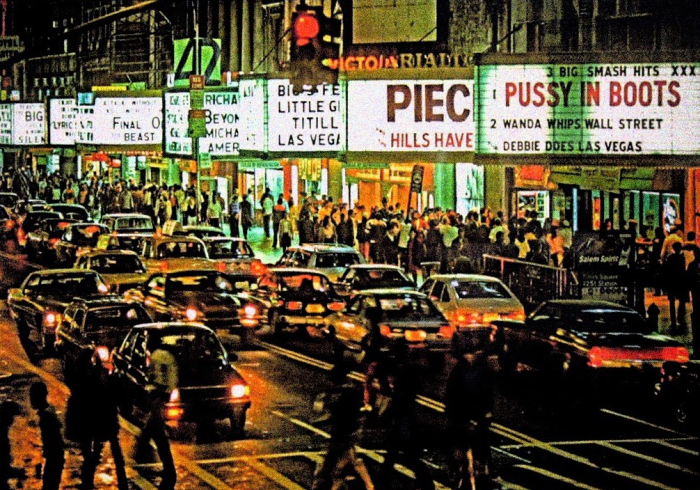

DISNEY ON 42ND STREET? The mind boggles. In February 1994, when the Walt Disney Co. announced it would be staging theatrical productions on “the Deuce”—the porn-plagued, drug-infested, crime-ridden block of 42nd Street between Times Square and Eighth Avenue in Manhattan—pundits took it for a joke. A full-page New Yorker cartoon had Bart Simpson smoking dope and Betty Boop running for her life beneath billboards touting the Aladdin Hashish Emporium, Goofy’s Massage Parlor, and Mickey Mouse and Daisy Duck in Hot Lips (Unfeathered Version). Then there was David Letterman’s top ten list of upcoming productions: Hookers of the Caribbean, Beauty and the Bobbitt, . . .

But Disney chairman Michael Eisner didn’t see it that way. From Team Disney headquarters in Burbank, 42nd Street wasn’t the den of depravity it had become to New Yorkers; it was the Main Street U.S.A. of show business, complete with its own jingle from the 1933 Busby Berkeley musical. “I think the Disney brand is going to be enhanced by being on 42nd Street,” Eisner insists. “It’s a magic word and a magic place.”

With the last of the peep shows now shuttered and the marquees that once advertised XXX adult features coming down, Eisner may have the last laugh. For $36 million—most of it in state and city loans at 3% interest—Disney is getting the showplace of Broadway, a turn-of-the-century fantasy setting for signature productions like Beauty and the Beast. Better yet, the landmark New Amsterdam Theatre will be the centerpiece of one of the most intensively developed entertainment strips in the world, a $1.8 billion complex of theaters, cinemas, stores, restaurants, game parlors, offices, and hotels flanking Times Square. Though most of the block now lies eerily deserted, beneath their patina of neglect the street’s once dazzling theaters lie strangely untouched, as if waiting for their moment. Sleeping Beauty metaphors come to mind.

When Disney planners first saw 42nd Street, their initial impulse was to gate it. They forgot that just across Eighth Avenue is the Port Authority Bus Terminal, a point of entry for 180,000 daily commuters.

For Disney, which last year (before its $19 billion acquisition of Capital Cities/ABC) earned $1.4 billion on $12 billion in revenues, the investment in 42nd Street is negligible financially. In terms of visibility, however, it ranks not too far behind buying Cap Cities and hiring Michael Ovitz as president. It’s also significant strategically: A company known for developing vast, greenfield theme parks is venturing into a brownfield site long cursed with one of the highest crime rates in Manhattan.

CERTAINLY THERE’S IRONY IN DISNEY, the quintessential merchandisers of pop-culture innocence, coming to 42nd Street, which even in its heyday was everything Walt was not. One fact captures the gulf between Disney and New York: Three years ago, when Disney planners first looked at 42nd Street, their initial impulse was to gate it. They forgot that just across Eighth Avenue is the Port Authority Bus Terminal, a point of entry for 180,000 daily commuters. “We do have some genetic instincts,” admits a sheepish Peter Rummell, chairman of Walt Disney Imagineering. “But then we realized that half of New Jersey has to travel 42nd Street to get to work.”

A Decade of Reporting on the Global Media Conglomerates |

In the 1990s and into the 2000s, a series of ego-fueled mega-mergers led to the creation of six global media conglomerates: News Corp., Sony, AOL Time Warner, Vivendi Universal, Viacom and Walt Disney. For most, it would not end well. |

Can the PS3 Save Sony?The company that created the transistor radio and the Walkman is at the precipice.

|

Barry Diller Has No Vision for the Future of the InternetThat’s why the no-nonsense honcho of Home Shopping Network and Universal is poised to rule the interactive world.

|

The Civil War Inside SonySony Music wants to entertain you. Sony Electronics wants to equip you. Too bad their interests are diametrically opposed.

|

Big Media or BustAs consolidation sweeps the content and telecom industries, FCC Chairman Michael Powell has a plan: Let’s roll.

|

Vivendi’s High Wireless ActWill a global media company with continent-wide mobile distribution prove unbeatable?

|

Reminder to Steve Case: Confiscate the Long KnivesTime Warner brings fat pipe and petabytes of content to AOL—plus a long history of infighting and backstabbing.

|

Think Globally, Script LocallyAmerican pop culture was going to conquer the world — but now local content is becoming king.

|

Edgar Bronfman Actually Has a Strategy—with a TwistThe Seagram heir is challenging Disney in theme parks and spending billions to be No. 1 in music. Can this work?

|

There’s No Business Like Show BusinessA handful of powerful CEOs are battling for the hearts, minds, and eyeballs of the world’s six billion people.

|

What Ever Happened to Michael Ovitz?Striving to make his comeback, CAA’s superagent is now an unemployment statistic. Seven lessons to be learned from the fall of the image king.

|

Can Disney Tame 42nd Street?Disney is pouring millions into one of Manhattan’s most crime-ridden blocks. What does Michael Eisner know that you don’t?

|

Twilight of the Last MogulLew Wasserman has been shaking Hollywood since the ’30s. When Seagram bought MCA, was he really out of the loop, or was he king of the dealmakers to the last?Los Angeles Times Magazine | May 21, 1995 |

The question for Disney is, Will America travel 42nd Street to play? The Rouse Co.’s success with “festival marketplaces” in cities like Boston and Baltimore augurs well. Disney executives—who seem more preoccupied with ABC’s entertainment problems than with 42nd Street’s—won’t discuss financial expectations for Times Square or for similar efforts they’re planning elsewhere. But at least they’re not expecting another Disneyland Paris—which lost $1.3 billion in its first 30 months, thanks to poor planning, overbuilding, inept marketing (a French resort without wine?), rising interest rates, high prices, and lousy weather. “The only jeopardy for us,” says Rummell, “would be if urban entertainment got so big that people said, ‘We don’t have to go to Walt Disney World this year.’ This is designed to be an alternative, not a substitute.”

There are other jeopardies, of course. Exposure on 42nd Street could tarnish the Disney brand—a possibility Eisner brushes aside impatiently, and one the company has gone to great pains to eliminate. Or Disney could damage 42nd Street, slicking it up with the ersatz charm of Universal Studios’ CityWalk, the $100 million urban simulacrum in Los Angeles. Or the street’s appeal could fade as crime worsens and technology makes the couch-potato life ever more enticing.

Disney is betting that won’t happen. “People want to be with people,” says architect and Disney board member Robert A.M. Stern. “Why do we think Starbucks is such a success? Don’t we think you can make coffee at home?” As for crime, that can happen anywhere. When CityWalk opened three years ago, MCA executives heralded it as the safe-shopping alternative to Melrose Avenue, the real-life street of trendy boutiques and upscale restaurants: “I don’t need the excitement of dodging bullets to go there,” CityWalk’s leasing agent said of Melrose. CityWalk has since become known as a gang hangout; last year one of its garages was the scene of a grisly double murder on Mother’s Day. A vibrant urban environment, some argue, is actually safer than a synthetic, isolated one. “There’d have to be a hell of a lot of hooligans to take over midtown Manhattan,” Stern maintains.

THOUGH DISNEY IS OFTEN VIEWED AS A PREDATOR, it was Stern—polished and urbane, his pinstripes set off by the subtlest of Mickey Mouse ties—who led the company to 42nd Street. With six theme parks operating around the world and a seventh killed by opposition (Disney’s America, the animatronic historyland set for the outskirts of Washington, D.C.), the move has a certain logic. As Stern puts it, “How many theme parks can the world have?”

Forty‑Second Street is like no other in the world. River to river, it’s studded with landmarks: the glass-and-marble United Nations headquarters, the art deco Chrysler Building, Grand Central Terminal, the New York Public Library, the bustle of Times Square. At the juncture of Broadway and Seventh Avenue, just after the turn of the century, show business as we know it took form. Sophie Tucker, “the last of the red-hot mamas,” debuted at the New Amsterdam in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1909. William Morris, vaudeville impresario and founder of the talent agency, introduced Charlie Chaplin at his now-demolished American Music Hall; in the audience was Mack Sennett, an aspiring director who resolved to put Chaplin in pictures. Marcus Loew, who went on to form Loew’s Inc. and its Hollywood subsidiary, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, soon took over Morris’s theater, while Loew’s former partner, Adolph Zukor, moved into the building now known as 1 Times Square to form the company that eventually became Paramount.

Then talkies and the Depression hit, and 42nd Street, once dominated by vaudeville and legitimate theater, grew chock-a-block with burlesque houses, flea circuses, and cut-rate movie palaces. In the Fifties, as the middle class fled to the suburbs and stayed home to watch television, the area turned increasingly seedy; by 1969, when Dustin Hoffman played down-and-out “Ratso” Rizzo in Midnight Cowboy, it was synonymous with sleaze.

Urban renewal schemes came and went. In 1987, when Times Square seemed about to be paved with enormous office towers, Stern was commissioned to figure out what to do with the theaters that lined 42nd Street. Because of Eisner’s close ties to the city—he grew up on Park Avenue and started out as a page at NBC—Disney emerged early on as a candidate to help redevelop the block. But when Stern, who’d once designed an East Side penthouse for Eisner’s parents, mentioned the street to Eisner, he was told to come back in ten years.

By this time, the real estate market had collapsed and the office towers seemed dead. Then Stern went to work on another plan. Earlier schemes had relied on office construction to “clean up” the area; Stern wanted to use tourism and entertainment to return 42nd Street to the hurly-burly of its apex. To redevelop the theaters, the state and city formed a private, nonprofit corporation and got New York Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr.—whose headquarters overlooks the sleaze—to persuade his aunt, civic activist Marian Heiskell, to chair it.

Heiskell, a formidable woman who has known Eisner since he was 4, got no further with him than Stern had. Once, seated next to him at a dinner party at the Eisners’ house in Beverly Hills, she even pulled out a map and said how wonderful it would be if Disney came to New York. He demurred, although he did send a couple of people to look at the block. “He was being polite,” Heiskell says now. “He had said all along that he didn’t want to be involved in cities.”

Through the gloom they could make out something that had been described in its day as “a glance into fairyland.” Eisner was enthralled: “I could see what a spectacular place it had been and could be.”

Something else Eisner didn’t want to be involved in: Broadway. Disney executives had considered staging theatrical productions even before Eisner took over as chairman in 1984. He rejected the idea: too risky, and not the core business. Instead, he and Disney Studios chief Jeffrey Katzenberg focused on reviving the company’s slumbering film and television operations and, with Roy Disney, on reestablishing its tarnished name in animation. But with the phenomenal success in 1991 of Beauty and the Beast, their thinking changed. Suddenly Disney had the highest-grossing animated feature of all time; it also had years of experience putting on shows at the theme parks. Stage productions seemed like a good way to leverage the brand.

A new operation was set up in the film division: Walt Disney Theatrical Productions, headed by Bob McTyre, a theater veteran who’d spent years running entertainment at Disneyland. But when McTyre started looking for a theater, he found many of the choicest venues occupied by other long-running musical spectacles—most of them, it seemed, by Andrew Lloyd Webber. So for much the same reason Disney later bought Cap Cities/ABC—to guarantee a distribution channel—it started scouting Broadway real estate.

One day in March 1993, Eisner was in Stern’s office when he asked what was happening on 42nd Street. Within 20 minutes, Stern’s assistants had assembled a model of the entire block. Eisner said he’d like to see the New Amsterdam. The next morning, armed with flashlights and hardhats, the two ventured into the abandoned theater. They stumbled into something out of the Indiana Jones ride at Disneyland: grand hallways reduced to a water-soaked ruin, stairways half buried in rubble, mushrooms growing out of the floor, a soaring playhouse inhabited by birds. Through the gloom they could make out something that had been described in its day as “a glance into fairyland.” Eisner was enthralled: “I could see what a spectacular place it had been and could be,” he says now.

Stern and Eisner took off for Orlando. From the airport, Stern phoned Rebecca Robertson, president of the 42nd Street Development Project, the state agency in charge of the block. “Rebecca,” he said, “do whatever you have to to get these people.”

Robertson phoned Burbank. She learned that Disney had two immediate concerns: Could the seating be expanded from 1,600 to 1,800? And was restoration actually feasible? Within days she’d hired Tishman Realty & Construction, the New York firm that built the World Trade Center and renovated Carnegie Hall, to do a cost estimate.

Before and after: The reception room 42nd Street’s New Amsterdam Theatre as Michael Eisner first saw it and after it was restored. Photos courtesy Evergreene Architectural Arts

DISNEY AND TISHMAN GO WAY BACK. Tishman built Epcot Center and the Hilton at Walt Disney World Village, and it was about to start another hotel when Eisner took command in 1984. An architecture buff from childhood, Eisner quickly shook things up in Burbank by suggesting that a hotel they were thinking about building there be done to look like Mickey Mouse. He was not impressed with the standard-issue box Tishman was planning for Disney World.

Out of the ensuing flap was born “entertainment architecture”—the idea that buildings should be iconic, that they should tell a story, that they should entertain people. “What Michael is trying to do is make every building say something about Disney culture,” explains Stern. In Orlando, that meant hiring Michael Graves to turn Tishman’s box into the Dolphin and the Swan, a $375-million-plus hotel complex graced with Busby Berkeley perspectives, fantastically outsize statues, and shell-shaped fountains.

More commissions followed—office buildings at Disney World for Stern and Arata Isozaki; hotels and other structures at Disneyland Paris for Stern, Graves, and Frank Gehry; the Team Disney building in Burbank for Graves. Always the emphasis was on fun. “Michael Graves designed a very nice building” for Team Disney, recalls Wing Chao, Disney’s master planner. “Michael Eisner looked at it and said, ‘How can you make us smile?’” The next time he saw the plans, the pediment of Graves’s severely neoclassical structure was supported by seven 19-foot-high dwarfs.

In the New Amsterdam, with its extravagant art nouveau decor—Wagnerian friezes, sylvan wall reliefs, allegorical murals of Drama and Virtue and Courage—Disney had stumbled onto one of the most remarkable examples of entertainment architecture anywhere. For Beauty and the Beast, a musical fairy tale set in an enchanted castle, a more suitable venue could hardly be imagined. Could Tishman revive it at a reasonable cost? Tishman thought so, although Disney’s Rummell wasn’t looking forward to it: “Have you ever rehabbed your kitchen? Just think about this as a very, very big kitchen rehab.” And the New Amsterdam was only half the challenge. “My reaction was, fabulous theater,” says David Malmuth, the Disney Imagineering executive who took charge of the project, “but the street needs a lotta help.”

In fact, despite its woebegone appearance, the street had a lot going for it. Tourists, for one thing—some 20 million a year, flocking there to see they knew not what, yet eager to feel, to experience, to spend. A newly opened Gap store at 42nd and Broadway was reportedly in the top percentile of Gap outlets in Manhattan, with two-thirds of its sales to tourists. The McDonald’s at 46th and Seventh, just above Times Square, was one of the three highest-grossing in the country. And with most of 42nd Street boarded up, crime on the block was falling dramatically even as pedestrian traffic was rising.

Making an entrance: The New Amsterdam’s grand foyer is an Art Nouveau fantasia. Photo courtesy H3

IN SEPTEMBER 1993, city and state officials unveiled Stern’s latest plan, which called for a cacophonous mix of loudspeakers, giant billboards, and flashing neon to draw crowds late into the night. Where the office towers would have forced Times Square into a corporate straitjacket, Stern’s blueprint proclaimed the dazzling possibilities of a hyperkinetic, multichannel universe. And though it was too late to restore the New Amsterdam for Beauty and the Beast, which was set to open at the Palace in April 1994, Disney’s interest was causing other entertainment corporations to take notice. Pearson PLC was already looking at One Times Square for Madame Tussaud’s. Now Viacom wanted to turn three theaters into an MTV studio complex, while AMC Entertainment, the Kansas City-based cinema chain, was readying a proposal for a $53 million, 6,000-seat multiplex just down the street from the New Amsterdam.

Then Disney and Tishman started talking about going in on a hotel-retail-entertainment development at the Eighth Avenue end of the block. The location, diagonally across from the bus terminal, was the diciest in the area. Undeterred, Stern took Eisner to the bus terminal at rush hour. “I think he expected to find ‘Ratso’ Rizzo on the front steps,” Stern recalls. Instead he saw thousands of office workers in business suits. The terminal wasn’t the problem—but if you didn’t deal with Eighth Avenue, 42nd Street would still be mired in sleaze.

If anchoring Eighth Avenue made sense from a defensive point of view, it also offered new business opportunities for Disney’s theme parks and resorts division, now approaching global saturation. “The draw of Walt Disney World and of Disneyland is so big that if we built a third billion-and-a-half-dollar theme park somewhere in the U.S., it would be like eating our young,” says Rummell. “So if you’re a public company and you’re committed to growth and you have an expertise in storytelling and placemaking, are there ways you can do that at less than a billion-dollar level?”

THIS QUESTION PRESUMABLY GAINED URGENCY as Disney ran into trouble launching new theme parks. Disneyland Paris finally eked out a $23 million profit (according to French accounting procedures, which are less stringent than their American counterparts) in fiscal 1995, but not before Disney reduced its stake from 49% to 39%. Then there was Disney’s America, which was supposed to go up in the Virginia hunt country—until it got ridden out of town by the Washington Post, with tar and feathers from the likes of William Styron, David McCullough, and James McPherson.

Disney officials deny that these debacles fed their appetite for smaller entertainment opportunities. “It’s got nothing to do with that at all,” Eisner insists. Nonetheless, Disney’s operating income from theme parks and resorts has grown less than fivefold since Eisner took over, while income from consumer products has increased almost ten times and filmed entertainment earnings have multiplied an astonishing 448 times. Little wonder, then, that Disney has been thinking differently.

Disney Cruise Lines is set to begin operations in Florida in 1998. The Disney Vacation Club, a time-share organization, is constructing units in places like Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, and Newport Beach, California. Disney Quest, a virtual-reality arcade experience, is soon to be announced. Complementing these ventures are Disney Theatrical, the engine that drove Disney to 42nd Street, and the Disney Stores, some 450 of which are now open around the globe.

“We are creating a series of products that are Disney-branded—smaller-than-a-theme-park products you can put on a 42nd Street anywhere in the world,” Rummell explains. On Chicago’s State Street, for example: Disney recently made a deal for the old Chicago Theater on that once grand thoroughfare, and it’s been in talks about other properties nearby. “There are probably other places—I’m not going to tell you where—that fit this same description,” says Rummell. “Places that were wonderful that aren’t wonderful anymore. But the question in these urban environments really becomes, Is there a way you can have enough control? Because we are control freaks.”

Control is what Disney got by joining Tishman on its bid to develop the Eighth Avenue end of 42nd Street. Disney was thinking about building a Vacation Club, and maybe putting a Disney Quest in the entertainment complex. But it wasn’t an equity partner, and it was making no commitments as a tenant. Essentially, Disney offered Tishman its name—a not inconsiderable resource—in exchange for a hand in shaping the proposal.

Will Disney turn 42nd Street into theme park? It’s had a touch of that from the start: Murray’s Roman Gardens, which opened in 1909, may well have been New York’s first themed restaurant.

Tishman was to pick the architect, subject to Disney’s approval. After some discussions with Frank Gehry, John L. Tishman, the company’s 70-year-old chairman, went with Arquitectonica, the Miami Beach firm whose jazzy modernism provided the visual signature for Miami Vice. The proposal they developed was structurally straightforward—a 45-story hotel tower rising behind a retail base—but it looked like a falling meteor, with a streak of light cleaving the tower in two as it headed for the Vacation Club (a box cantilevered over the base) and an explosion of “pixie dust.” Tishman figured it would be buildable; Eisner liked its impact—especially from the entrance to the New Amsterdam.

In the spring of 1994, with Beauty and the Beast breaking box-office records, Eisner announced that Disney Theatrical would launch a new show each year beginning in 1997—a surprise to the folks at Disney Theatrical. Yet in December, when Disney finally signed a 49-year lease for the New Amsterdam, the deal was still tentative: If two other major entertainment companies weren’t committed to the street by July 1995, Disney could walk. By then, MTV had also taken an option on the theaters across the street, and Madame Tussaud’s was eager to move into One Times Square—the tower where the ball drops on New Year’s Eve—for its interactive wax museum. But within weeks, those two deals and the AMC bid started to unravel.

In March 1995, with nearly two decades of planning and negotiations devolving into a game of chicken, Disney warned that time was running out. But Disney was also working behind the scenes, urging Tussaud’s to look elsewhere on 42nd Street, urging Tussaud’s developer Bruce Ratner to do a deal with AMC. Tishman won the competition for the hotel site—in large part, one of the losers later maintained, because of the Disney name, though by that time Disney was no longer billed as a partner in the development. (The company has since decided to focus on resort areas before trying urban time shares.) The last hurdle popped up when bids to renovate the New Amsterdam came in higher than expected, forcing a renegotiation of the deal.

The New York Times proclaimed the New Amsterdam “a vision of gorgeousness” when it opened in 1903. Photo courtesy H3

Hours before the July 15 deadline, everything fell into place—AMC, Madame Tussaud’s, the New Amsterdam. When MTV pulled out, Garth Drabinsky’s Livent, the company that put Show Boat on Broadway, swept in with a $22.5 million plan to combine two vintage theaters. “It was touch and go,” Imagineering’s David Malmuth says now, relaxing over lunch in the airy rotunda of the Team Disney building in Burbank, 2,500 miles away. “The thing that sustained us was the recollection of what it felt like walking into that space—how magical it would be to have that come back to life in a great opening night.”

June 24, 1996

June 24, 1996