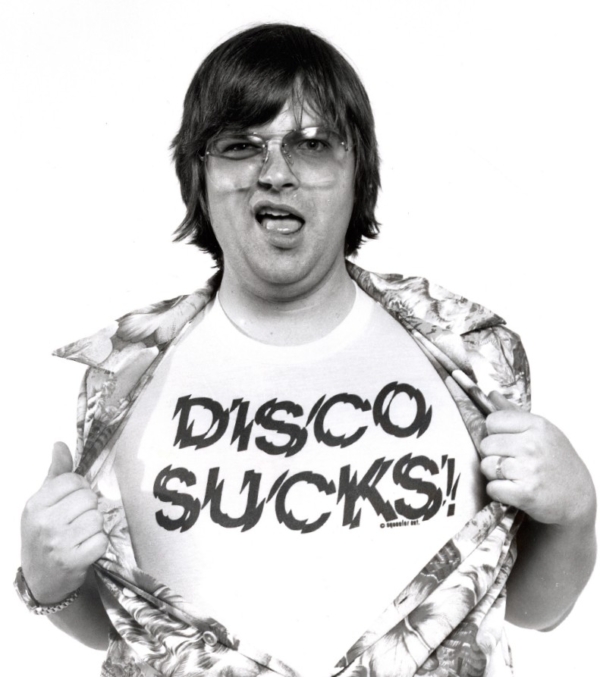

The Comiskey Park riot established Steve Dahl as the godfather of the anti-disco movement.

CONSIDER THE PLIGHT of Chuck Wagon and the Wheels: A Western swing group out of Tucson, Arizona, best known for tunes like “My Girl Passed Out in Her Food” and “We Ran Out of Gas on the Road of Love,” they had it pretty tough last year. Record company indifference forced them to record, press, and distribute their own first album while slugging it out on the Arizona bar circuit; and everywhere they went it seemed like people just wanted to wear gold chains and white suits and dance to that infernal disco beat. Like his cohorts, the 29-year-old Mr. Wagon (real name: Maultsby) objects to disco because of its “pretentiousness” and its “sex overtones”; he doesn’t like expensive fashions and dancing that “looks like a sexual encounter.” Well, things hit rock-bottom one night when this dude stood up in the middle of their set and called for some disco music. So Chuck swung around, nodded to the other guys in the band, and started chanting “disco sucks” as they slipped into a disco beat. The crowd, wouldn’t you know it, went wild.

A year later Chuck and his band still don’t have a big-time record contract, but they do have a song that’s made them celebrities in their home state and gotten them airplay from Santa Barbara to Boston. It’s called “Disco Sucks,” and it’s the hot number on their new LP, Country Swings, Disco Sucks, available on their own Wagon Tracks label. It comes in two parts, the first a perky little swing tune that notes a personal preference for “songs about drivin’ trucks,” the second featuring the aural destruction of a mock disco record in which a Barry White sound-alike moans lasciviously while a female chorus (or could it be the Bee Gees?) chirps “disco sucks … sucks, sucks, sucks.” Chuck and his Wheels have thus parlayed their frustrations into a tune that’s broken the radio barrier and netted them club dates as far away as Chicago and Nashville. And if people call for this instead of their tender country love ballads, so be it. “We don’t care how we get attention,” Chuck told me the other day, “as long as we get it.”

Chuck Maultsby has discovered discophobia.

Before and After Punk |

A mild-mannered music writer goes to this dive bar on the Bowery. . . |

Why Elvis?The King was just a sweet mama’s boy whose vague dreams of stardom took him places he’d never dreamed of.

|

Minimal and MysticalWhat does “Einstein on the Beach” have to say to us in this post-Minimal era?

|

Laurie Anderson, Multimedia Techno-WaifA spiky-haired extra-terrestrial stumbles forward into the future.

|

A Rotten Success StoryPublic Image Ltd.: Are they committing rock’n’roll suicide, or are they simply boring?

|

Dee Dee Ramone Didn’t Wanna Be a Pinhead No MoreSo the New York rocker who practically invented punk kicked heroin, bought a dinette set, and married Vera, who was, you know . . . normal.

|

Discophobia!Rock & roll fights back.

|

Peter Townshend Gets Old Before He DiesThe leader of the Who has been questioning his role in the youth cult for most of this decade.

|

Elvis Costello Wins Friends and Influences PeopleLast Friday afternoon, the avenger had some explaining to do.

|

Danny Fields Is a Number-One Fan“When I first saw the Ramones I went up to them after the set and—‘You guys are great! You guys are great!’ That’s all I could say.”

|

Four Conversations with Brian EnoHe can look into an interviewer’s face and measure the determination to report something weird.

|

Discophobia covers more than just disco music; it takes in the whole disco phenomenon, especially the disco lifestyle. In the past year, discophobia has emerged as the common denominator of all sorts of rock fans, especially big-city punks and those kids who go in for the kick-ass rock & roll of Judas Priest, AC/DC, and Ted Nugent and view themselves as the orphaned heirs to Woodstock Nation. This summer, some of these fans turned mean. In Seattle, they gathered at a fair and menaced a mobile dance floor; in Chicago, they surrounded a van full of dancing girls and chased it out of a shopping center; in Portland, Oregon, they packed the Euphoria Tavern and roared as a radio disc jockey ripped through a stack of records with a chain saw; and in Denver, Detroit, Norfolk, San Jose, and dozens of other cities, they cheered as the alien beat was obliterated by the sound of bombs exploding, elephants stampeding, people puking, or a needle being ground into vinyl. Disco sucks; rock & roll fights back. People are calling it a backlash.

Rock fans say disco sucks because it’s “mindless” and “repetitive,” because it’s “plastic” and synonymous with gold chains and polyester, perfect hair, pulsating lights and sex, sex, sex. Also, it comes from New York. It is spread via media image. It is monolithic. This is how it works: Impressionable young things in the heartland watch John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever and think it’s cool to jump around in three-piece suits; they stop listening to rock music. Club owners look at People magazine and see lines outside Studio 54 and Halston and Bianca rubbing tushes inside; they “go disco” and kick rock bands off their stages. Radio executives look at the amazing Arbitron figures of WKTU-FM, which shot from almost nowhere to number one in the New York market within four months of going all-disco, and conclude that the same formula will work in (your town). Rock stars see disco records topping the charts and decide to cut a hit the easy way. For a time last spring, it began to look as if disco might actually take over America. Like defenders of the nuclear family, rock fans felt their backs to the wall. They imagined themselves in extinction, and they started lashing out.

Their generally acknowledged leader is 24-year-old Steve Dahl, the Chicago deejay whose sponsorship of the notorious disco demolition derby in Comiskey Park last July 12 made him the godfather of the anti-disco movement. It was the Comiskey Park riot, in which several thousand rock fans poured out of the stands and lit bonfires after Dahl blew up 10,000 disco albums between games at a Chicago White Sox/Detroit Tigers doubleheader, that revealed discophobia’s potential for getting seriously out of hand. It was FM rock radio that, months earlier, discovered disco destruction’s potential for building a movement and, in the process, boosting ratings. Dahl’s experience was prototypal: Departed from ABC-owned WDAI-FM when it dropped its old AOR (album-oriented rock) format and went disco a couple of days before Christmas 1978, be resurfaced in March as the morning man on WLUP-FM and immediately started lashing out against disco. (A coworker says he was especially bitter about the Christmas thing.) Like many of those who have followed his lead, Dahl is more “air personality” than anything else; and whenever he turned the 15-minute lunatic stream-of-consciousness raps he does between songs into disco-baiting monologues, he couldn’t help noticing how the phones lit up.

Pretty soon he was urging listeners to send in a “stomped, self-abused envelope” so they could get membership cards in his “disco destruction army,” the Insane Coho Lips, which he has “dedicated to the eradication of the dreaded musical disease known as DISCO.” (Coho salmon are celebrated in Chicago for having rid Lake Michigan of the lamprey eel, a slithery parasite that had almost succeeded in wiping out the lake’s edible fish.) WLUP had to hire two people full-time just to handle the mail. In early June, when a disco in suburban Linwood switched to rock & roll and Dahl showed up for the festivities, nearly 5000 followers turned out and police had to be called in from Indiana. Later, when Dahl urged listeners to throw marshmallows at a WDAI promotional van at Dearbrook Mall, they ended up cornering it at a nearby park, where the driver had to talk his way out of the first potential disco hostage situation.

This aroused some concern, but the Comiskey Park promotion went on regardless, and when Arbitron’s July-August book came out it showed “the Loop,” with its hyped-up format of hard-ass rock & roll, seizing the number-three spot from WLS, the top-40 AM station that has been the city’s traditional youth market leader. Dahl has gone on to become an Ovation recording artist, having cut a Rod Stewart parody called “Do You Think I’m Disco?” (“Am I superficial?”) with the band that played in Linwood, who go onstage in yellow boots, yellow slickers, and hardhats and call themselves “Teenage Radiation.” Asked how he feels about disco destruction today, Dahl replied, “Well, it worked real well for me. And I think it made a lot of people sit back and question the disco stuff that was being shoved down their throats.”

Dahl is not, as many assume, the actual inventor of disco destruction. The gimmick itself is ancient: Scott Muni, now program director of WNEW-FM, was breaking records on WMCA’s “Make It or Break It” listener call-in show in 1959. WPIX-FM kicked off its “pure rock & roll” format this past January with “record-breaking weekends” that featured the destruction of disco hits as well as the MOR tunes of people like Barbra Streisand and Johnny Mathis. Deejay “Dennis Erectus” of station KOME-FM in San Jose was doing disco destruction six months before that. The 30-year-old Erectus, whose show is laced with a sexual innuendo that dovetails neatly with the station’s image (promo spots advertise it as “the KOME spot on your dial” and ask, “Have you KOME today?”), started on disco records after listeners went nuts for a promo that claimed the station actually caused the 1906 earthquake by playing a Kiss record too loud. (During the promo the needle jumped around.) They called it “Erectus Wrecks a Record”: He’d play a couple of bars, then crank the turntable up to 78 rpm (especially effective on “Macho Man”), grind the needle into the vinyl, play sound effects of toilets flushing or people throwing up, and follow it up with the searing guitar chords of Van Helen or AC/DC. Pretty soon he was doing it in person at nightclubs and area high schools. “It’s quite a release,” he confided. “Sometimes I just get a lightheaded feeling while I’m doing it.”

When Chicago deejay Steve Dahl blew up 10,000 disco albums at Comiskey Park, rock fans poured from the stage to light bonfires, rampage, and generally illustrate discophobia’s potential for getting out of hand.

Dennis Erectus notwithstanding, it wasn’t until Steve Dahl that disco destruction really caught on as a promotion gimmick. By midsummer—summer is a big time in rock radio because of the hordes of kids who go places and take their radios with them—it was being done all over the country. At WLVQ-FM, in Columbus, Ohio, morning man John Fisher put on fatigues and a gas mask, declared himself general of a rock & roll army, torpedoed the Village People’s “In the Navy,” and sent uncounted hundreds of disco records to the trash compactor between periods at a soccer match. At KGON-FM in Portland, Oregon, morning man Bob Anchetta followed his chain-saw demonstration at the Euphoria Tavern by smashing and burning hundreds more on top of the concession stand at the 104th Street drive-in for a crowd of 900 who chanted “disco sucks” while waiting to see Animal House. At WOUR-FM in Utica, listeners were given three possible means of destruction every morning—for instance, chainsaw, city bus, or wild-animal stampede—and forced to endure a disco record until someone called in with the means of destruction that had been chosen for it; then the record would be bussed to death, say, and the winner would receive a shard along with a rock record and a little commemorative plaque. At WWWW-FM in Detroit—popularly known as W4—morning men Jim Johnson and George Baier set up an anti-disco vigilante group they decided (“without thinking too deeply,” Baier now admits) to call the Disco Ducks Klan. They were planning to wear white sheets onstage at a disco that was switching back to rock when the Comiskey Park riot persuaded them to cool it. It turned out that on the day it was supposed to have taken place, they left W4 for another AOR station, WRIT-FM, where they now run an organization called DREAD (Detroit Rockers Engaged in the Abolition of Disco) and hold on-the-air “electrocutions” of disco-lovers whose names and phone numbers have been sent in by the DIA (DREAD Intelligence Agency), One listener sent them a realistic-looking prop; they call it the John Spenkelink Electro-Boy Chair and use it in personal appearances, claiming it was imported from Florida.

The rapid spread of disco destruction may have seemed spontaneous to outsiders, but it was actually the handiwork of Lee Abrams of Burkhart-Abrams Associates, an Atlanta-based radio consulting firm. Abrams handles 53 AOR stations; his partner, Kent Burkhart, consults for a slightly smailer number of stations, all of them top-40, country, or disco. Burkhart and Abrams are credited with developing the concept of “modal programming,” which means embracing one form of music, such as disco or hard rock, on an all-out, 24 hour-a-day basis and pounding it to death. (Ironically, it is the advent of the modally programmed disco station exemplified by WKTU that is blamed for much of the anti-disco backlash). Abrams began consulting for WLUP about the same time Steve Dahl started working there, and last May he advised his other clients that Dahl had discovered a remarkable new tool. He says most of his stations thought it was a fun promotional idea, but that some stations didn’t handle it properly.

Abrams did not base his recommendations on Dahl’s experience alone; he also relied on the findings of John Parikhal of Joint Communications, an independent media-consulting firm in Toronto. Parikhal is the consultant to the consultant. He appears to be the only person who has done attitudinal research on discophobia. First, he assembled three 10-person “focus groups” of 15-to-25-year¬olds in Toronto and got them to verbalize their feelings about disco; he followed that with 6000 questionnaires in three markets, one of them in Canada, two in the States. He found everyone in the focus groups fairly neutral at first, but then a couple of people would come out hard against disco, and pretty soon everybody would join in. (Parikhal says this often happens when peer pressure gets so strong that “issue orientation” gives way to “event orientation”: As with campus protests in the ’60s, people start joining in simply to be where the action is.) They thought disco was superficial, boring, repetitive, and short on “balls.” (Parikhal says this is a reference to the “homogenized” nature of disco compared to the aggressiveness of rock.) They were also intimidated by the lifestyle—partly by its emphasis on physical and sartorial perfection, partly because its atmosphere is so charged with sex.

Parikhal has reached several conclusions. He considers the anti-disco movement a pro-rock movement which states itself negatively because we are in a negative period in our culture. As the energy crisis deepens and people feel their lives slipping increasingly out of control, he expects the search for scapegoats to widen: Disco will simply be the first of many. Other likely candidates include anything suggestive of high technology, since people all over the world are currently engaged in a love-hate relationship with technology (Star Wars fantasy vs. gas panic reality) that coincides with their growing feeling of enslavement to it. The antinuclear movement can be seen as part of the same phenomenon.

Asked about the proper role of radio, Parikhal hedges. “There are very divided opinons on that,” he says. “It’s a question of whether you look at it from a ratings standpoint or from some other standpoint.”

The Insane Coho Lips are Dahl’s “disco destruction army.”

November 12, 1979

November 12, 1979