without the tape recorder. More than anything else, that’s the instrument I play.”

By reordering the hierarchies and reshuffling the combinations in which people make music, Eno is quite obviously challenging the hierarchies and combinations in which they live. He is too wary to make any such claims directly, however. Instead he retreats into the personal experiment. “I can center all my problems as a person on my problems as an artist,” he says. He also retreats into the spiritual. “Spiritualism is not the promise of a better life but the highest level of discussion one entertains in life — an agreement to partake of a discussion of the largest and most difficult problems. My main problems are, ‘What is really happening? How inaccurate am I? How inadequate am I?’ I realize my map doesn’t fit the real world. Spiritualism is the agreement to deal with this problem.”

RICHARD WILLIAMS, who as an A&R man at Island signed John Cale and Nico, reports a curious statistic: Eno’s British sales went down with each new release, from 35,000 for Here Come the Warm Jets (1974) to 30,000 for Taking Tiger Mountain (by Strategy) (1975) to 18,000 for Another Green World (1976), which is unarguably the best of the lot. Sales for Cale’s three Island albums (the last of which, Helen of Troy, was never released in the States) decreased in similar proportions. On the other hand, Roxy Music has achieved major popularity in Britain and has even established a niche for itself in America.

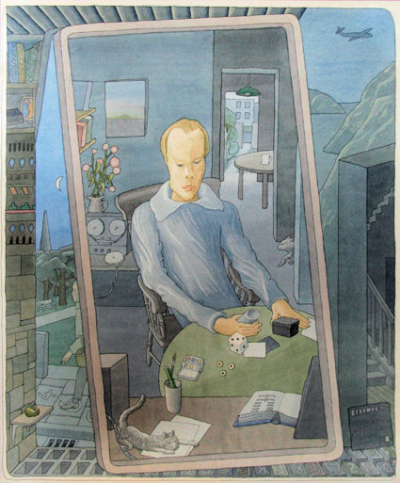

Peter Schmidt, “Portrait of Eno with Allusions.” Watercolor, 1975

The rock avant-garde which Eno once figured in no longer exists. Bryan Ferry has moved to the big stage. Cale has returned to New York, where he’s become a sort of elder in the CBGB underground (he’s managed by Jane Friedman and the Wartoke Concern, who also handle Patti Smith and Television). Richard Wyatt, whose Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard album is a classic, has been confined to a wheelchair since he fell from a window three years ago and has not worked at all since the death last year of his South African trumpet player, Mongezi Feza. There are people Eno still works with — Robert Fripp, Phil Manzanera, and others — but there is no highly visible community committed to translating high-culture principles to a mass-culture idiom.

Punk rock occupies the spot in Britain now that the rock avant-garde did five years ago. It is rock’s “new wave.” (Last month it was even announced that Island Records, having dropped Cale and Nico and lost Roxy and Eno, would distribute Stiff, the new punk label.) But British punk rock, unlike its New York counterpart, is no avant-garde. The zany artistes of the early ’70s have been replaced by a grim assemblage of pseudo-psychopathic rebel/victims who have as much to do with Black Sabbath as with the Velvet Underground.

Meanwhile, Eno lacks an American record company. Island’s budget label, Antilles, has just released Discreet Music, which he recorded some time ago for his own experimental label, Obscure Records; but that’s it. E.G. Records, which packages him, signed with Polydor International last year after its five-year contract with Island expired. That covers everything except the U.S. and. Canada. E.G.’s other acts — including Roxy Music and Bryan Ferry — are all signed to Atlantic in the States, but so far no one has picked up Eno. Eno hardly appears dispirited, however. The deal with Polydor gives him much better European distribution, and his recent collaboration with Bowie has given him renewed notoriety plus a lot of money. “Things have gone very well for me the past two or three years,” he says. “I’m very up all the time.”

This seems to be true. A week after our initial meeting, Eno seems the picture of the happy homemaker — bustling about in his kitchen, scrubbing stove, washing counter, rinsing sink. The place is immaculate. The wall above the counter is covered with ivy, but no soil from the pot sullies any surface. On the stereo is a record by an eighty-three-year-old nearly blind Welsh harpist. It is 11:30 in the morning, and Eno looks as wholesome as a Swiss cereal box. I seem to have entered a miraculous bower.

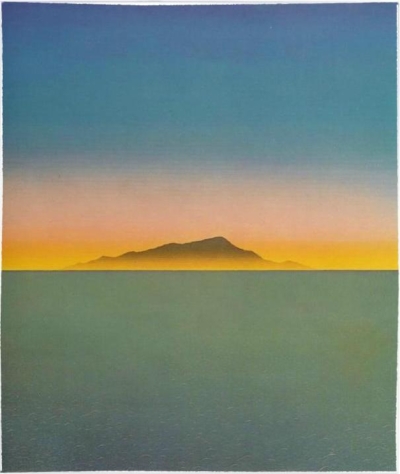

Everything about Eno’s flat breathes a kind of sensuous asceticism. The colors are quiet blues and browns. Objects are at a minimum. Records and books are assigned three shelves; when they threaten to overflow, some are weeded out. In the front room is Peter Schmidt’s painting of a fiery sunset in Tenerife (reproduced on the cover of the Fripp & Eno Evening Star album). Everything else is pallid, unobtrusive, and mutable. Eno mentions the Japanese concept of active space.

Peter Schmidt, “Evening Star.” Acrylic on canvas, 1971-72

There is a bay window in the front room. It divides the room into halves: an inside half, furnished with a carpet, a sofa, and a pile of pillows; and an outside half, furnished with all the accoutrements of the Paddington Recreation Area. When he’s not in the studio, this is where Eno works. He shows me his guitar. He bought it ten years ago for nine pounds and hasn’t changed the strings since. The strings become very dull after ten years, he points out, which is what you want for synthesizer treatment.

“Sometimes I go into the studio with no plan at all,” he says. “Ten minutes before the musicians arrive, I might sit at a piano and find a note I like.” He usually starts with a disposable grid, then builds on that until he achieves some kind of textural completeness. Lyrics come last. He puts a rough mix of the song on the tape machine and jumps around the room singing nonsense syllables until the song is over. Then he replays the tape and tries to make sense of what he sang. “It’s the only way for me to write lyrics, really,” he explains. “I have a feeling for the mood of the song, but I’m not really poetic.”

All this is perhaps best viewed as part of the artist’s ongoing attempt to make use of available technology. “I wouldn’t exist as a musician without the tape recorder,” Eno states. “More than anything else, that’s the instrument I play. It makes sound a plastic medium. You put it on that plastic stuff and instantly it becomes plastic — you can chop it, cut it, do anything you want with it.”

This plasticity is the one quality common to all Eno’s music. It creates a bloodless sound, alien yet undeniably friendly. It is music that reflects warmth but does not seem to generate it. Eno isn’t the only rock synthesizer star to make music like this — it’s the effect they all get, from Mike Oldfield and his tubular bells to Isao Tomita and his dancing snowflakes — but he is the only one to use it without gimmickry. Even Kraftwerk, the German crypto-nostalgics admired by both Bowie and Eno, are locked into a Werner Erhard/Fritz Lang post-industrial schtick. They project the future in terms of the past. Eno does not. Eno uses technological systems to create technological music. He carries no baggage.

Eno’s tracks gurgle with activity. Their rhythm is the pulse of bionic life. But, especially on Another Green World, they also carry a slower pulse. There is a peculiar dynamic between these two beats. It is not simply a case of two rhythms working in tandem; it is more like two metabolisms grappling with each other. Despite the tension, the result is always the same. The slower one always imposes its will, like calm asserting itself.

March 28, 1977

March 28, 1977