“Red Sails: Explosion Event for the Groundbreaking Ceremony of Quanzhou Museum of Contemporary Art,” Quanzhou, China, 2024

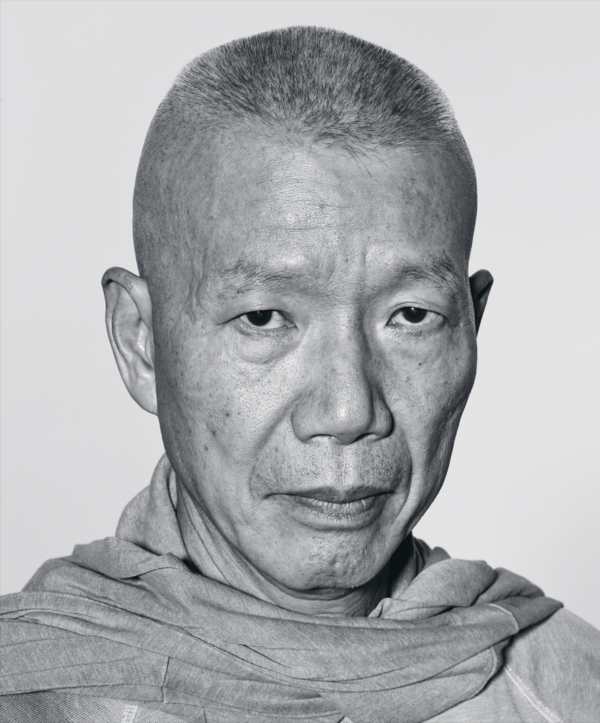

THE FIRST THING I NOTICED was the portrait of Mao. I’d just stepped into a large atelier in Cai Guo-Qiang’s New York studio, on the ground floor of a one-time schoolhouse in the East Village. I was expecting to see his signature multi-colored gunpowder paintings, not this. Something more like the three-meter-square canvas nearby, perhaps, showing animals engaged in highly unnatural couplings—an antelope mounting a leopard, a panda rogering a horse—as the world comes to an end in the background. So when Cai walked in a short while later, a tall, lean, ascetic figure wearing a simple gray work shirt and pants, with a faded orange scarf around his shoulders and orange sneakers on his feet, I asked him about the Mao.

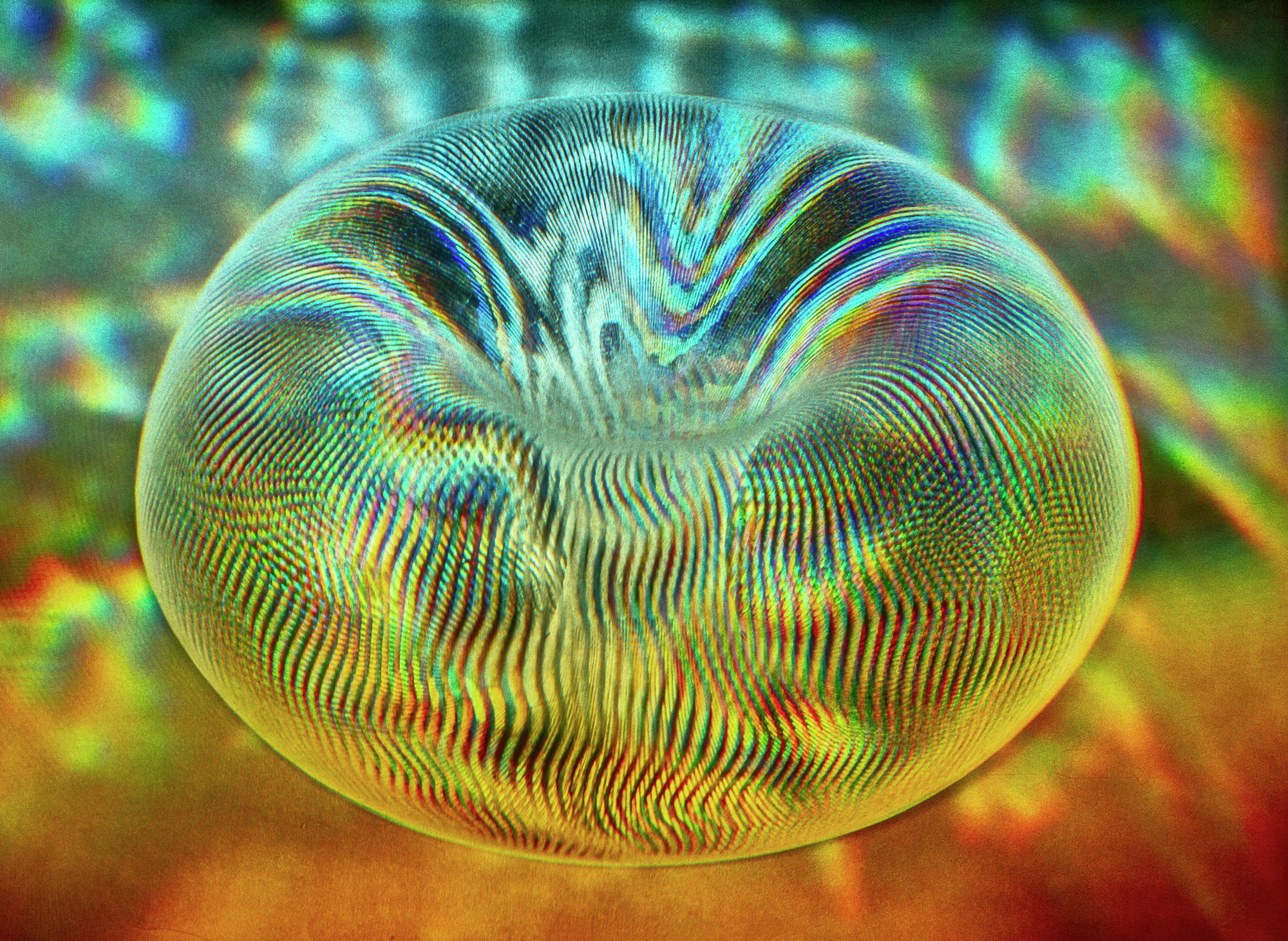

Blau International is available at Barnes & Noble bookstores in the US, at Classic Press Shops and LS Travel Network shops in Germany, and at select bookstores and art galleries worldwide. Cover image: “Study for the Cosmos No. 4,” 2022

Cai is of two minds about many things, but few more than Mao. Born in the ancient Chinese port city of Quanzhou in 1957, he was nine years old when China’s leader set the Cultural Revolution in motion. As a third grader, he helped hound his teacher out of the classroom, never to be seen again. Soon he was made head of a Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Team. Smash the windows! No more school! It felt liberating—until he found himself furtively burning books a few pages at a time with his father, a bookseller and collector who, in the ongoing purge of capitalists and intellectuals, was afraid of being branded a counter-revolutionary if he was caught with such things.

“Mao was a poet,” Cai said through a translator as we sat at a long, narrow table on one side of the room. “I grew up in his era, more or less influenced by his political belief in Marxism-Leninism, but at the same time by his grand and poetic vision. Because Mao advocated for revolution, fighting against authority, I was also”—or so he thought. In reality, he came to understand, Mao the revolutionary was also Mao the ultimate authority. “So this eventually became a rebellion against Mao,” Cai continued. “And using gunpowder was my way of breaking free from a society which was heavily controlled, very much repressed. It was my way of fighting back.”

Cai began experimenting with gunpowder in the early 1980s, when he was a student at the Shanghai Theatre Academy. By 1986, the year he turned 29, he was living in Tokyo and mixing gunpowder with paint. Over time he proceeded to the spectacular “explosion events” that made his name—thunderous apparitions that, when all went well, treated the daytime sky as a canvas for stupendously beautiful displays, appearing and disappearing within moments. Then, in 2015, he started making gunpowder “paintings,” controlled explosions in his studio using colored gunpowder on canvas or glass. The results have been gorgeous, even lush, yet strangely delicate, as if the implicit violence and extreme ephemerality of his explosion events were somehow transmuted into something more stable, more human-scaled, almost domesticated. Almost, but not quite.

“Using gunpowder was my way of breaking free from a society that was heavily controlled, very much repressed. It was my way of fighting back.”

Forty-two of these gunpowder paintings are currently in a solo show at White Cube Bermondsey in London. For Cai it’s a double first—the first time his work has been on view in the English capital since he staged one of his explosion events at Tate Modern in 2003, and the first time since he gained international recognition in the 1990s that his work has been shown in a major Western commercial gallery.

“Pink Poppy No. 2,” 2021. Gunpowder on canvas. 2 parts, each 72 x 60 in.

Mainly he has worked with institutions. He’s had a constant stream of commissions: the J. Paul Getty Trust, the Fondation Cartier, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Pushkin State Museum in Moscow, the Venice Biennale, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, the 2022 Olympic Games in Beijing… After a solo show at the Met in 2006 and a 2008 retrospective at the Guggenheim, he was besieged by gallerists as well. Jay Jopling, the founder of White Cube, a gallery closely associated with the Young British Artists of the ’90s, “first approached me in 2006, and he’s been pretty persistent. He told me we don’t have to have this official representation to work together—we can just do a one-time collaboration. So I wanted to just give it a try and see how it will go. I am also curious to find out, how will my works be received by these private collectors?”

“Poppy Series: Hallucination No. 3,” 2016-2025. Gunpowder on canvas. 3 parts, each 94 ½ x 59 in.

It’s not as if Cai hasn’t sold works before. In 2021, an NFT—his first—sold for $2.5 million in an online auction to benefit the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai. In 2013, a single-color gunpowder drawing mounted on an eight-panel screen sold at Christie’s for $2.4 million to benefit a new museum in his hometown of Quanzhou. (Unlike his gunpowder paintings, artworks in their own right, Cai’s gunpowder drawings are studies for his explosion events.) And in 2011, the same year she dropped a record-setting $250 million on a Cézanne, Sheika al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani bought seventeen works she had commissioned for a solo show at Mathaf: the Arab Museum of Modern Art in Qatar. Still, by standing aloof from the world of galleries and art fairs, Cai has been able to project a certain purity that’s rare in contemporary art circles.

“Sorry that we talked a lot about sales,” he said.

Cai Guo-Qiang. Photo: Richard Burbridge for Blau International

CAI GUO-QIANG MOVED to New York from Tokyo 30 years ago on a grant from the Asian Cultural Council, and for most of the years since he’s had his studio in this 1885 brick schoolhouse in the East Village. The place suits him. He acquired it from Maja Hoffmann, the Swiss pharmaceuticals heiress and arts patron, who bought the building in the mid-90s, when it was a semi-ruin surrounded by crack dens. The neighborhood has changed dramatically since then, and so has Cai’s space. In 2015, he brought in Shohei Shigematsu of OMA to redesign it. The ground-floor offices and ateliers are now pristine and white; rooms on the cellar level are divided by thick brick archways and lined with the ubiquitous gray schist that supports Manhattan’s skyscrapers. At the rear is a traditional Japanese tea room accessible by a nijiriguchi door—a feature said to encourage humility because it’s so low that to enter you have to crawl on your hands and knees.

Although the place is teeming with office workers, assistants, and interns, Cai spends most of his time, when he’s not traveling, some 40 miles away in the rolling hills of northern New Jersey. There, on a former horse farm, he lives in a sprawling glass-and-timber house designed by Frank Gehry and works in what used to be a stable. The Manhattan studio is mainly used for business meetings and, as it happens, interviews.

The cellar-level library at Cai Studio in Manhattan. Photo courtesy OMA

We discussed many things as we sat there—gunpowder, of course; Chairman Mao; Taoist philosophy and the importance of embracing change; his fascination with artificial intelligence. I asked him about what he calls “the unseen world”—a world that stands in opposition to the physical world, to the world our senses perceive, and that is clearly related to his belief in the mystical life force known as Qi, as well as to the highly counterintuitive, to Western minds at least, theories of quantum physics.

It’s as if the violence and extreme ephemerality of his explosion events were transmuted into something more stable, human-scaled, almost domesticated. Almost, but not quite.

His reply was oblique. “Since I was a child, I’ve been really afraid of death,” he said, “especially the death of my grandma.” He and his grandmother, Chen Aigan, were extremely close from his earliest childhood. Having renounced Christianity and embraced traditional Chinese deities, she gave him yellow paper amulets for protection and found a witch who would provide him with herbs when he was sick and explain why he’d fallen ill—because he’d gone fishing in a pond and been attacked by the ghost that lived there, for instance. But none of this made him any less fearful for his grandmother. “When I was just two or three years old, I would be very afraid that one day she would leave me. And my grandma told me, ‘Don’t worry about it. I will be with you for a long time. I will live to be 100 years old.’ And indeed, she lived until 100.”

“Sky Ladder,” Quangzhou, China, 2015

Then he started talking about what is almost certainly his most astonishing work to date. Sky Ladder was a wildly ambitious explosion event Cai spent 21 years trying to bring off. He finally succeeded on his fourth attempt, on a small island just off Quanzhou, a location he chose because his grandmother, who had never witnessed one of his events, would be able to see it. It involved an enormous, ladder-like construction that was rooted to the ground at one end but held aloft at the other by an enormous helium balloon, its top as high as a 125-story office building. The ladder was coated with yellow gunpowder, so when lit from the bottom at night it became a golden apparition climbing into the sky. The event took all of 250 seconds, but the sense of a life force ascending to the heavens was unmistakable. “Sky Ladder was my gift for my grandmother,” Cai said. “One month after I realized Sky Ladder, she passed away.”

He paused for a moment. “A lot of today’s conversation is me recalling my old memories,” he said. And then he proceeded to recall more.

“In childhood I liked to hide under my cover in bed and listen in secrecy to radio stations from foreign countries—the Voice of America, the radio station from the Soviet Union, or the radio from Taiwan, which was just across the strait from my hometown. At the time of the Cultural Revolution, if that kind of activity got discovered, the consequence was pretty dire. And then when I grew up, I started to do Projects for Extraterrestrials,” a long-running series of artworks that he imagined might start a dialogue with alien intelligences. “And now, when I’m developing my AI model, I think about AI evolving into this interspecies intelligence. So looking back, I think I have constantly been looking for a distant land, a distant destination that can be the unseen world or the other shore. And all of that has to do with uncertainty and chaos, which I find to be closely related to the essence of the universe. That feeling of anxiety and uneasiness as a child listening to foreign radio stations under my covers, and this uneasiness I had when using gunpowder and now using AI—these are all similar in a sense.”

Art Starsand the machinery behind them. |

Cai Guo-QiangAfter working with institutions of the highest rank, from the Getty to Tate Modern, one of the most recognizable artists of recent memory is dipping more than a toe into the commercial art world.

|

WangShuiObsessed with the origins of consciousness and humanity’s preoccupation with violence, WangShui hopes that, through AI, love will find a way.

|

A ‘Holopoem’ for the CosmosEduardo Kac found an unusual public space for his artwork — orbiting the sun.

|

Making Art Out of Bombshells and Memories in VietnamTuan Andrew Nguyen’s videos and sculptures uncover haunting artifacts and stories from the Vietnam War.

|

David Byrne Is Totally ConnectedThere’s a new gallery show of his whimsical drawings — and coming this summer, an immersive art-and-science experience.

|

A.I. Meets Fatherhood in an Artist’s New WorkIan Cheng’s latest: a narrative animation powered by a game engine and partly inspired by his two-year-old.

|

Frank Gehry’s Disney Hall Is TechnodreamingData artist Refik Anadol creates a swirling projection on steel for the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

|

Alan Vega Ignored the Art World. It Won’t Return the Favor.A year after his death, the lead singer of Suicide looms over the downtown art scene.

|

The Whitney After AllThe Whitney Museum never really fit in uptown. Now it has relocated to a part of the Village that until recently was a reeking abattoir. Home, sweet home.

|

A Palace of WondersThe Panza Collection mounts a show challenging perceptions.

|

Last LaughJay Gorney sells art that sends up collectors. “They hear tom-toms in the distance,” says a curator, “and they get out their checkbooks.”

|

Cool John B.John Baldessari got rid of all the extraneous stuff, like form and beauty. Now he’s the éminence grise of conceptualism, in the spotlight at last.

|

As the Art World TurnsThe mix of art, big bucks and hype has turned the art world into a soap opera. Which brings us to Julian Schnabel . . .

|

CAI WAS 57 WHEN he finally realized Sky Ladder. The year was 2015—the year OMA reinvented his East Village studio, the year he started making his brilliantly colored gunpowder paintings. And while he has continued to produce explosion events and gone on to experiment with new, digital technologies—virtual reality, NFTs, AI—these gunpowder paintings represent a significant shift. They show his continued fascination with gunpowder, and with all that it represents for him, but they also recall his youthful longing to be a painter.

Cai’s development as an artist began with his scrounging of paint and canvas, or of paint and canvas substitutes, as a penniless youth in Quanzhou and then in Shanghai. Soon he began to experiment, setting the paint on fire or using a fan or a hairdryer to blow it in different directions, but the results were unsatisfying. “I found both blowing wind and burning too controllable,” he explained, “in the sense that I could still very easily control how it was going.” Gunpowder appealed because it was much more difficult to manage. By 1984, he was mixing the powder with paint and setting his canvases alight.

He was well aware of the danger. A few years earlier, two of his cousins had stuffed some gunpowder into a small bottle and lit it with a homemade fuse. They were planning to throw it out the window to scare some other kids, but before they could do so it exploded in his younger cousin’s hand, blowing off three of his fingers and sending a shard of glass into his older cousin’s neck, leaving him dead. “But through gunpowder I found a way to let the unseen energy and accident guide my creative endeavors,” Cai said. “It’s in a sense like submitting myself to destiny. So in that process I have a dialogue with the unseen world and its energy.”

Eventually he did away with the paint and turned to gunpowder as his primary medium. His first explosion event, in 1989, lasted all of two seconds. He’d been thinking of returning to China from Japan, but the regime’s assault on anti-government protesters in Tiananmen Square that year made him think again. Instead he joined an outdoor art exhibition in suburban Tokyo, set up a yurt that resembled the tents the protesters had erected in Beijing, and exploded it with gunpowder. He called this Human Abode: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 1.

In a way it harkened back to his adolescent under-the-covers listening habits. “I think my pursuit of the radio stations of enemy countries, whether that’s the unseen world or the distant, other side of the world, was also a will to break free from control, free from confinement, free from my disappointment in reality.” But Cai is a wizard of paradox, a maestro of duality, and as he spoke it became increasingly clear what that means for him.

“When we are facing these setbacks, whether from the political situation or in our personal lives, we tend to pursue something that’s more distant or more permanent. I want to transcend reality, to reach a higher, spiritual dimension that is beyond the space-time of reality. But at the same time, I am confined by the reality I live in and I am inevitably influenced by that reality. So I am like a pendulum that is constantly oscillating between two ends.”

He paused for a moment to let his translator catch up. “As an artist, I have many goals that I want to realize. For example, when you are painting, you would need canvas, you would need fire, you need to ignite the canvas, and you need to make lots of controls.” (Obviously these are not all things other painters need, but Cai is not like other painters.) “I have this strong desire to accomplish these goals, which results in a sense of autocratic control. But at the same time, I yearn for this freedom. I yearn for this other-worldly miracle to happen to me, and then that is like democracy.” The question, then, is “how can we give our life a bigger freedom?”

Democracy and autocracy, freedom and control, gunpowder and paint: Ever since he was a child, Cai has been drawn to both. It was at this point in the interview that I realized, how could he not have a portrait of Mao in his studio? ◆

“When the Sky Blooms with Sakura,” Iwaki City, Japan, 2023

October 22, 2025

October 22, 2025